Many of us — not all, alas — are in an introspective mood these days, as we confront difficult problems amid portents of social collapse: however did we get here? Gauguin’s great 1897 painting, “Where do we come from? What are we? Where are we going?” asks big questions, but its answers are aesthetically coded in “the pictorial language of feelings” — not today’s bullet points or sound bites. But it does set the stage.

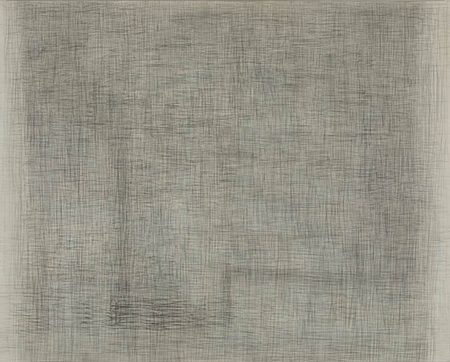

Robin Kandel’s current exhibition, with its intriguingly enigmatic title, “It Was a Place Beyond Compare with a Magnetism Like No Other,” shows the artist paring down her means and working spontaneously. Kandel is known for densely worked abstractions composed of ruled parallel stripes that reference landscapes, journeys, and memory: large unstretched canvases, hung by grommets and crisscrossed by folds, like glove-compartment maps; paintings on panels traversed by angled stripes that suggest lacustrine rippling waves; and square-foot drawings suggestive of graphite-embossed topographies. Here, the artist limits herself to a nostalgia-charged Dixon Ticonderoga No. 2 pencil and prepared panel and paper (coated with and acrylic ground that simulates the texture of drawing paper). Paul Klee said, “A line is a dot that went for a walk,” and ”A drawing is simply a line going for a walk.” Kandel’s unconstrained pencil, “wandering the streets of old local maps and across scraps of earlier drawings,” creates psychic maps that inquire about directions, “So, where is this place and how do we get there?“ Gauguin, meet the Talking Heads (“Once in a Lifetime”).

The open-ended, experimental nature of the work is revealed in its manifestly hand-drawn look. A background plane or membrane of horizontal lines is contrasted with ghostly foreground structures, sometimes orthogonal, sometimes organic, that derive from highways, boundaries, shorelines, and other features from maps. Klee used stratigraphic parallel horizontals, too; and William T. Wiley’s charcoal-on-canvas manuscript-maps also come to mind. The resulting spatial push-pull between landscape and the structures created by the artist’s wandering pencil lends the works their rich variety of associations, including the archaeological and the phantasmic. The present, deriving from the persistent past, is merely a way-station on the road to our unknown destination. Kandel, on her holy wandering creative process says, “I can say that making the work felt like a bit of controlled chaos, which felt like what I was experiencing on a daily basis. Each prepared panel piece has multiple drawings beneath it. No evidence of those drawings exists. I found that the more I abandoned control, the more I recognized my results.”

Kandel’s poetic titles eluded my search for sources: “we were lost — absolutely and completely lost;” “we cursed the map and its failed coordinates;” and “with infinite geographies tucked into pocket; the drifting was familiar and somewhat unpleasant”. To my ear they sound like a voyager’s tale of woe and intrigue from Edgar Allan Poe. Even better, it turns out they just came to her unfiltered, like the radio messages to Orpheus in Jean Cocteau’s film. The artist explains, “… many of them came to me upon waking, a kind of (subconscious?) reflection of muddling through these times. Of course, I batted titles about and massaged them into place. The feeling though remained, of being ‘absolutely lost’ or cursing ‘failed coordinates’ on a map (even though I know map coordinates are basically useless today) … Truly, I keep thinking to myself, where is this ‘place beyond compare’ and how do I get there?” Kandel’s meditative mental maps, like other deeply serious art, show a way past the cynicism and despair of our troubled times.