The 1962 Cuban Missile Crisis was actually preceded by a decade of nuclear brinksmanship. President Kennedy was narrowly elected in part thanks to his essentially groundless suggestion that there was a “missile gap,” and that the U.S. was on the short end of it. While untrue, it led to much more serious arms negotiations rooted on the premise that a détente was far better for both sides than the destruction of most essential infrastructure and the deaths of tens of millions. Most Americans understood that we were powerless to do much other than listen to the news, and for nearly two weeks many resigned themselves to imminent immolation.

The Baby Boomer generation has now lived through three major periods of nuclear threat. For younger generations now experiencing the brandishing of nuclear war by a lone maniac, welcome to our anxiety-saturated world. Please do not retreat beneath your desks. The decades-long confrontation of the Cold War, interwoven domestically with the Vietnam War and the Civil Rights Movement, gave rise to a virtual industry of protest art, literature, music, and film. The outpouring was not new, nor has it abated in the more than half-century since. But it has fluctuated and evolved. More importantly its mass of imagery, critical and acerbic as it is, has been a major factor in preventing the worst from happening. Until now there has been no repeat of October 1962.

The young Bob Dylan’s talent as a songwriter was accelerated by his personal moral resentment over the nuclear sword of Damocles then (as it turned out) shared by millions of other outraged kids. It produced “Masters of War,” “The Times They are A Changing” and other remarkable songs expressing the helplessness that at times has given way to a broadly felt passivity. These and other songs and musicians offered an emotional gateway for taking action by young people who never had. Less remembered today is Barry McGuire’s edition of P.F. Sloan’s “Eve of Destruction,” but in 1965 its impact on that demographic was of no less magnitude.

If you were paying attention to visual art, film, and literature at the time and not so very long before, the emergence of dystopian narratives was still infrequent, and therefore fresh and horrifying, even shocking in the context of the concurrent blanket of America’s post-war self-absorption. You could always retreat to your Hula Hoop.

With “Brave New World” (1932) British author Aldous Huxley set the pre-nuclear bar for envisioning a dystopian society based on the then latest developments in psychology and biology twisted for the political purpose of social control. The term “Orwellian” became lodged into public consciousness via George Orwell’s “1984” (written in 1948, Orwell settled on the title by reversing the last two digits) and has yet to be dislodged. These days we hear the term applied to the greatly enlarged environment of disinformation more often than ever. Walter M. Miller Jr.’s “A Canticle for Leibowitz” (1959) was the most reflective and moving treatments of a world slowly recovering from the setback of nuclear war — only to slip back once again.

The youth movement of the 1960s, having been very much galvanized by such books and music, channeled an activism that could not wait for post-graduate degrees. It succeeded in casting a constant eye onto the actions and policies of the leaders of the Free World, as the Western alliance called itself. If the adults who lived through the era of two world wars and a major international depression tended to admire this generation’s idealism, dismiss its naivety, or despise its experimentation, the motivating effects of the words and images of artists, many themselves still in their 20s, were undeniable and ushered in a level of accountability, often by not always accepted by choice, that no prior generation of political leaders had ever had to answer to. Might 1962 have produced nuclear disaster, or the Vietnam War that followed led to a full regional genocide otherwise? That they did not is a compelling enough answer. But reflecting on that past is not the same as having been there. The visceral moment we are experiencing today serves as an ample reminder of that distinction. The obvious comparisons to the earlier crisis, however, provide clues not answers.

Although the movie industry generally sweeps up new cultural impulses from behind, once picked up the cultural impact often grows exponentially. Sometimes this comes too late or to the wrong effect, but feature films and TV series supply a unique amplification, which can sometimes be all to the good, but sometimes not. Some of our most talented filmmakers compressed their own nuclear fear and rage into homilies dressed up in satire or drama, most notably in Stanley Kubrick’s “Dr. Strangelove” (1964), or the ensemble compilation of “On the Beach” (1959). Perhaps the most determined effort to present the lived reality of not only the immediate impact but the radiation aftereffects of a nuclear attack appeared in “Testament” (1983).

Visual art produced its slice of the cultural leadership pie that contributed to the project of accountability. Pop Art, Earthworks, Minimalism, Conceptualism, Assemblage and Light and Space formed a solid cultural core during the 1960s and early 70s that for the most part favored its rapidly expanding universe of formal and media-based innovations. It’s not that Andy Warhol, Robert Rauschenberg, Eva Hesse, Ana Mendieta and others mostly avoided introducing political elements. Fluxus and other more politically motivated movements reflected impulses in the art world that had been incubated by earlier avant gardes. Only occasionally did these artists break through beyond a devoted following within the larger art world. Joseph Beuys and Yoko Ono, for instance, both sought to strip away the emperor’s clothes and ritualize our response to the world’s knotty problems and failures. They also took their political intentions dead seriously. George Herms’ assemblage work has always striven to incorporate traits of good-natured humor and feelings of appreciation with powerfully formulated social critique. Herms sums up his aesthetic mission succinctly, “I turn shit into gold.” The reference to alchemy is not accidental, nor is it easily understood in comparison with film and music.

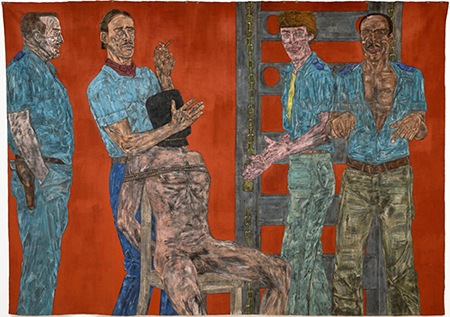

Far better known in Japan that in the U.S., the Japanese artist couple Toshiko and Iri Maruki spent more than 30 years creating a cycle of large panels memorializing the human effects of the Hiroshima bomb, perhaps most vividly in “Fire” (1950). They were witnesses to the aftermath, traveling to the bombed-out city, still loaded with radiation mere days after the explosion, in order to assist survivors. This cycle transcends the suspect tropes entirely, the focus instead on the people who survived as victims of the explosion, done in a style that is both effectively reportorial and deeply emotional. More recently, similarly skilled figurative specialists Leon Golub, with his depictions of political abuse, and Alexis Rockman, whose visualizations of ecological degradation are expert amalgams of lush paint handling adding up to scenes of savagery and devastation, have enabled us to see what in words alone remain too flat, too abstract to fully grasp. Today visuals from around the world enable us to connect far more personally and empathetically than when we had to rely on the printed word alone. Generational talents such as Mark Bradford, Banksy, Lauren Halsey, JR and others are taking all of this to a new level. But that is a fit subject for another day. We have time. Even radio has been around only one century, electricity not even two, personal computers about 40 years. We are still quite new at this.