Continuing through September 6, 2021

Bisa Butler calls them Kool-Aid colors. She’s speaking of her bright palette, not a tray of paint but a wonderland of cloth — shelves and bolts and snippets and swaths of it, solids and patterns, in intense hues inspired by African textiles, also industrial-sized spools of colored thread. From these materials, she renders larger-than-life portraits of Black Americans.

An exhibition of 22 of Butler’s quilted portraits opened at The Art Institute of Chicago February 11, the same day the museum reopened after nearly a year of being mostly closed. Butler’s vibrant work sounded a loud and welcome wake-up call at the top of the museum’s Grand Staircase, after the city’s, and the nation’s, collective art hiatus. You could almost hear the color. Light poured in. Everything seemed possible again and some things seemed possible for the first time, and not just art. (Note to Chicago museum goers: There’s also a sprawling, dimly lit Monet show at the other end of the museum, in Regenstein Hall, for those who prefer a more sedate and differently beautiful reentry to this brave new world.)

From the start, Butler’s commitment to color was a given, a mandate passed down by her AfriCOBRA-affilliated art professors at Howard University in the 1990s who forbade their students to dilute their colors with white. Working in textiles, though, was a compromise, at least initially. Butler had always sewn as a girl, along with her mother and grandmother, but she only started working with fabric as an art medium in graduate school when she became pregnant and couldn’t tolerate the smell of paint anymore. She never went back.

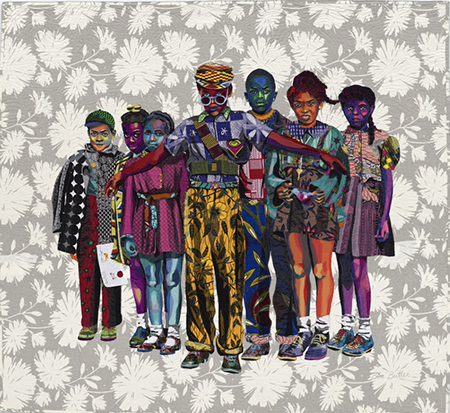

Butler works from photographs, breaking up two-dimensional images into smaller shapes suggested by the anatomical structure, draped folds of clothing and tonal values of her subjects. She then enlarges these shapes to scale, cutting fabric and assembling it piece by piece, layering and collaging it and using an industrial-sized sewing machine to stitch it all together. Some pieces are tiny. A highlight on the edge of a nose can be a single scrap. The assembled figures are then sewn onto backdrops made from patterned African textiles, some from Ghana, her father’s homeland. The completed wall hangings, all made slightly puffy through the quilting process, can take hundreds of hours to complete.

The process is important. It’s linked to her heritage, her mother and her grandmother and before that her ancestors. Quilts are rooted in the African American past, a domestic art form made almost exclusively by women in that composite of necessity and aesthetic impulse that drives so many art forms formerly known as craft. As for Butler’s subjects, all African American, these are not struggling people. The people in the photos she works from may have, likely did, struggle and suffer, but that’s not Butler’s focus. Her portraits show people who are proud, strong, complex, dignified, self-contained and, above all, beautiful. Beauty can be a throwaway word when it’s used to describe art but for Butler it’s a conscious aim. Beauty here works on a visceral level. The quilts are simply delicious, exhilarating to look at.

A glimpse online of some of the sepia toned 19th- and early 20th-century photos Butler used as reference doesn’t predict her joyous treatment. The source material is very sober indeed. These are no-nonsense people, posing with the usual stiff posture and long-held expressions necessary to early photography. Even her contemporary subjects, including children rendered in circus hues, hold our gaze with measured reserve. It’s what she does with the clothes that transforms them into a jubilation of pattern and color.

Some of Butler’s best quilts pay homage to familiar historical figures, Frederick Douglass for instance. But her most interesting works are inspired by found photos of people lost to history: families, groups of kids, a mother with her son. Rather than calling up official biographies, these works allow us to imagine lives, private narratives, secrets, dreams. Wisely, she doesn’t attempt to tell us their stories. Instead, she gives us the whole irreducible human enigma, wrapped in fabulous color.

Regarding her intentions, Butler says this: “I’m interested in saying, look what we can do.”

There’s a playfulness to this show that vies with its seriousness. I think it’s the clothes. Maybe we’ve all just been cooped up too long, but I caught myself, more than once, walking through this show thinking, I want those pants! I badly hope some museum gift shop product developer gets the go-ahead to turn a few details from Butler’s quilts into garments available for purchase.

Last but not least, a lagniappe: Butler’s DJ husband supplies a great playlist, one classic song to go with each quilt. It’s the best of the best — Etta James, Muddy Waters, Aretha Franklin, Mahalia Jackson, Michael Jackson, Sly and the Family Stone. You can listen there or, if great music distracts you from the visual by providing too much of a story line, look it up and listen. It will conjure up those colors long after you return home.