Continuing through September 18 2021

Concurrent exhibitions showcase works from the 1980s by two well established artists, Lee Bontecou and Michelle Stuart. Bontecou, who is best known for wall sculptures made of rugged materials such as laundry conveyer belts, is represented by a handsome suite of drawings executed on 8 1/2 by 11 inch graph paper. Stuart’s exhibition consists of her characteristic abstract topographical landscapes made by combining encaustic with pigments, earth and plants.

Although both artists rely to some extent on a use of the grid, their approaches to process and content are at opposite ends of the spectrum. Bontecou’s drawings originate entirely in the artist’s imagination, while Stuart’s modular paintings are simultaneously analytical and emotional responses to empirical observations. For Bontecou, the grid of the graph paper is an empty stage whose existing geometry can be advantageous in guiding placement or studying proportional relationships. For Stuart, the grid is something to construct from modules, thereby adding a sense of monumentality that conveys the vastness of physical landscape.

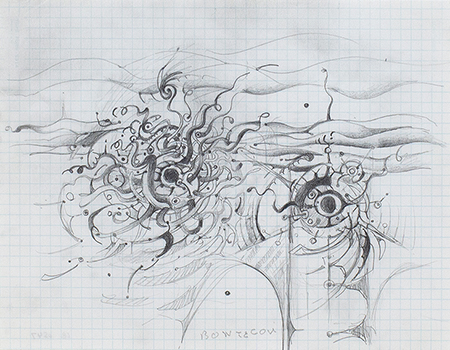

Bontecou’s drawing practice has always run parallel with and been closely tied to her sculptural explorations. Many of her familiar subjects, such as the circular void or eyeball and fantastic birds and animals, appear in both bodies of work. In these drawings Bontecou probes these subjects from multiple vantage points and with varied details and textures. In one example, a birdlike creature with splayed limbs is depicted twice. Positioned side by side, it is drawn very faintly on the left and with great density on the right. In a related drawing, the same subject stretches across the entire page as if soaring through space, an effect that is facilitated by its being superimposed over visible erasures that lend a sense of movement. In another work, a profile of a bird’s head is depicted diagrammatically over a grouping of rectangular structures, a juxtaposition that yields a dynamic tension between geometric and organic forms. In another that resembles a pair of one-eyed octopi immersed in an aquatic atmosphere of wavy lines, the composition evokes narrative overtones.

While some of Bontecou’s drawings suggest complex, expansive universes, the most elegant in the group are the two that relate most directly to her characteristic wall sculptures, featuring her familiar oculus. In both, the focus is on a centrally placed eyeball around which the rest of the drawing revolves in a circular or centrifugal motion. In one, linear striations extend outward from the eye of a bird while, in the other, a cycloptic being stares directly at us while the rest of its head breaks into fragments.

Stuart approaches her process of mixing pigments with site-specific earth materials from the perspectives of both an artist and an archeologist. Although other women artists of her generation have used similar methodologies to explore concepts of spirituality (e.g., Lita Albuquerque and Beth Ames Swartz), Stuart is more interested in recording her experiences of visiting particular locations through recreating their physical attributes, but with a poetic temperament that only an artist can provide. Here she sensitively replicates the colors and textures of places she visited in Alaska, Arizona, Hawaii and New Mexico.

Although Stuart’s paintings are geometric in shape and largely monochromatic, it is the interplay of colors and/or textures that produces their subtle energy, one that changes depending upon how closely we approach the work. When seen from a distance, “Winter Light, Alaska” might be perceived as simply a solid, minimalist mass. Closer inspection, however, reveals a shimmering surface — the effect of graphite and aluminum powder interacting with gallery lighting — that reminds us that the place being documented is beautiful, precious and inspiring. Similarly, “Night Ship Creek, Cook Inlet, Alaska” seems to alternate between looking like open terrain and a starlit sky. By contrast, the warm rustic browns of “Pueblo Bonito, Chaco Canyon, New Mexico” and the optically lush intermingling of greens and reds in “Xochitl II” make a strong case for nature lovers to book a flight to New Mexico.

Stuart’s exhibition also includes a series of early drawings that reveal the origins of her interest in topography, as well as three small collages in which plants are beautifully preserved like treasures in a memory book.