I spent the month of June in my state of origin, Florida. It was the first time I’d been on an airplane in a year and a half, and the same amount of time since I’d seen my parents and brother. I was adamant I wasn’t going to travel until I got vaccinated, so as soon as the waiting period passed after my second dose of Pfizer, I jumped on the plane and headed back to my roots.

Before I left, a lot of friends here in the Pacific Northwest said things to me like, “Be careful down there,” and “Watch out for those Trumpers!” These admonishments were uttered with a wink but also with the air of superiority a lot of Left Coasters reflexively adopt when they discuss the American South. I’m used to this by now. Just as I listen to my Florida friends lecturing me by phone about how dangerous and lawless Portland has become, so I listen to my Oregon friends insisting how dangerous and backward Florida is. We love to demonize by region. Yes, I know that Portland can come across as precious and sanctimonious to other parts of the country. I also understand why the South gets beaten up. As one who’s lived not only in Florida but also Texas, Kentucky, Mississippi and Arkansas, and whose paternal grandparents hailed from Alabama and Tennessee, I’ve seen my share of Southern racism and small-mindedness as surely as I’ve seen the South’s storied hospitality, savored its diverse cuisines, and felt the honey of its drawl lilting over my eardrums. Although the South’s politics tend toward conservatism and many of its historic policies have wound up squarely on the wrong side of history, there are plenty of progressives in the South, and they tend to huddle in coteries, like expatriates. It should go without saying that there are plenty of Southern conservatives who are not bigots, but in our polarized era, even the obvious bears overstating.

The fact is, though, that as my trip to Florida neared, I was more than a little on guard about spending thirty days in a state governed by Ron DeSantis, populated by throngs of beach-partying anti-vaxxers, and some of the nation’s highest rates of Covid infection, hospitalization, and death. In early June, when my sojourn commenced, I was coming from a Portland that was still rigorously masked.

In Orlando, where much of my family lives, the majority of supermarket shoppers and strip-mall hoppers were wearing masks, but when I ventured farther afield to cities like Mt. Dora, Sarasota, St. Augustine and Jacksonville, masks grew scarce, and nobody seemed to care. It’s uncanny how quickly one feels like a stick-in-the-mud, wearing one’s face-condom like a good boy or girl when everybody around you is partying like it’s 2019. The first time I walked into a bar and saw maskless people crowded next to one another, my jaw dropped. I hadn’t beheld such a sight in more than a year and three months back in Portland, where bars were roped off because, quite simply, you can’t socially distance on a barstool only inches from your fellow drinkers. As my four weeks in the Sunshine State continued, however, a strange thing happened. I started to like not wearing a mask and congregating with other people who weren’t. Granted, I was vaccinated, and granted, I had read that back home in Oregon, our governor, Kate Brown, had announced she’d be ending Oregon’s mask mandate effective June 30, so I rationalized that my time in Florida was basically a practice run for how things would be when I returned to the Northwest. Still, it was instructive to watch myself become inured.

Other than the mask situation, relatively few things felt foreign to me as a wayward native son. Florida drivers are faster and more aggressive than Oregonians. There’s more weaving and less use of turn signals. There are more pickup trucks, and they’re very big. There are more churches and more gun/ammo stores. There’s a gigantic 30-by-50-foot Confederate Battle Flag flying on private property near the intersection of Interstates 4 and 75. And yes, there are way more pro-Trump and “Stop the Steal” bumper stickers. Most of my relatives have the good sense not to talk about politics in family conversation, so there wasn’t much in the way of interpersonal friction. On the whole, Florida didn’t feel particularly exotic to me, nor sinister, with the exception of that huge, brooding flag, which was clearly beyond the pale and struck me as downright spooky.

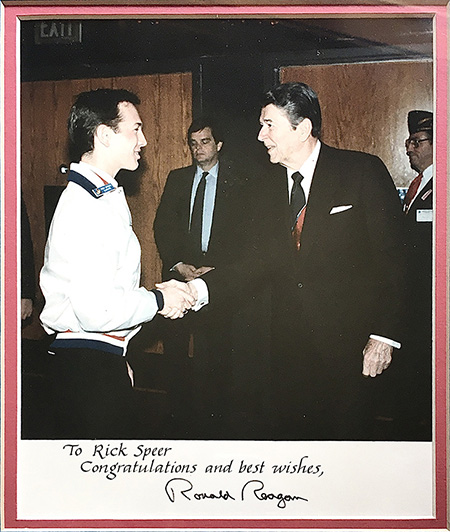

My history with Florida politics is checkered. In high school, I had won a speech contest (“The Voice of Democracy” competition, sponsored by the Veterans of Foreign Wars), for which I was rewarded with a trip to Washington, D.C., to meet then-President Ronald Reagan. For a 17-year-old, this was a heady experience. Given that my grandfather had been a card-carrying member of the Republican National Committee; given that I’d spent my high-school years on American Army and Air Force bases in Germany, immersed in the ethos of the military; and given that I’d just read Ayn Rand’s “Atlas Shrugged” and was energized to consider myself a budding “Objectivist,” the impressionable young me got nudged beyond the tipping point by meeting Reagan. I must be a Republican, I mused.

