Let me look back for just one second, a second that extends back to 1965 when I was 13 years old, and in that late spring evening I wrote my first poem. It seemed to pop up out of nowhere. I was a somewhat melancholy and introverted youth, prime bait for puberty’s loopy hooks, and writing a poem felt intuitively as the only way I might relieve something that I had no name for. It was cliché-ridden, sentimental, and thoroughly honest and heartfelt. It wasn’t good. But poem followed poem followed poem. Not surprisingly I became an English major in college, but truth be told poetry in American University English departments, or at least mine at that time, didn’t treat poetry as art, but as history, or sociology, or political science or psychology. The professors seem to think poetry was philosophy that “meant” or “figured out” something. Yet behind their backs, down through the ages, in countries and cultures as disparate as you’d like to suppose them to be, poets not only knew that poetry was art, but artists of every ilk perceived it as the art form to which theirs aspired.

In the mid-1970’s. after college I moved to Berkeley, where my eyes were opened to visual art for the first time. I have one person to thank for this, Joseph Slusky, a marvelous metal sculptor who eventually would teach free-hand drawing to Architecture Students at UC Berkeley. How much did Joe love poetry? He had taped every record of poets or actors reading poetry from the Spoken Arts section of the Berkeley City Library and would play the likes of Wallace Stevens, William Carlos Williams, Emily Dickinson, Robert Lowell, John Betjeman, Sylvia Plath, Jack Kerouac, W.H. Auden — the list extends in many directions — while he was hand painting his welded steel sculptures. It seems that listening to poets read their work put him in a relaxed and meditative mood best suited for his painting. Through my friendship with Joe I began to meet many other visual artists in Berkeley, the Bay Area and beyond. As if it were a mantra Joe would introduce me to his artist friends by saying, “this is Andy, a poet,” by which as if entranced they would instantly welcome me as one of their own. For the first time I knew that I, a poet, was an artist too. Not that it made me unique. They said in Berkeley back then that “if you threw a stone, you’d hit a poet.”

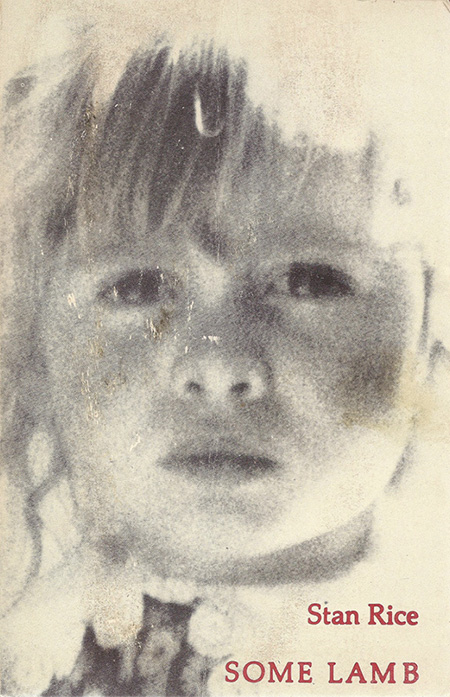

One of my metaphorical hurls, released with all the tenderness an oxymoronic assault with a rock might muster, hit Stan Rice. Rice was an Adonis-like young super-star poet in the Bay Area, barely past thirty. He was also a painter. As if he needed a “what’s more,” what’s more, he was a brilliant thinker about poetry and art who, while I was in a graduate poetry writing class that he was teaching, introduced me to the American philosopher of art Susanne Langer. So deeply into Langer’s writing (check out “Feeling and Form,” “Problems of Art,” and “Philosophy in a New Key”) had Rice dived that his wife, novelist Anne Rice, referred to her as “the other woman.” Sadly, Stan died from brain cancer at age 60 in 2002. He was one of the best poets of his generation, from his early “Whiteboy,” which earned him the Edgar Allan Poe Award from the Academy of American Poets, to the posthumously published “False Prophet,” which bookend a string of excellent collections.

In “Feeling and Form” Langer offered, explicated, explained and defended her definition of art. Philosophers work by examining the already existing philosophies of others, then go about trying to dismantle the competition until, with the sudden blow of a boxer’s knockout punch, they simultaneously deliver and declare their philosophy of the matter at hand as the one true version. Drum roll please, loud enough for Stan Rice to hear, on page 40 of the 1953 green paperback edition of “Feeling and Form” we find Langer’s definition of art: “Art is the creation of forms symbolic of human feeling.” Simple in appearance, simple it certainly is not. Langer applies it with astonishing erudition to an investigation of how pretty much every form of art — painting, sculpture, photography, dance, music, poetry, fiction and theatrical drama — fleshes out her thesis. Those who have read my poetry and reviews over the last 40 years have experienced my effort to apply Langer’s philosophy of art to both.

This preamble has landed at the place where I intended to begin in the first place, the inexact intersection of the two intricately linked yet confounding different worlds of alternately writing poetry and writing literary and art criticism. Having done both, I appreciate Oscar Wilde’s typically sardonic observation that, “The critic is even higher than the artist, because he stands on the artist’s shoulders.”

