Most of us have at least one word or phrase that we hate — a word that rankles, that grates in such a way that we cringe. The language of and around contemporary art offers an ample assortment of “I hate that word” candidates. For me, that word is what I often refer to as ‘the P-word,’ aka “practice,” most notoriously as in, “my art practice.” Back in the day, I was oblivious to the word, and then one day, I heard it in an artist’s studio, and from there the usage seemed ubiquitous. And eventually, ever so gradually, I began mounting my counter-attack.

I’m not alone in my annoyance with the P-word: no less than Roberta Smith and Peter Schjeldahl — both living legendary art critics — have expressed their disdain for the word. Smith in a New York Times piece, “What We Talk About When We Talk About Art,” from December, 2007. Schjeldahl more recently, in “Get with It,” his New Yorker review of the 2014 Whitney Biennial. While I fully appreciate their respective analyses of the P-word — she on its oversimplifying and sanitizing qualities, he on its roots in fashionable academic critical theory, and both of them on its implicitly flawed air of professionalism – my own aversion to the word has always been more visceral; even anti-intellectual.

The worst aspect of the P-word for me is its aura of self-seriousness. As the pandemic has put art into a wider perspective, some will argue that having art in our lives is as important as ever. But I think those arguments miss the boat. What about rent (or, for those a bit more privileged, a mortgage)? What about food? That visceral part of my reaction to the P-word has something to do with my bristling at the inflated values that some implicitly invest in art, based on the signifiers embedded in “my art P-word.” Now, to be fair, I’ve encountered people who use the word yet have great senses of humor, and people who hate the word but have no sense of humor. But ultimately, I’ll put my money on those who frequently put the P-word into P-word (do you follow me?) as suffering from too much self-seriousness. What’s my proof? Honestly, I’d be hard-pressed to offer any; it’s just one of those things, like ‘truthiness,’ where you don’t know it for a fact. You just know it’s true.

To support my fledgling anti-P-word campaign, I started by banning guests from using the word on my podcast, “The Conversation.” It’s in the show’s guidelines. As you might imagine, that hasn’t always work out wonderfully. Many guests found it funny; others tolerated it; a few pushed back, and one big-name artist, a confirmed guest, upon reading the rule in the guest guidelines, decided not to come on the show at all (I later learned they had a specific objection to “telling people what they could or couldn’t say”). I’ve since substantially loosened the terms to be merely a suggestion, as in “we would appreciate it if you’re mindful of your use of the word (preferably refraining from use).” This may seem pretty pedantic, but it occasionally plants a seed, and some are even sympathetic to the cause.

And, just so you know the various rationales of the P-word, here are the most common:

• It encompasses the full scope of one’s artistic production (from making objects to maintaining routines to performance to writing);

•. It equates to and signals one’s professionalism as practitioners, akin to someone’s dental practice, their law practice or their chiropractic practice (among many others);

•. It represents one’s ongoing, ritualistic commitment to whatever it is you do, including experimentation, struggles, failures, habits and routines, as in a yoga practice or athletic practice. As one past guest asked: “has anyone ever talked about ‘practice’ not as in a Legal Practice sense, but in the Buddhist sense of always trying and never achieving? That’s sorta how I think about it.”

That question poses a rather beautiful sentiment. Still, I don’t believe many artists, especially those who frequently refer to their P-word, work that way. This again is my intuitive sense — I don’t know it for a fact, but I know that it’s true — hence my earlier point of having anti-intellectual tendencies. I think the P-word, as Schjeldahl conveyed in “Get with It,” is a way for these artists to finesse their “sense of discrete, professional enterprise.”

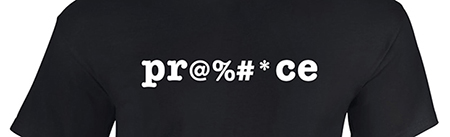

Four years ago, Patrick Camuti, an artist and art teacher based in the Pittsburgh area, reached out to me with a proposal. That proposal led to a limited edition of P-word t-shirts, or, more specifically, “pr@%#*ce” t-shirts. Several listeners bought them in one of the available black, blue, or blue heather colors. They are now either wearing them around the house, or out in the world, and likely receiving some very quizzical looks when they do.