“Dreaming Forms: The Art of Leo Kenney,” Cascadia Art Museum, Edmonds, WA, through May 23, 2021

“The Lavender Palette: Gay Culture and the Art of Washington State,” Cascadia Art Museum, Edmonds, WA, October 24, 2019-March 15, 2020.

“The Lavender Palette: Gay Culture and the Art of Washington State,” Edmonds, WA: Cascadia Art Museum, 2020, 264 pp. $39.95, http://www.cascadiaartmuseum.org/museum-store/

Although the pathbreaking exhibition, “The Lavender Palette: Gay Culture and Art in Washington State,” closed after being extended last spring, the accompanying hardbound catalogue was not ready until recently. The exhibit was revelatory and beautiful, if too crowded for my comfort, but the book will last longer, the result of author David F. Martin’s 30 years of research since his arrival in Seattle in 1986, when he opened Martin/Zambito Gallery. Specializing in obscure regional artists, he uncovered tons of material by gay artists, most of whom he had never heard of. In the process of studying them, he has confirmed my contention in a 1981 article in “Art Criticism,” a quarterly journal from SUNY Stony Brook, NY, that underlying the so-called Big Four (Mark Tobey, Morris Graves, Guy Irving Anderson and Kenneth Callahan) was a persistent male figuration which was only downplayed with the rise of modernist abstraction both in Seattle and in New York, where many of Martin’s discoveries as well as the Big Four showed. I displaced Callahan (who may have been bisexual) with Leo Kenney, a self-taught artist, a was Graves. From my critical perspective, also like Graves, Kenney regularly used erotic symbolism as a coding for fellow gays and interested parties.

Later gay artists, except for Kenney (who died in 2001), are not mentioned. Martin follows his chapter with David L. Chapman’s illuminating essay on gay photography in the state, another landmark of scholarship, and 12 extensive biographical sections that include diaries, correspondence and journals of great interest.

Literally no stone went unturned in Martin’s copious hunt, not only drawing to our attention talented male and female artists such as Del McBride, Raymond Hill, Ward Corley, Malcolm Roberts and Sarah Spurgeon, but also finding illustrators, textile artists, potters and designers, all of whom he reverently rescues from purported neglect. But were they neglected because they were gay, or because they were not that good? There is neither a whiff of critical judgment in Martin’s comments nor any sign of current, postmodern critical theory, both of which might have put into better relief the questions of value, discrimination and group behavior. Instead, we gain a sensitive, sympathetic and amusingly salacious reading of artists of the early 20th century who were active in art schools, high schools, universities and small businesses, but who predated the contemporary art scene in Seattle — the state’s preeminent cultural center — by 50 years in some cases.

Among the 13 artists Martin spotlights, including six same-sex long-term partnerships and one male-female “mariage blanc,” several others mentioned, like Hill, Roberts and Kenney, were not at all ignored, but fell into relative oblivion after their deaths.

This is not strictly true of Kenney, the subject of the new retrospective following a bigger, more definitive exhibition in 2000 at the Museum of Northwest Art in La Conner, Skagit County. That survey, unlike Martin’s, borrowed Seattle Art Museum (SAM) holdings such as “Third Offering,” “Northern Image: Muse III,” (both 1948) and his masterpiece, “Inception of Magic,” (1945) all of which cement Kenney’s stature as a superb regional Surrealist. Martin leans instead on related collections of a local auctioneer and Kenney’s estate attorney. Thanks to the latter, incunabula of sorts replace established core art-historical works. Invaluable personal articles, such as letters and candid photos, are to be seen in display cases that substitute for a proper catalogue documenting the heretofore unseen paintings and the significant posthumous papers. For example, fellow artist and friend Richard Gilkey confesses in a 1947 letter to Kenney, “Your message arrived at the perfect time ... Believe me when I say that if it were not for friendship of this kind I could not go on.” Fifty years later, Gilkey committed suicide in Wyoming.

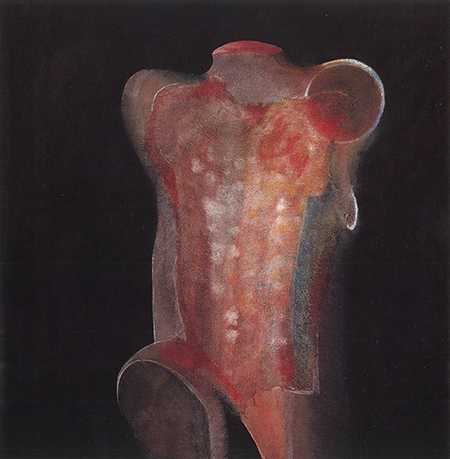

The strongest case that might have been made for Kenney’s rehabilitation is thus impaired without the establishment imprimatur of SAM. Even with the SAM holdings and the related works Martin has uncovered, Kenney’s early work, strong as it is in its own right, is guilty of woefully derivative 1930s Surrealism — Dalí, Tanguy, et al. The only “mystic” or mysterious part is the veiled homoerotic symbolism: transvestitism and flaccid penises.

After stints working as a window dresser at Gump’s in San Francisco, Kenney returned to Seattle and was awarded a SAM show on the basis of the artworks inspired by Gump’s Asian art inventory. In them Kenney evoked a sense of secret fraternities among ambiguously gendered priests and priestesses pointing toward closeted rituals, a sensibility already present in Tobey’s “Baha’i” paintings of the prior decade.

By the mid-1950s and 1960s, Kenney found a more colorful voice, this time based on Graves’ urn still-lifes of the late 1930s and early 1940s. Kenney’s “Dark Garden” (1954) makes decorative the sober religiosity of his older cohort. Seething colors emerge out of murky tide-flat browns and blacks. The final “Geometrics” fail as abstract art — a desperate attempt to modernize — but succeed as ornamental pendants for the hushed interiors of his supporters and closest friends.

Kenney’s sincerity and spiritual journeys (including mescaline) seem distant today, so internalized as to be anti-social, so submerged with sexual symbolism, cowering with desire. As times have changed for gays, so have the criteria, art-historical and otherwise, for elevating or dismissing such figures of the not-so-recent past.