Here is why I do both. After I had established myself a bit in Berkeley, some of the poets and artists I knew would solicit me to review their book or art exhibition. I think they felt that “it takes one to know one,” and since they saw me as one of them, they had confidence that I could feel their work and therefore write about it. Looking back, I’m touched and honored that they did, and it led to my making lots of talented and interesting friends. All I ever tried to do when reviewing poetry and art is feel the symbolic forms of human feeling in an artist's work then find, however inadequately, the best discursive language available to me with which to share my thoughts and observations about it.

Writing poetry, however, couldn’t feel like a more different experience.

I am often asked, “What are your poems about?” I bite my tongue not to reply that that it is the word ‘about’ in the question that is pejorative. To talk about what a work of art is about puts the critic on the artist’s shoulders and drives them into the ground.

When I write a poem, throughout the process of its creation I feel an experience of total freedom and joy. There’s the wildness akin to being strapped on the back of a bucking bronco, or drifting akimbo on the drafts of a hurricane force wind, yet feeling as sedate as taking an old and faithful pet dog out for a walk. A poem, or really any work of art, is a “creation,” which means it didn’t exist before I made it exist.

One might say an omelet didn’t exist before someone made it, or a made bed forges a new form when compared with the unmade bed that preceded it. So, are the cooked eggs and cheese omelet as well as the sheets and blankets laid nicely now on the mattress “works of art” because they are both new creations? Duchamp may have ruined everything by saying anything can be a work of art if the artist says it is, but I say that a cooked omelet or a made bed do not qualify as art at all.

Here’s a new poem, completed just before I started writing this dichotomy.

Autumn Sweater

Mild August

the parrots

the figs darken

as night

leaps more

quickly

towards day.

I too have

come to

accept a backwards

motion

a future

cooling in its

darkness

aimed at

finding life’s

warmth.

There are other

parrots, greener

in their awkward

youth,

and rounder figs

afraid their

sweetness

will one day

scent

the

mouths

of

the undeserving.

But what else

can Autumn do

but terrify us

with the

thought

of heat’s

thieving

stealth?

Nothing but a

a sweater

can warm

me now.

If I didn’t like the direction the poem was going in while I was writing it I’d pivot, like LeBron James in the paint, in a new direction. If I began to feel stuck in the writing because I didn’t know what I was talking about, I’d jump into the stronger current of not knowing and stop thinking about that pejorative word ‘about’ and just keep navigating the waters that eternally flow beneath understanding. As Stan Rice once told me, “At its core, the essence of poetry is non-verbal,” because it is a symbol of feeling and not a statement of facts, and the essence of feeling’s spiderweb-like momentum cannot be captured located in language’s discursive map.

This essay is in part an homage to both Slusky and Rice. I met Rice through Slusky, as those two artists were good friends and great admirers of each other’s work. So I’d like to end it with two of their symbols of feeling.

First, here is a poem from Rice’s remarkable book, “Some Lamb” (The Figures Press in Berkeley, 1975). The occasion of the book couldn’t have been more tragic, as the poems carve out symbols of feeling that punctured the poet from the dying and death from leukemia of his and Anne Rice’s six-year-old daughter Michele. The entire book pulses with the organic force of grief, the staccato rhythms of one full life tragically fulfilled in six too-short years. Some might feel the material here is just too heartbreaking to turn it into art, but that’s just what Rice heroically did. Here is “Michele Fair,” which through my tears I can barely transcribe:

Michele Fair

The Substance Beast is very cruel.

It plants me in the oil school.

It beats my knuckles with a stool.

I’m chained to it like fists to fools.

I wish I could be like Michele Fair,

Who dug her grave in her yellow hair

And took off her clothes and stood there

Waiting for the Beauty Bird.

She hummed and murmured I Don’t Care

When the truant officer cut her hair

Off with a set of silver tools.

But the Substance Beast keeps check on me

To see that I have fed it me

Just as policemen like to see

A proper show of humility in those they rule.

Someday maybe I’ll be like Michele, free-flowing

Baldness, at night regrowing the yellow hair

That covers the grave she’s dug to snare

The Beauty Bird, the Naked Knowing.

The poem’s emotions swirl up and through the pain that wants to drown it. It is a silent dirge that transforms Rice’s private feeling into a personal tombstone of empathy. Reading “Some Lamb” makes us all more human and alive. It’s one of the best books of poetry of our time.

The second is an image of Slusky’s hand-painted welded steel sculpture, “Tantric Anagram.” Just as Rice’s book stops us in tragedy’s tracks, Slusky’s sculpture winds up the life force again for us and points us in a cat’s cradle intertwining cosmically gestured direction toward what life still holds in store. Oh, and while we’re at it, let’s all get off our artists’ shoulders and let them ascend back onto ours, where we can admire and love them, and from which they can deliver their symbolic forms of human emotion down for us to use, and use them as never before.

# # #