Continuing through March 5, 2022

Midway through Andrei Konchalovsky’s 2019 anti-heroic film “Sin,” we see the haggard, driven Michelangelo alone in his studio, caressing the marble knee of a draped statue. Pope Julius enters, demanding to see the Moses destined for his tomb, and pulling off the sheet to reveal that only the knee, emerging from the huge white stone block, is finished, he thrashes the artist. It’s actually a humorous take on artistic obsession, and if historically inaccurate, it is indicative of the seductive mystique of marble-made-flesh in classical statuary. That seductiveness has not gone away.

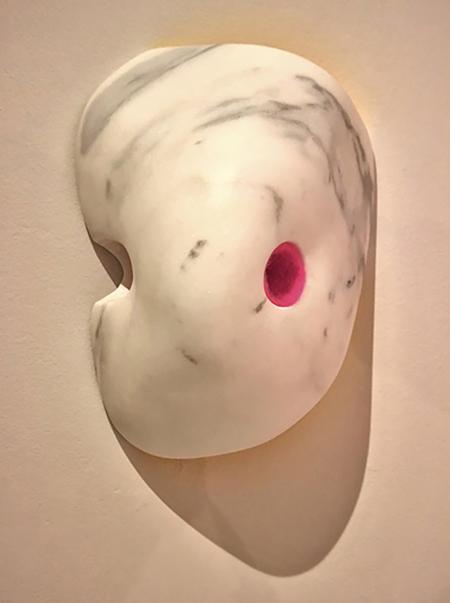

The Oakland sculptor Stephanie Robison juxtaposes polished marble, worked into Arp-like biomorphic shapes, with patches or three-dimensional shapes of colored felt that contrast humorously with the marble, suggesting, variously, fungi, anemones, foliage and even hairpieces. “Close Contact” comprises twenty-odd wall reliefs and a trio of freestanding sculptures set atop custom-made steel bases. The works, to quote her website (which features a photo of the artist happily “hugging rocks”), “synthesize and fuse: organic and geometric, natural and architectural, handmade and the uniform industrial.” The exhibit follows by a year the Portland-born artist’s “Cloud Construction,” a Christo-like wrapping of the interior space of the San Francisco Art Commission’s Grove Street Window Installation Site in white fabric. The effect was to mimic the fog banks that descend from Twin Peaks into Hayes Valley: terrestrial clouds, “seemingly innocent, perhaps even magical” that can “conceal, fog or obscure the world around us.”

Fortunately, viewers of “Close Contact” can get up close and personal to the work, as they could not with the Grove Street installation, which was visible only through the window due to earthquake-safety regulations. The one-on-one relationship with Robison’s quirky creations, which change and metamorphose as we circumnavigate them, is a joy. Robison’s allusive/elusive imagery never coalesces into a single interpretation or reading. Says Robison: “Sculpture for me is about tangibility and transformation … I have always been attracted to forms that are in direct opposition to each other or challenge their final aesthetic/functional appearance: I have intentionally carved stone to appear soft or sewn fabrics to appear rigid and architectural.”

“Heart of the Matter,” for example, appears to be a carved marble knee or elbow, but unaccountably endowed with a pink eye and a gray toupée. Move a bit to the right, however, and it reads as the head of a pensive white carp or beluga whale. “Division,” “Underbelly,” and “Niche” are vertical wall reliefs bisected by a horizontal axis or horizon line, with the felt-wrapped upper parts mirrored below by similar yet inexact ‘reflections’ in marble that anchor the lighter superstructures like ballast in a ship. “Desire” and “Spirit Rack” follow this bipartite structure more loosely, with the former suggesting the claw of a red sloth, and the latter the hybridization between an elongated heart, replete with ventricles, and a benign Edward Gorey creature. Two of the large sculptures, “Yellow Plague” and “Squeezing Blood from a Turnip,” take the form of blocks of white marble masterfully carved into indeterminate organic shapes suggestive of excavated dirt or mud, from which truncated roots or tentacles emerge. The tall “Merger,” with its accordion-bellows feet and cactus-pod head, is more overtly anthropoid, a descendant of de Chirico’s ironic, disquieting muses from a century ago.

Robison’s mastery of materials combined with her impeccably ambiguous humor may be seen as continuations of raucously iconoclastic Bay Area Funk Art, but her vision is generationally distinct, demonstrating anew that fresh, original art is possible even in the often-derivative Crazytown of the digital-era art world.