Back in Florida for college after leaving Germany, I signed up with the Orange County Republican Party to campaign for that year’s presidential nominee, George H.W. Bush. That’s how I wound up one afternoon in the sweltering Florida heat and humidity, walking around my subdivision, knocking on doors, proffering brochures and yard signs, urging voters to elect Bush the Elder rather than his opponent, Michael Dukakis. After a few hours, it occurred to me to rest for a moment in the shade and actually read the brochures I was handing out. They touted Bush as a pro-life, anti-gay candidate who supported prayer in the schools and the N.R.A. I had known these things about Bush but had opted to overlook them. Something about seeing all this in black and white, however, threw into relief the hypocrisy of my support. I was a strong supporter of a woman’s right to choose, as well as responsible gun control, gay rights, and the separation of church and state.

In that moment I asked myself: Why are you doing this? Is it just because you were glamorized by meeting a President of the United States and got a rush from the proximity to power? Is it because you’re aspirational about money and associate the G.O.P. with entrepreneurship and wealth? Or is it because you’re always looking for father figures, and to you as to so many Americans, Ronald Reagan seemed like an avuncular patriarch, and Bush his nerdy nephew, even as they blasted the arms race into space and oversaw a massive military buildup? With a leaden sigh I took the placards and brochures to the nearest dumpster and heaved them in. That was my first and last afternoon campaigning for the Orange County Republicans.

In the years and decades that followed, I became a Libertarian, then an Independent, then finally a Democrat. Call me a dilettante, but I like to research my options. I parted ways with Ayn Rand over her nasty remarks about gay people and modern art, but I continued to think of myself as an advocate of reason over faith and individualism over statism. I’m fiscally conservative and socially progressive, along the lines of former Massachusetts governor William Weld.

Moving to Portland in 2000 no doubt moved me farther leftward, as did writing for an alternative weekly, moving in the circles of artists and writers, and growing increasingly fatigued by Republican-instigated culture wars, born of the perverse, purely pragmatic alliance between the G.O.P. and the religious far right. In more recent years, the specter of Donald Trump and the sycophancy of the Republican establishment and rank-and-file to his whims has proved that any pretension of principles (limited government, lower taxes, personal responsibility) among the majority of Republicans has yielded to blind loyalty invested in a petulant, anti-intellectual, narcissistic fabulist. Say what you will about conservative pundits like George Will and the late William F. Buckley, Jr., their voices have been drowned out by the populist mob that stormed the Capitol and still seek to delegitimize a fair election.

Which brings us back to Florida. Trump won the state in 2016 and again in 2020. He lives and holds court in Palm Beach. His son-in-law, Jared Kushner, is establishing an investment business in Miami. This is also the state of Marco Rubio, Matt Gaetz, and Ron DeSantis, who is not only the state’s governor, but a leading contender for his party’s next Presidential nomination. Clearly, my home state has some issues, and not just the absurdist sort that has made “Florida Man” the punchline of a thousand memes. Still, the white sand, warm waters, and swaying palms of Clearwater and Key Largo have no political affiliation. The flamingo’s feathers are pink, not blue or red. Deviled crabs, hush puppies, fried plantains, and grits taste the same whether you watch MSNBC or OAN. It’s a complicated place for a leftie to go home to.

I am a Floridian by birth, an Oregonian by choice, a patriotic (not nationalistic) American by fate, and a citizen of the world by predisposition. I do not believe that all Democrats are good and all Republicans evil, nor do I think political candidates should be voted in or out because of single-issue litmus tests. Context counts. I continue to believe that more than 50-percent of Americans, regardless of party, would gladly pour you a glass of lemonade on a hot day and help you find your dog if it wandered away. Those virtues are not political or geographic, they’re human. Maybe we can get back to those values if the poison of polarization hasn’t seeped too deeply into our pores. We can’t look for bipartisan spirit in the halls of government, though. It has to start with ourselves — with unvarnished introspection, a rooting-out of our under-the-radar prejudices. The times call for a commitment to agree to disagree when consensus is optional, but to organize and resist when compromise isn’t an option. And the wisdom to know the difference. That isn’t a recipe for solving the world’s troubles, but it’s a good start.