The Getty Foundation recently announced the third iteration of its ongoing series of collaborations with Southern California arts institutions, known as Pacific Standard Time (PST). Arriving in 2024, it will be devoted to presenting work that explores relationships between art and science. Participating venues considering artists who fit the bill and deserve wider recognition should reserve a prominent place for San Diego-based Kelsey Brookes, a former microbiologist who once worked as a researcher for the Centers for Disease Control.

Brookes abandoned his career as a scientist in 2005 and, a few years later, he was producing and exhibiting figurative paintings influenced by his practice of various forms of meditation. In 2012, he shifted to a new vocabulary of allover marbleized patterning, with some early examples still tied to the figurative work. His abstract “Padmasana” paintings, for example, are shaped like the lotus position the body assumes when practicing yoga. For the majority of his recent works, however, Brookes found his true voice by introducing a science-based system for making visually charged paintings. In the tradition of conceptual mainstay Sol LeWitt, who pioneered systemic art in the 1960s, Brookes now makes art based on self-imposed rules, and the results are outstanding.

Like the 1960s paintings of Richard Anuszkiewicz or the 1980s works of Alex Grey, Brookes’ compositions are filled with radiant colorful patterns that mix optically to result in uplifting and transcendent experiences. And like Fred Tomaselli, Brookes believes that viewing dazzling patterns associated with the experience of drugs can provide a drug-free trippy experience. Whereas Tomaselli constructs compositions by making patterns from actual pills and cannabis leaves, Brookes creates imagery that derives from a drug’s molecular structure.

In selecting the molecular diagrams upon which to base his paintings, Brookes opts to represent substances that can promote happiness, well being, and spiritual states, such as serotonin and LSD. To begin a painting in this series, he plots out a diagram at the center of a composition, marking the location of each atom with a dot. He then paints ribbon-like concentric rings around the dots, moving outward. He repeats the procedure until a canvas is completely filled, varying his colors along the way. In paintings such as “Serotonin” and “LSD”, the rippling optical energy that animates each work effectively simulates what Brookes considers to be the brain wave activity produced by psychoactive drugs, as well as the psychedelic patterns that might enter one’s visual consciousness.

Around 2015, Brookes moved from chemistry to mathematics for his point of departure for determining the structure of his paintings. Specifically, he began utilizing a numerical sequence and an ideal proportion which have fascinated artists for centuries, from Leonardo da Vinci to Jacques Villon to Mario Merz. The progression of numbers known as the Fibonacci Series can be found in various aspects of nature, including the growth of plants and the reproduction rate of rabbits. Mathematically speaking, the sequence is an additive one, where the first two numbers, when added, equal the third number, and so on ad infinitum (i.e. 1 + 2 = 3, 2 + 3 = 5, 3 + 5 = 8, etc.). Closely related to the sequence is the ideal ratio known as the Golden Section or Golden Mean. In Greek, it is the equivalent of ‘π’ and computes to 1.618.

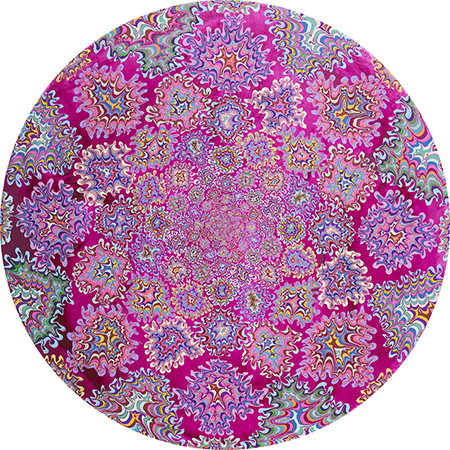

To create a painting based on the Golden Section, Brookes begins by drawing a circle at a composition’s center, and then surrounds it with rings of new circles that increase in diameter incrementally at the ratio of 1.62 (1.618 rounded up). He then paints the marbleized patterns within and without each circle until the entire surface is filled. In the tondo painting “Mean Ratio, 2 x, 24 in., No. 1,” (2015), every section is proportional to every other section using a mathematical system that was long regarded as divine, while the emphasis on magenta as the dominant color produces a richly textured effect that suggests a plush Persian carpet. In a related series of multiple-panel paintings, the “Fibonacci Series” is more readily identifiable, as separate proportionately related panels are stacked vertically, each being 1.62 times larger than its neighbor in the grouping. Brookes has also made a number of totemic sculptures that recall Constantin Brancusi’s “Endless Column,” but are based on undulating wave forms that he reshapes using the ideal proportion. These too are made all the more vibrant by having been painted with Brookes’ familiar patterning.

In his latest series, Brookes cuts apart actual Indian tapestries and sews the pieces together to form abstractions that simulate the approximate molecular shapes of psychedelic drugs such as serotonin, LSD, and psilocin, which the body produces upon ingesting psilocybin (aka magic mushrooms). In so doing, he performs an aesthetically effective synthesis of the geometries of traditional sacred mandalas with mathematically measured structures of substances known to produce heightened spiritual awareness. Like the mandalas that inspire them, Brookes’ tapestry works can be used as vehicles for meditative contemplation, but with the added benefit of being enhanced by an optics that stimulate happiness.