Continuing through March 5, 2022

In ten works created over the past decade, veteran photographer Jeff Wall really puts our powers of observation to the test. In these characteristic large-scale digital prints, in which everything appears life size, Wall cleverly toys with our perceptions of what we are seeing. Carefully constructing each scenario as if he were directing a movie, the artist employs performers (a more apt term than “models”) who enact what he calls “near documentaries.” These may seem believable at first glance, yet no narrative or storyline can ever be fully determined, as the implications of the performers’ actions always lead to open ended speculation, and illogical details may thwart any interpretation at all.

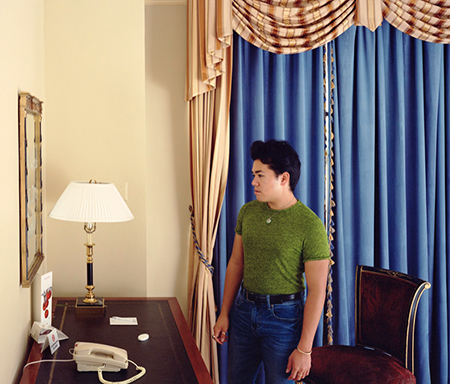

During the 1970s and ‘80s, Wall earned considerable acclaim for his pioneering backlit photography. He mounted large photographic transparencies over light boxes to bring a cinematic quality to his imagery. In his more recent digital prints, it is photographed light that plays a pivotal role in establishing a mood and directing our attention to or obscuring it from activities within a composition. In “Man at mirror,” for example, a table lamp illuminates a mirror with writing that we cannot read because it faces at nearly a right angle within the composition. But it is the focus of a young man staring at it.

In “A woman with a necklace,” intense daylight behind a curtained window pulls our gaze away from the main subject, a woman reclining on a couch contemplating a necklace, making it difficult to discern her features or the objects on the table in front of her. Carefully orchestrated positioning of table lamps also moves our eyes through two different views of the same common living room (actually a room in Wall’s home) in the diptych “Pair of Interiors.” In this subtly deceptive psychological drama, a couple is shown in two different types of interaction. In the left panel, they sit close together on a sofa, engaged in conversation. In the other, each is lost in inner thought, with the man sitting in a chair and the woman on the sofa. Upon prolonged inspection, we ultimately realize that a single couple is played by two sets of actors and the backgrounds are not identical, so we are seeing different sides of the room.

Another diptych in the exhibition is somewhat disconcerting, as the left panel is more dynamic than the right one. The two-scene comparison in “Actor in two roles” is meant to provoke reflection on the multiple identities that make up an actor’s life. The imagery in the left panel, which replicates a moment from an actual play, shows two multiracial groups of four women, one of them vigorously marching in place and the other reacting with gestures and expressions of trepidation. The right panel, by contrast, features a quiet encounter between two people. While the juxtaposition of the panels may generate some interesting ideas about different types of moods or theatrical genres, the left side alone is far richer in visual fortitude and layering of potential meanings, which relate to race, gender, and identity — all very timely issues.

A multi-section work that provides a greater stimulus for our imaginations is “Staircase & two rooms,” which reveals three fragmented views of the interior of a Hollywood rooming house. Aesthetically cohesive in its distribution of pastel colors and decorative patterning throughout, this intriguing triptych begs us to respond to it as if solving a mystery. In the left panel, a man with eyes shut holds the door of room 18 slightly ajar, yet it is unclear whether he is closing the door or opening it. The central scene is of a staircase just a few doors down, adjacent to room 15. It directs our eyes upward, yet we get only the barest glimpse of the floor above. In the right section, a man lounges at the far edge of the bed, as if he could easily fall off. His room is barren, as there are no pictures on the walls and the doors to his room and to either a closet or a bathroom are both closed. No single scene dominates the triptych, but each tends to instill a sense of expectation.

Similar feelings of anticipation may be experienced viewing “Listener,” the most dramatic work in the exhibition. Set in an earthy outdoor landscape, the composition centers on a pale-skinned man, his shirt off and wearing sandals, shown kneeling with his left arm extended downwards in an awkwardly stiff position. He is surrounded by five other men who are fully clothed and wear suitable shoes for the terrain, yet he is the only figure whose face is fully exposed. We can see half of the face of the man at far left, who looks out at us with an impatient expression. Another man, seen from behind, bends towards the central figure as if to offer assistance. While any number of storylines might be imagined, the composition may plausibly be understood as a morality tale showcasing three different archetypes for human behavior: those who are vulnerable and victimized, those who are apathetic, and those who care. Due to its alluring ambiguity and thought-provoking imagery, “Listener” exemplifies Walls at his best.