Continuing through August 11, 2021

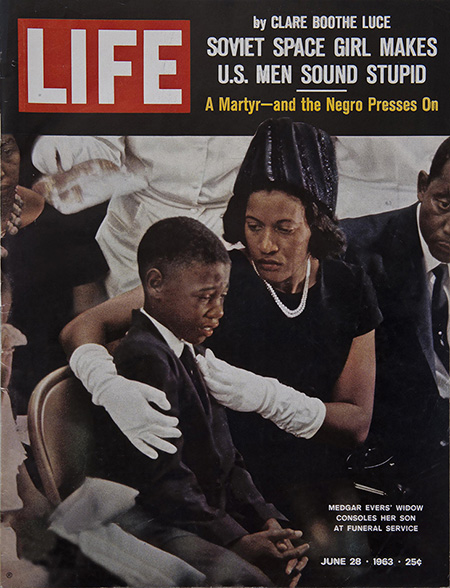

Decades before “Black Lives Matter” became part of our vernacular, visionary civil rights leaders employed images in advertising, film, magazines including “Life,” “Jet” and “Ebony,” newspapers, TV and many photographs, to alert the world of the distressing plight of many Black Americans.

As Reverend Martin Luther King, Jr. said, “The world seldom believes the horror stories of history until they are documented via the mass media.” This 1961 citation is one of many quotes in the exhibition, “For All the World to See: Visual Culture and the Struggle for Civil Rights.” Yet King was not the first to recognize the significance of visuals to shock “Americans, both black and white, out of a state of denial or complacency,” according to the show’s wall didactics.

That distinction belongs to Mamie Till Bradley, mother of 14-year-of Emmett Till, murdered in 1955 in Mississippi by white supremacists. In fact, this exhibition, organized by the National Endowment for the Humanities, describes in one poignant installation that Bradley “distributed to newspapers and magazines a gruesome black-and-white photograph of his mutilated corpse.” Yet after mainstream media rejected the picture, the grieving mother proclaimed, “Let the world see what I’ve seen.” Soon after, African American periodicals published her striking example of racism and brutality. It helped to jump start the Civil Rights movement. As the show explains, photos “transformed the modern Civil Rights Movement, impelling a new generation of activists to join the cause.”

“For All the World to See,” described by its organizers as “the first comprehensive examination of visual culture’s role in the civil rights movement,” was curated by the late Dr. Maurice Berger of the University of Maryland, Baltimore, and co-organized by the National Museum of African American History and Culture. After opening in 2011 at the International Center of Photography, New York, it traveled to several venues including the Smithsonian Institution. An abridged version of the exhibition, organized by the “NEH on the Road Initiative,” has subsequently traveled to dozens of venues, including this small museum dedicated to provocative exhibits.

The exhibition is divided into five sections: 1) “The Dawn of Civil Rights: Clowns, Servants, and Invisible Men,” exploring the power of images to perpetuate stereotypes and prejudice; 2) “The Culture of Positive Images,” on the importance of images to create black pride and accomplishments and to improve the negative view of African Americans; 3) “Let The World See What I’ve Seen: Evidence and Persuasion,” documenting violent acts against black people, including the Emmett Till incident; 4) “Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner: Broadcasting Race,” on the role of black performers while exploring controversial racial issues; and 5) “In Our Lives We Are Whole: Rethinking Blackness,” investigating the daily lives of Black Americans through snapshots and the role of the Black Panther Party, “in emboldening black pride, maintaining the status quo, or countering mainstream values and points of view,” as described in one installation.

Highlights of this multimedia exhibition include a 1968 CBS News documentary on photographer/filmmaker Gordon Parks; baseball cards featuring Jackie Robinson, Willie Mays and Hank Aaron; the history of black magazines; the 10th edition of Ralph Ellison’s groundbreaking book, “Invisible Man;” film clips from the 1963 Civil Rights March on Washington, D.C.; Muhammad Ali, then known as Cassius Clay, on the cover of “Time,” 1963; along with many more thought-provoking images, installations and objects.

Alongside these images, several disparaging visuals and objects include a film still from “Beulah,” a 1952 TV Show, presenting a negative view of black housekeeper; a 1950s plastic Aunt Jemima syrup dispenser; a Black Barbie; and a photo of a “Young black girl with white doll.”

“There have been claims that pictures matter, that images matter, that they can make a difference,” curator Berger said in 2011. “‘For All the World to See’ is living proof in so many ways that pictures — even things as ordinary as a snapshot — can truly change the way people understand issues and ideas in the United States and in the world.”

Indeed, this remarkable exhibition, curated and mounted more than 10 years ago, documents the profound impact that proactive images have on prevailing ideas about race. Yet as recent protests have demonstrated, our country today is more divided than ever.