A scaffold is a grid to build a dream on, a buttress between the envisioned and the executed. It’s a promise toward the progression of a plan. All of us now are staring up at a kind of scaffold: an infrastructure built by federal and state governments to construct a new, post-COVID reality. It is especially true for the artists, musicians, actors, and so many others in the creative/performing arts, as well as in the entertainment and hospitality industries, who saw their scheduled projects and very livelihoods evaporate as the public agora emptied. Hope itself is the scaffold upon which we are hanging our collective dreams of restoration, even as we suspect things will never be quite the same. How apropos, then, that Portland-based artist Avantika Bawa has turned her own COVID-dashed plans into opportunities for new aesthetic explorations, using the scaffold as her visual motif. (She has been depicting scaffolds in her sculpture and drawings since 2012.)

At the start of 2020, Bawa was deep into planning an installation that was to have opened last winter at The Sculpture Park at Madhavendra Palace in Jaipur, India. Its centerpiece was to have been a large-scale scaffold on the palace’s roof. She was expecting to work with artist/dealer/curator Peter Nagy, whom she’d collaborated before in the late 1990s and early 2000s. But summertime brought word that the show wasn’t going to happen. Plucky and indefatigable, which is to say constructively stubborn and defiant, Bawa determined to turn the proverbial lemons into lemonade. Effectively trapped in Portland due to travel restrictions, she decided she could still make a scaffold-based installation; she would just do in miniature. It didn’t take long for Jamie Wilson, founder of the new-ish Agenda Gallery, to invite her to exhibit these new works (all completed 2020-2021) in the gallery’s adventurously programmed shared-use space in southeast Portland.

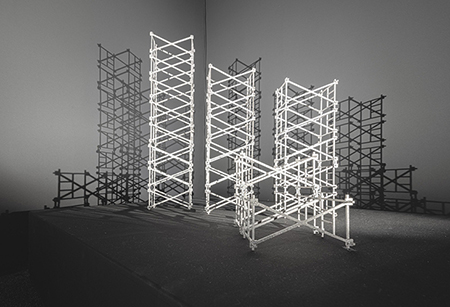

When she got to work conceptualizing the show, Bawa parlayed the necessity of downsizing into an opportunity to explore new materials and processes. For the first time she worked with 3D printers, fabricating maquette-like structures in nickel-plated steel with the aid of her colleague Noah Matteucci. These structures are clustered together, dramatically lit in a dark room, casting webs of interlacing geometric shadows on the walls. A sound element hums and hisses from hidden speakers, playing an altered recording of the 3D printers as they created the sculptures, as well as construction noise from the erection of the artist’s past scaffold projects in the U.S. and India. It’s an obvious but respectful paraphrase of Robert Morris’ “Box with the Sound of its Own Making” (1961). Beholding the structures and sound is an intimate, immersive viewing experience, with only one person or couple at a time allowed to enter the darkened sanctum. Gazing down at the crisscrossing, Tinkertoy-like grids (all titled after the overreaching rubric “Scaffold Configuration”) one becomes Gulliver in Lilliput, hyperaware of one’s disproportionate size in an unrecognizable world. It’s an invigorating disorientation, recalibrating our notions of architecture and self.

On a roll, enlivened by the pursuit of the new, the artist furthered her foray with a suite of monoprints in yet another form she’d never before endeavored: embossings on paper. (Technically, they are an integration of “ghost prints” and “blind embossings.”) Working at the photopolymer printing facility at Washington State University, where she is an associate professor of fine art, she composed subtly minimalist depictions of the building blocks of scaffolds. Decontextualized from the real world of blueprints, engineering and construction, these immaculately reductivist études, all on Magnani Pescia and BFK-Rives printmaking papers, recall East Asian pictograms in their jaunty contours and asymmetry. These insouciant, diminutive works have caught the attention of curator Stuart Horodner, who directs the University of Kentucky Museum. Horodner, who was curator at the Portland Institute for Contemporary Art in the early 2000s, invited Bawa to participate in a two-person show at the museum, coming up this fall, alongside sculptor/printmaker May Tveit.

Who could have predicted these fortuitous turns of events in an artist’s creative process and career trajectory, predicated on her adaptations to a worldwide lockdown? There are many integral paths artists have taken as a consequence of COVID, from monastic retreat to hyper-engagement with digital experimentation and collaboration. Who can say which strategies were better or worse in dealing with these unprecedented challenges? Every coping strategy is as unique as the individual who deploys it. Bawa’s approach stands out for its unapologetic pragmatism. After all, “Constructing Darkness” is not about COVID, although that is its raison d’être. Ruthlessly formalist, it is not a response to current events. Yet the repercussions of these events stretched the artist’s ambitions, in the process expanding her arsenal of materials and helping net her another exhibition. Maybe this is the overriding takeaway from this thoughtful and elegant exhibition: If you’re blocked from crossing the pass, make your way back down the mountain and then go around the base. Maybe the route not taken initially will offer vistas even more expansive than those we might have seen from the summit.