Continuing through November 20, 2021

A global perspective on contemporary art sets Asian artists such as Jiyoung Chung in a different light. Educated in both South Korea and the U.S., she single-handedly revived an ancient dyeing-and-papermaking tradition known as joomchi. Pulping and felting papers made of mulberry leaves, Chung came up with wall-mounted “paintings” that have strong echoes of midcentury modernist American artists such as Helen Frankenthaler, Jules Olitski, Robert Motherwell and others. Instead of emphasizing flatness, the cardinal virtue of abstract painting according to critic Clement Greenberg, Chung adapted repetitive imagery and turned Greenberg’s “shallow picture plane” into a stack of perforated and punctured pieces of paper overlaying one another, fluttering slightly on the gallery wall. Her explanatory workshops and exhibitions all over Europe, Asia and the U.S., testify to the Korean ambition to put their art on the international map and to cement Korea’s primacy in the huge heritage of historic East Asian art.

Historically, Korean art has been overlooked or neglected compared to Chinese and Japanese art. Its greatest asset has also been its greatest liability: it is a geographical peninsula surrounded on all sides by China or Japan. This allowed for isolated innovation, but also made such inventions vulnerable to Chinese and Japanese invaders. Recently, closer looks by Korean art historians have led to very different conclusions about who was first. For example, many Korean academics now claim archaeological shards found in China of the famous grey-green celadon glaze can be traced to Korea, suggesting the celebrated glaze (with over 200 different shades) came from Korea in the first place. Similarly, several Japanese ceramic and metalwork styles arising as early as the seventh century AD are now considered the result of the forced migration of over 800 Korean artisans to Japan. Works on paper and metal have their own histories of innovation, invasion and expropriation. Chung is doing her best to update the record and give credit where it is due.

Making art, teaching it, exhibiting it and curating exhibitions around joomchi have kept Jiyoung Chung busy since her graduation from Rhode Island School of Design (BFA, 2002) and Cranbrook Academy of Art (MFA, 2005). Her book on the topic, “Joomchi and Beyond,” the definitive historical study with contemporary updates, appeared in 2011.

As stark and formal as they appear, each work is subject to breezes, flutters of air, and movement of viewers as they inspect the pressed surfaces that have open space between each layer. Subtly kinetic then, focusing on perforations, natural and pigment dyeing techniques, and highly varied textures of handmade paper, the objects activate each wall. Chung, whose work has been respectfully received in Japan, has also found resonances in other countries with textile, paper and fiber craft or folk traditions, such as Romania, Finland and the Netherlands.

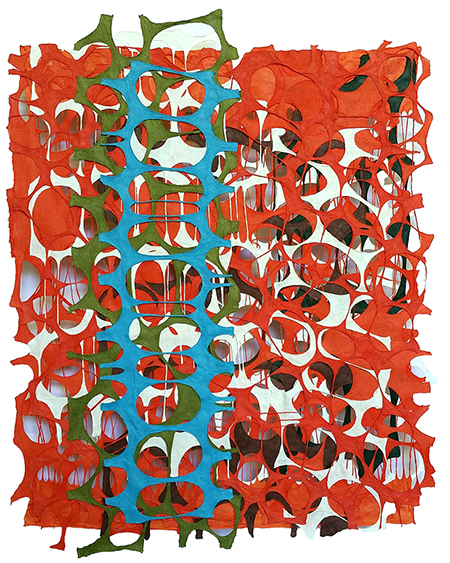

The main difference between Chung and the American Color Field painters is scale. Her work is intimate, bordering on the precious. The Color Field artists worked, except for their prints, to a large scale, enveloping us in color and texture. Chung’s largest work, “Enriched” (2019), is a tall rectangle, 68 by 30 inches. Her smallest, the “Seeds” series, (“Voice I,” 2020), is a box of enclosed natural seeds that is 9 inches square. We can perceive the infinitely painstaking activity of melding, blending, dyeing and punching out the wet sheets of paper. This apprehension activates a sense of workmanship, determination and unexpected sights, all typical of classic Korean art, not to mention joomchi. “New Perspective” and “Growth” (both 2020) are the most colorful, their torn grids stacking layers of red, black and blue in the former, and blue, yellow and red in the latter. Averaging three feet square, these are unexpected, non-harmonious color combinations that nevertheless work well together.

While most have a gridded, all-over composition, several are muted with darkened fields beneath the cascades of torn holes and jagged paper edges. “Contented II,” “Seeds: Strength in Weakness” (both 2020) and “Contemplation” (2021) are moodier, suggestive of stronger emotions that are often concealed by Korean cultural etiquette protocols. Here they seep through the holes and leaks, bleeding out onto the crusty papers. Thrifty without wasting any scraps, Chung’s “Seasons in Life” series (2020) incorporates colored paper scraps tightly crammed into small 8 by 10-inch glass-covered boxes. Less kinetic but more brightly colored, this series suggests the extraordinary range of variety joomchi is capable of and the brilliant new experimentations with the medium that Chung has achieved. The “Whisper” series (2020) is even tinier, white-on-white paper cutouts also 8 by 10 inches in size. Though each is a different conglomeration of cut scraps, they border on a repetitive tile format, leaving us with the questions of how long can the grid format last and how small can a work be before it degenerates into a decorative module? With this substantial body of work and its remarkable variety of colors, textures and approaches, Chung advances global craft media as well as the long history of art on the Korean peninsula.