Continuing through August 1, 2022

Bibiana Suárez looks at branding with a critical eye, paying particular attention to the visual marketing of Hispanic/Latinx food products. Her current exhibition, “De: Lata (What Gives Us Away),” addresses the depictions of women on food packaging, their images often put in service of evoking “authenticity,” exotification, nostalgia, and tradition to prompt a purchase. Suárez’s works here are Pop in style, embracing the formal aspects of her subject matter, though her representational prowess is also evidenced in the individualized portraits of real women placed where their fictitious counterparts would have been.

The works in “De: Lata” contrast with the stereotype of the kitchen as a woman’s domain, a canard still embraced in food brands’ marketing strategies. The sitters in Suárez’s pieces highlight all manner of careers and life stories: Poet Juana Iris Goergen; artist María Martínez-Cañas; educator and researcher of Latinx LGBTQ+ communities, Lourdes Torres; Gladys Rosa-Mendoza, a designer and visual strategist; painter Cándida Alvarez; and a trio including Dolce Orocio, Antonia Marroquín, and the artist’s sister, Marinés Suárez, women whose unique personal histories are captured in the compositions of their portraits.

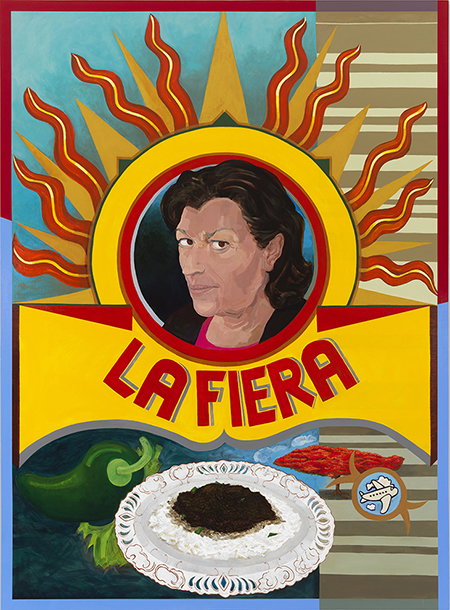

The exhibition text by Olga U. Hererra, PhD. explains that Suárez’s sitters collaborate with the artist on their likenesses. With such agency, the resulting paintings feel free of the confines of the male gaze. In “La Fiera (Untamed),” María de los Ángeles Torres, the distinguished professor of Latin American and Latino Studies at the University of Illinois at Chicago, is not smiling, submissive or particularly welcoming, unlike the illustrated women from the food packaging. The professor seems to regard the viewer sideways, her mouth set firmly, her eyebrows arched skeptically. Her authoritative gaze is powerful, effectively nullifying the issue of objectification. Torres doesn’t invite you to look at her so much as she dares you to. And while this portrait and the others are indeed breaks from the stereotypical relationship between women and food, Suárez puts imagery of food to a different use: to symbolize aspects of her sitters’ histories or characteristics. Below Torres’ visage is a Seder plate topped with rice and beans, combining her Cuban heritage and the Judaism of her family.

There is one piece in “De: Lata” that does not contain a representational female likeness, and it is Suárez’s own self-portrait. “La Suárez (Gandulera Rubia)” (2005-2011) is the earliest piece in the exhibition. It is an inkjet print on aluminum, making it the work that most closely resembles the kinds of graphics the artist scrutinizes. A photograph of pigeon peas (used in arroz con gandules, Puerto Rico’s national dish) is emblazoned with the artist’s surname, as well as her date of birth and her “net weight.” In the presence of Suárez’s recent portraits, this piece seems particularly wry and ironic, with Suárez “marketing” herself like something to be consumed. Simultaneously, “La Suárez (Gandulera Rubia)'' is imbued with declarative power, asserting her physical existence with the irrefutable facts that ground her as a flesh-and-blood woman, not some formulaic cliche.

Complexity is key throughout the works of “De: Lata.” Suárez peppers these portraits with plenty of blatant visual cues that speak to her sitters’ stories: the black Puerto Rican flag on Rosa-Mendoza’s shoulder; the photo corner that denotes Martínez-Cañas’ profession; the airplane in Torres’ canvas signifying Operación Pedro Pan. However, there are just as many cues that would evade us, if not for the artist providing some explanation. The image of a dry cleaner’s hanger recalls the place where Suárez and Orocio first met. Rosa-Mendoza’s space suit symbolizes her mother’s childhood ambitions for her. As much as Suárez has “branded” each of these women in a manner that celebrates their accomplishments and individuality, the ambiguous clues serve as a reminder that a woman’s biography is not something to be consumed in its entirety by whomever wants it. There is also tremendous power in details kept intimate.