“I think art is boundless. Art has no horizon.”

— Carlos Villa

One of the few positive aspects of the pandemic’s disruption of business as usual has been an increased focus on significant but undervalued local art heroes. Carlos Villa (1936-2013), a painter, sculptor, performance artist, poet, teacher (at the sadly shuttered San Francisco Art Institute), activist/organizer, mentor, and curator is one of them. His work melded modernist style with aspects of Filipino culture. Two concurrent retrospectives of Villa’s five-decade career are belated but unprecedented tributes to a San Francisco native son who grew up in the downtown Tenderloin district.

“Worlds in Collision,” at the Asian Art Museum, examines Villa’s emergent work of the 1970s and early 1980s. His early career was steeped in mid-century Modernism. After art school Villa spent five years in New York, making minimalist sculptures (perhaps partly influenced by his cousin, shaped-canvas abstract painter Leo Valledor). Returning in 1969 to the San Francisco Art Institute — his GI-Bill alma mater, where he would teach for forty years — Villa discerned the limits of aesthetic formalism and, reacting to one of his art teacher’s off-handed proclamation that there wasn’t any Filipino art history, embraced his Tenderloin ghetto background and culture. Out of this he evolved a hybrid style combining conceptualism and multicultural ethnic populism; that style now looks prescient as the American art audience and mass culture have become more diverse and non-white.

Villa’s adoption of a kind of modernist-inflected primitivism produced an alternate universe in which ancient and modern collide and merge. In this dimension, indigenous cultures survive, instead of having been forcibly “civilized and Christianized” (to use President McKinley’s euphemisms) by aggressive capitalist empire-building. Three ink drawings from Villa’s “Tatu” series (1971) embellish Itek photocopied photographs of the bare-chested young artist with improvised geometric patterns. These may not exactly replicate Melanesian body decoration, but they do exemplify the artist’s “recuperative strategy” of “reinvention” in the wake of his “ghettoized” childhood. Villa believed that his art’s utang — Tagalog for “tribute” — might spare younger artists his generation’s struggles for respect.

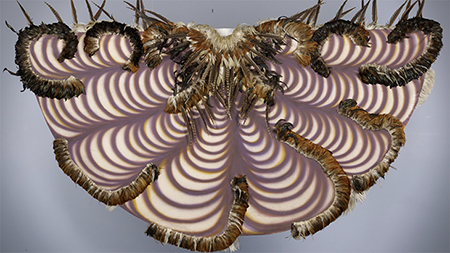

The priestly cloaks and capes that Villa created in the 1970s are probably his best-known works, and they are still stunning. Combining raw, unstretched canvas, sweeping whorls of airbrushed acrylic paint that imitate plumage, and sewn-on materials such as feathers, bone, rags, teeth, nails, twine, and beads, these garments evoke African or Oceanic religious rituals. With “Ritual, My Roots, Painted Cloak, Perfume, and Third Coat,” the artist became both creator and curator of an imagined religion and spiritual practice.

Three feathered works posit sorcery-powered transformation and flight, either literal or metaphoric. “Artist’s Head with Bone Dolls” is a handmade paper self-portrait, suggestive of a ghostly mask that induces trance-travel. “Artist’s Feet” calls to mind kurdaitcha, the feathered shoes of Australian shamans that are said to render the wearer invisible. In Villa’s hands they also hark back to Greco-Roman talaria, the winged sandals of Hermes or Mercury. “Untitled (Arm with Feathers),” another Itek/ink drawing, depicts an outstretched invisible arm bedecked with real feathers and drawn talons.

While the Asian Art Museums’s exhibition focuses on magic and mystery, the Arts Commission Gallery show, “Roots and Re-Invention,” curated by Villa’s friends and colleagues, Trisha Lagaso Goldberg and Mark Dean Johnson, draws from the more social and communitarian work of the 1980s and 1990s. Reflecting Villa’s belief that “art actions could be as viable as art objects,” the works here are concordant with the wider options available to artists once all the disciplinary and media barriers were breached with the acceptance of installation, performance, and conceptual art.

Villa’s work also benefited from his own need for aesthetic freedom, i.e., not to be a gallery’s “trained monkey” and not to fall into the “crab box mentality” of competition that he had observed at times among the unmarried, underpaid “bachelor uncles” (manongs) of the preceding generation of itinerant workers.

A Giacometti inspired sculpture, “Surrender Monkey” (1988) suspends the disarticulated limbs of a rubber monkey inside an implied vitrine (actually two intersecting metal rectangles). The title refers to racist epithets used by American soldiers against their supposedly unworthy and subhuman enemies. A 1996 two-panel assemblage made from found doors covered with black feathers, “American Immigration Policy (Diptych)” is an elegiac commentary on the exclusion of Filipinas from 1899 to 1946, based on the doorways of the single-room occupancy hotels where isolated laborers lived.

The exhibition showcases Villa’s wide range of interests and approaches, featuring black door panels painted with schematic apertures juxtaposed with Panama hats mounted just above center. There are black feathered paper sheets with family funeral photographs. Aluminum/wood geometric abstractions are part of the mix. To gestural abstractions on unstretched canvas Villa adds sewn-on chicken bones, and in one the imprints of the artist’s painted body. A body cast adorned with feathers is seemingly half-submerged in its oval base. A performance of a 1980’s shamanistic ritual was recorded on video when video was a cutting-edge medium. Then there was his use of family photographs grouped under various categories, with poetry or informative inscriptions added for context, including a triptych of the same group shot of baby Carlos’s christening, June 12, 1937.