Once upon a time there was a myth of Main Street U.S.A. and Mayberry R.F.D., where Aunt May baked pies, Uncle Joe worked hard in the field, the endless grain stretched golden-brown as high as an elephant’s eye, and everyone was very, very white. When we think of who reinforced that trope among early 20th Century painters and illustrators, Norman Rockwell comes to mind, as does Andrew Wyeth. And Grant Wood. Very different artists, sensibilities, and geographies. But all invested in a certain halcyon Camelot-icization of our Manifest Destiny. If Rockwell was the most unctuously cornpone of the three and Wyeth the flintiest, then Wood was the archest, as anyone who has ever spent time with his unnerving iconic work “American Gothic” (1930) can attest.

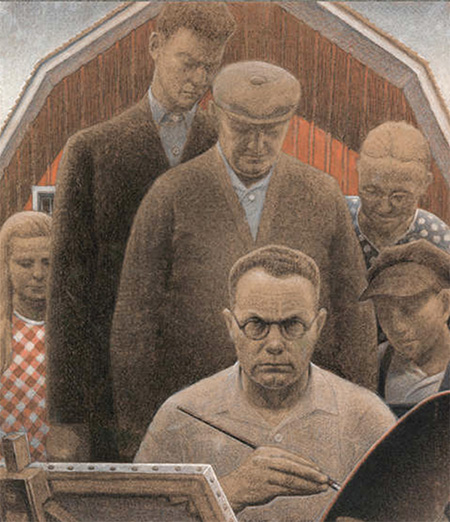

One of Wood’s specialties was embedding his work with double meanings, ambiguities, and symbolism which only initiates would recognize. Some of those encoded references are homoerotic. Wood’s closeted gayness was first explored in 2010 in biographer R. Tripp Evans’s groundbreaking “Grant Wood: A Life,” which essentially outed the artist and chronicled the difficulties of posing as a bastion of Midwestern values while concealing his sexual identity. Taking up where Evans left off, art historian Sue Taylor — longtime Portland correspondent for Art in America and professor emerita at Portland State University — has penned a deliciously titled monograph, “Grant Wood’s Secrets” (University of Delaware Press, 2020), a consideration of Wood’s challenging paintings vis- à-vis his queerness. It is an intense read, evincing deep scholarship and canny insight. Like a libidinal detective, a forensic homosexologist, she advances an ambitious series of close readings of the artist’s paintings, poring over his imagery for telltale signs of the homoerotic gaze. The result is a subtly but strongly argued case that Wood, while masquerading as an overalls-wearing exemplar of traditional agrarian values, was embedding in his imagery references to gay handkerchief codes, stylized penises, anal sex, masturbation, and the unspoken traditions of barnyard bestiality.

Essentially, he was sneaking camp and gay lust under the radar in his would-be paeans to wholesome Americana. Can we agree that there is something fabulous about that? An artist widely embraced as a proponent of piety, patriotism, and Protestant work ethic was in fact deconstructing those very tropes, and almost nobody noticed the ruse.

Taylor’s writings often have a Freudian bent, which she adopts with virtuosity and without apology. For this book, she received a grant from the American Psychoanalytic Association, which she used to retain psychoanalyst Gerald Fogel to help her consider Wood from a classic Freudian perspective. With an overarching compassion she illuminates the frustrations that stymied the artist and the sublimations that drove his creativity. In the Freudian model, his gayness seems to have arisen from the classic combination of a remote, absent father (who died when Wood was only ten) and overbearing mother.

He briefly escaped small-town life during four sojourns to Europe in his early to mid-30s. In Paris he grew a defiant, flaming red beard, and one imagines he must have positively eaten up the vie bohème — a chance for a committed but self-limited regionalist to moonlight as a cosmopolite. Wouldn’t he have been tempted to linger, for, as Sophie Tucker sang in a popular tune of the era, “How ya gonna keep ’em down on the farm/now that they’ve seen Paree?” But at his core Wood was a provincialist, and Iowa was in his blood. “I came back because I learned that French painting is very fine for French people and not necessarily for us,” he told The New York Herald Tribune. “I realized that all the really good ideas I’d ever had came to me while I was milking a cow. So I went back to Iowa.” Which rings a little glib and defensive.

