Continuing through November 13, 2021

The Black Lives Matter movement and the seismic changes brought about by the covid pandemic have revealed to mainstream America that the nation’s history of racial oppression will not be expunged or whitewashed by a white-supremacist backlash. Not even as the nation edges toward demographic minority-majority as soon as 2025, as the president of the Bank of America told the artist Carrie Mae Weems, in the 1980s. The culture is changing, reflecting this new reality, and we cannot return to 1950, or 1850 or 1619, when slavery was first ushered into the New World.

One of the most tireless champions of a new historical consciousness is multimedia artist Weems. A Black woman who decided to “dig in my own back yard” for subject matter, Weems has used photography, along with performance, recorded speech and video to document and interpret the history of racism in America. Often using herself as a model, thus serving as both subject and object, she has helped bring the Other — Black, female, non-WASP — a fresh cultural visibility and respect. “Witness,” a selection covering her four-decade career, is a subset of Weems' 2013 retrospective, seen locally at Stanford’s Cantor Art Center before it traveled to New York’s Guggenheim Museum and beyond. The show is accompanied by a new scholarly-essay monograph from the MIT press.

“Witness” is an apt title, given Weems’ role as silent observer in her “Louisiana Project” (2003) “Roaming” (2006) and “Museums” (2006) series. Garbed in flowing white or black dresses, facing the grand historical architecture of cultural institutions in Rome, Paris and Washington D.C., as well as plantations in Louisiana, with her face turned from us she becomes a witness to history and the viewers’ surrogate. Like the Rückenfigur, a person seen from behind, contemplating the view in Caspar David Friedrich’s iconic “Wanderer above the Sea of Fog” (ca. 1817), she is a still, powerful presence — yet small in relation to the landscape: “history’s ghost,” as the retrospective’s curator Kathryn Delmez put it. Weems’ impassioned but dignified, even stoic work bridges the divide between documentary photography, with its hard realities — sometimes too sentimental and victimizing for the artist’s taste — and fine-art photography, with its aesthetically alluring form, which Weems considers important to draw us in. Images become a “porthole” of “beauty, elegance … grace,” but only in the service of a larger context, never to be indulged in for its own sake.

“I attempt to create in the work the simultaneous feeling of being in it and of it. I try to use the tension created between these different positions — I am both subject and object; performer and director.”

The exhibit is in roughly chronological order, with some deviations from that probably necessitated by layout considerations. “Dad and Me” from “Family Pictures and Stories” (1981-82) is an early portrait of the artist as a young woman, sitting in the paternal lap, accompanied by a typed quotation: “See Carrie Mae, what I like about you is you can talk to them white folks, and you’s smart, too, just like your daddy.” “Mom at Work,” also from “Family Pictures and Stories,” shows a seamstress who appears to exult in her life, her work, and her smart daughter’s photographic attention. The poet Elizabeth Alexander writes of “the black interior … behind the public face of stereotype and limited imagination … complex black selves, real and enactable black power, rampant and unfetishized black beauty.” This depiction of Black humanity, as rich and complex as its white-default counterpart, comes into further focus in Weems’ “Kitchen Table Series” (1990), a sequence of photographs all shot from a stationary tripod centered on a butcher-block table beneath a conical hanging lamp — a basic stage set — with the charismatic artist appearing in different clothing, interacting with various family members. It’s a group of images, each with its own narrative: a time-lapse movie, shot in stills, akin to Cindy Sherman’s early masterpieces of film stills from imagined films, with herself in each role.

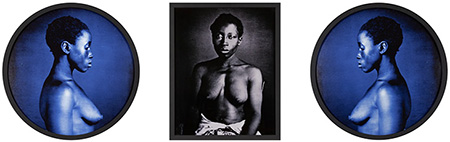

In “From Here I Saw What Happened and I Cried” (1995-6) Weems disappears from the images and takes on the role and voice of an invisible archivist, historian and commentator. In the mid-nineteenth century, the naturalist Louis Agassiz, pursuing his polygenetic theory that the human races are not one, but separate species, commissioned Joseph T. Zealy to produce series of ostensibly scientific photographs of selected plantation slaves, naked, in profile and full-face. Weems, visiting Harvard’s Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology, happened upon the surviving daguerreotypes — unique objects, remember, not duplicates — and apparently took them covertly to photograph, despite having signed a contract requiring permission to publish. Weems enlarged and cropped them into tondo formats, and tinted them red or blue, transforming these demeaning displays into sober indictments of racist scientism. The artist also superimposed text over the photo portraits, à la Barbara Kruger: for “Delia (A Photographic Subject),” for “Jack (An Anthropological Debate),” for “Renty (A Negroid Type),” for “Diana Portraits (Younger Woman).” The latter is a triptych of photographs, with the blue-tinted left and right profiles facing the full-face black-and-white frontal shot, and, with the caption deleted, Diana’s humanity retrospectively restored. The artist successfully dared Harvard to sue her for publishing the image, saying that she welcomed a public debate on whether the images of slaves, taken under duress, fall under current copyright law. (A current lawsuit by the family of Henrietta Lacks, a woman whose cell tissue, removed without her consent, was used for medical research, is analogous.)

“I wanted to uplift them out of their original context and make them into something more than they have been. To give them a different kind of status first and foremost, and to heighten their beauty and their pain and sadness, too, from the ordeal of being photographed.”

“Witness” offers this and so much more to view and to come away with. There is the obviously staged yet still moving 1968 Kennedy/King assassination tableaux; Weems’ studies of the symbolism of African architecture; her performances and videos; her commemorations of black women performers. If you missed the 2013 show, you may now rectify that historical error.