Continuing through March 21, 2022

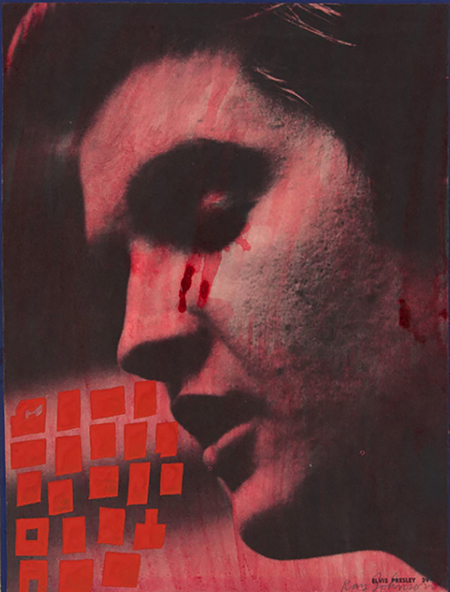

Ray Johnson is said to be the father of mail art. Certainly he was the dean of the New York Correspondence School, a fictional entity he formed in the 1960s that functioned as the conceptual platform for his lifelong project. In its name — often using stationery nabbed by a friend from the (real) New York City Department of Housing and Buildings — Johnson mailed postcards, collages, assemblages, letters, and boxes containing weird stuff to friends and fellow artists. In so doing he completely circumvented, one might say subverted, the New York City art establishment. His circle of contacts returned the favor and corresponded with one another as well, thus constituting Johnson’s “School.”

Over one hundred of Johnson ’s works, along with archival material compiled by his curator friend Bill Wilson, comprise an ambitious and absorbing show. But the experience of viewing it is oddly frustrating. Most of these pieces were made to be in motion — Johnson’s name for them was “moticos” — traveling through the postal system to arrive as a surprise gift in someone’s mailbox. Sometimes the gift inspired a return gift. This process was the art as much as, or more than, any individual object was.

Much of the work on display here is text, often documenting simple social interactions. For example, a survey Johnson mailed to his friends posed questions like “When I Visited Ray Johnson He Was Wearing ______ .” (Some wag filled in the blank with “Ray Johnson’s clothes.”) Another text piece is a typewritten list of “Famous People and What They Had to Say About Ray Johnson’s New $30 Motorcycle Jacket.” John Cale is quoted: “I like it.”

This language-heavy portion of the show reads as a thought experiment, a work of autofiction in which the artist tells a story about the world with himself as the main character. No discernible border exists here between truth and fiction, images and text.

The genius of this, but also the problem Johnson poses to curators, even now, is that these works defy art world conventions. There’s no way to monetize work like this, or even a good way to show it. On public display, it loses its intimacy. Ideally, it’s one postcard, one viewer. Maybe the guy who receives it shows it to a buddy or sticks it on his refrigerator. Or if the postcard instructs him to deliver it to someone else, he’ll give it away, or forward it to a distant colleague. The work was made to be experienced privately, maybe while standing in a dimly lit hallway at a bank of mailboxes. Imagine the little jolt of pleasure, receiving one of these missives. Often a receiver was inspired to send something back, activating a gift economy that exists entirely outside the art market.

Mail art can be understood as an act of communication or expression or performance, but never as one of commerce. It’s born of equal parts art and prank, along with the human wish simply to make contact. Nobody makes a dime off it, at least until the artist dies and dealers step in. Putting Johnson’s work on display in a museum, especially his collages, encased in their identical frames, feels like pinning butterflies to a board.

Johnson’s work is entirely of an era that no longer exists, a time when mail was physical and people actually went to their mailbox every day hoping to receive some interesting personal item. People wrote letters to each other, sent postcards, not as art projects but just as a way to keep in touch. It was an era of actual correspondence schools such as The Famous Artists School, which advertised on the back of magazines and matchbooks. Johnson’s version was both parody and homage.

In a way this show is a wonderful time capsule. But it strikes me as more than art history. One of the contradictions and also lessons of Johnson’s postcards and collages is that art will find a way around calcified structures. It reminded me in some ways of the early uses of the Internet and social media, with its vast, disorderly, and unreliably autobiographical hodgepodge of words and pictures. In some ways both offer platforms from which anonymous opinionators can shoot off messages. Both are self-edited egalitarian mediums with no real gatekeeper. Anyone could join and play. Johnson even invented several fictional galleries to show his work.

The difference of course is that, while social media constitute a very public platform, Johnson’s oeuvre reflects a singular, inspired sensibility with a dark preoccupation, death, at its core. Randomness for Johnson was a strategy, not a goal.

The other difference, and this is where the inevitable qualitative comparison must be made, is that Johnson’s work pleases with its gorgeous tactility, unlike the sensory desert that is the Internet. My favorite part of the show is the open table in the back, piled with boxes that Johnson shipped his gifts in. It’s an altar to fetishized mundanity. Enticing views of some of his packaged gifts peek out: rows of toilet paper rolls, peanut butter jar lids, fishing lures. Nothing is under glass here. It’s all just wildly present in the viewer’s space, protected only by a motion-activated alarm that goes off when you lean too close. I set it off twice.

This show is a plea for curators and the public alike to get out from under the sterilizing effects of conventional exhibition practices. It made me think of Robert Smithson, who famously said that the art world is an apparatus through which the artist is threaded. Johnson refused to be part of that apparatus in life. In death, he has no choice.

So, while I love being able to see Ray Johnson’s droll and sometimes beautiful work, this earnest presentation does not feel ideally representative of its intentions or character. Better would have been to save the exhibition costs and instead spend it on xeroxing, brown envelopes, and postage, and mail a facsimile of each piece to some unsuspecting person, with instructions, of course, to deliver it to someone else.