One of his conflicts was that he was the perennial good boy; as a good son, he needed to hurry back to his mother and the native sod he hocked in his ongoing Iowa boosterism campaign. There is a churlishness beneath all that cow-milking rube-talk, which seems to have stemmed from a love-hate relationship with the rolling hills and planted fields, church socials and green-bean casseroles in the fellowship hall, lace doilies and pursed lips and staring at the farmhand a little too long. I sense he resented that his painterly fame was so closely tied to his small-town habitat, which he bitterly pilloried in his revenge fantasy, “Daughters of Revolution” (1932), a triple portrait of smugly sneering thin-lipped biddies, which Taylor finds misogynist and mean-spirited.

Wherever one looks in Wood’s oeuvre one often finds tokens of queerness stealthily implanted. He does not render townscapes, big-sky vistas and loamy soil with any seething organicism, but rather with a kind of foppish Noël Coward urbanity, which feels incongruous. “Fall Plowing” (1931), with its meticulous rows of nipple-shaped hay lined up with discrete shadows, is a paragon of epicene anal-retentiveness. Its “meticulously tidy brushwork,” Taylor observes, harbors a fussy, “almost hallucinatory verism.” The trees in “Young Corn’ (1931) are just too prissy, puffy, and perfect — a landscape of the effete. Under the rubric of hard work and red-blooded masculinity, Wood finds occasions to exalt fetching farmboys, as in “Study for Breaking the Praerie” (1935-39), shirtless soldiers (“Soldier in the War of 1812,” 1927), and many a pair of tight trousers stuffed with muscular glutes tensed for the plow (“Spring in Town,” 1941). There are parched field workers suggestively pressing jugs to full lips, desperate for surging infusions of replenishing fluids (“Plowing on Sunday,” 1934). Then there is the unabashed outdoor-bathing fantasia of “Sultry Night” (1938), whose full-frontal male nudity caused such a scandal that Wood ultimately destroyed the painting in a fit of pique. It is tragic that his most straightforward celebration of the nude male form — perhaps the closest he ever came to declaring his sexuality — became an albatross.

It would be too easy for us in the present to look askance at Wood’s passing for straight, but Taylor reminds us of of the era’s draconian persecution of those the law deemed “moral or sexual perverts,” subject to punishments including forced surgical removal of the testes. Taylor also details the smear campaign against Wood in the early 1940s, instigated by his department chair, Lester Longman, at the University of Iowa. Although Longman’s attempts to question Wood’s sexuality and impugn his moral and aesthetic credibility did not succeed in getting him fired, the whole affair took a toll on the artist’s mental health, which was already compromised by heavy drinking.

One key to understanding Wood’s sexuality is a biographical document, entitled “Return from Bohemia,” published for the first time in its totality in this book. Although it is not known how much, if any, of this narrative was written by Wood himself and how much by his assistant and likely lover, Park Rinard, it is nevertheless a valuable window into the artist’s formative years. (It was to have been part of a larger book for Doubleday, explicating Wood’s views on regionalist art; however, the book was never finished.) Recollections of his childhood are rich with psychosexual symbolism, with garter snakes, crowing cocks, gopher holes, and rams standing in for genitals and sex acts. As a literary project, “Return from Bohemia” is unremarkable, but as a psychological Rosetta Stone it is quite valuable.

Reclaiming Wood as a queer artist would be a difficult proposition, but it is not Taylor’s goal. Her modus operandi is simply to consider the artist from the viewpoint of queer studies and postmodern attitudes about gender and masculinity. One can read hypocrisy into Wood’s wardrobe-department pantomime of homespun values and the pains he took to conceal his homosexuality, but it’s also possible to look at him as a sophisticated trickster, subverting the system from within, planting wickedly coded wit and saucy gay symbols in plain sight, planting transgressive ideas beneath the veneer of red-blooded, ham-handed patriotism. I think he really did love the Iowa landscape and aspects of rural life but felt hemmed in by the limits of regionalism. His milieu was also his trap. That must have driven some of the passive aggression we see in his work, particularly in his portrayal of women, as well as the cleverness and invention with which he dropped sexual clues within his pastorales. Taylor gives us much to ponder in this thoughtful study. Troubled, conflicted, possibly self-loathing, Wood lived halfway between truth and falsity; his work’s ambiguity simultaneously bolstered and undermined the ideal of the American Midwest.

“Grant Wood’s Secrets” is available at:

https://www.amazon.com/Grant-Woods-Secrets-Sue-Taylor/dp/1644531658