Continuing through January 31, 2022

In terms of his notoriety, Tony Fitzpatrick’s creative output and his personality go hand-in-hand. And so, when this iconic Chicago artist announces that this exhibition, “Jesus of Western Avenue,” is his final solo museum show, those of us who know the man believe that he means it. Fitzpatrick’s is a wide-reaching creative life, with visual art, books, poetry, articles, plays, album covers and television characters under his belt. So his decision to take himself out of this particular portion of the art world game is meaningful precisely because he is at the top of his game. Fitzpatrick, by his own account, is removing himself from the equation to make room for historically and systematically underrepresented artists. Over the years, the artist’s generosity has often taken the form of access — to fine art for the public and to meaningful opportunities for emerging artists; and Fitzpatrick’s affinity for access makes its way into his visual artwork, as well. His practice features a specific sort of Midwestern Americana, blending the aesthetics of comics, vintage advertising, matchbooks, prayer cards, snippets of sheet music and Chicago-specific iconography. It’s a vernacular that allows so many different kinds of viewers an entree into the work.

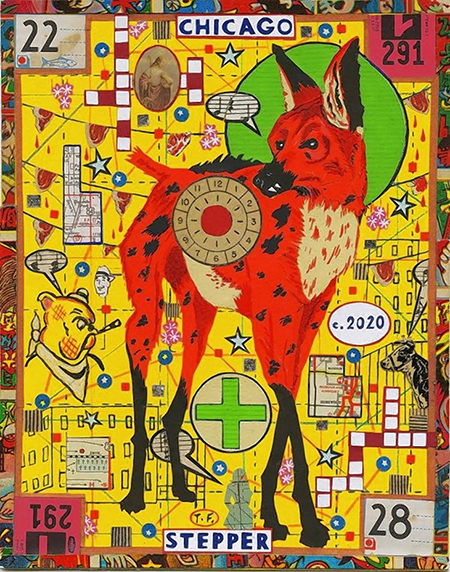

The works in “Jesus of Western Avenue,” mainly produced during the past decade, vary in subject matter but are remarkably consistent in style. Fitzpatrick’s aesthetic is hard-edged and gritty, with a Pop sensibility that is decidedly more blue collar and Imagist than slick and Warholian. An aura of the past permeates these works on paper (most are part drawing, part collage), though Fitzpatrick wields it in a way that stops short of nostalgia. There’s no longing or sentimentality here, and Fitzpatrick is pandering to no one. It is a past that feels quite alive.

In “Western Avenue (Street of Crocodiles)” (2021), caped superheroes, pinup girls and Dick Tracy-type characters with cigarettes dangling from their lips commingle with contemporary fast food and gas station signs atop a drawn grid resembling the layout of Chicago’s streets. Throngs of tiny, cut-out comic book characters in “Humboldt Park Winter Juncos” (2021) fill the background behind the carefully rendered birds of the piece’s title. In these works, like most others in the exhibition, a patchwork of everyday emblems of the past ground Fitzpatrick’s subjects, much like the way in which we lead contemporary lives in and around the historical remnants that shape Chicago.

As much as Fitzpatrick focuses on the familiar, his works are never obvious. Even the smallest details in these works (some of the cut-out, collaged figures are less than an inch high), are curiosities. In “Humboldt Park Tern (Longing for the Sea)” (2021), tiny cherubs sport kitten heads on their shoulders, while grinning skulls replace faces of the saints in their ovoid portraits. A spindly tree in the background of “Monster Bird Deep in the Brick Heart of Chicago” (2015) has miniscule raw steaks speared upon its branches, dripping the blood that dots the negative space of the entire piece.

The revelations here are not all dark, though. While Fitzpatrick has incorporated animals of all kinds as the primary subjects and symbols of many pieces from this decade, his pandemic collages are indicative of a newly acquired habit: birding. Flora and fauna are not usually what comes to mind when thinking about the dense, man-made grid that is the city of Chicago, but here Fitzpatrick catalogs the avian life of Chicago’s green spaces like an urban Audubon. Humboldt Park, the 200-acre park in the vicinity of the artist’s stomping grounds, figures largely, its name emblazoned across the pieces. Terns, herons, juncos and woodpeckers are among the species immortalized, their unique likenesses rendered carefully and with haloes about their heads, both at-home in and in contrast to the density of the drawn city grid in the background and its crowded occupants.

There is so much packed into each of Fitzpatrick’s pieces that viewing them is a lengthy but engaging process. It’s not just the sheer volume of detail that holds our attention. However imaginative these details may be, none of the chaos is random. Seeing so many stylistically similar pieces in one place makes it so much more clear how Fitzpatrick has taken a vernacular visual language, one that we’re so familiar with, and parlayed that into a lexicon that’s specific to him. From piece to piece, motifs recur: the hanging meats, strings of pennants, crossword-puzzle-like blocks, strips of cut-up matchbooks framing the scenes. What are the radial, circular forms overlaying the hearts of each of his birds, punctuating the space around his crocodiles, or reiterating the symmetry of his Green Mill sign? Roulette wheels? Dart boards? The sunbursts of Mid-Century decor? The incorporation of such elements is too regular to not be symbolic, though it feels like one could just keep looking and wondering, and perhaps never really crack that code.