Prinston Nnanna’s debut solo exhibit both perpetuates a deepening school within contemporary African-American art — mystical Afro-Futurism — and branches out into a more earthbound, but no less hallowed and projective world of fantasies and rituals. What is it about both contexts that influences Nnanna’s depictions of the most mundane personal or communal events like an ice cream cone or a haircut, and renders hieratic and coldly Egyptian otherwise passionate moments of intimacy and encounter? The question is partially answered by Nnanna, a Houston native now living in Brooklyn, a product of Texas Southern University and former student of Robert Pruitt, who is only beginning what will hopefully be a sustained investigation of these very themes.

From childhood wisdom gained through anguished experience, through hesitant adolescence expressed in attire and haircuts, and on to early manhood complexities over education and one’s role in society, Nnanna is carving out subject matter territory like a brilliant novelist starting with short stories out of which a larger narrative is built.

The camera plays an important role among Houston’s Afro-Futurists, but with Nnanna, time is broken down into dragging increments of models sitting, their identities captured, psychological eye contact with the viewer carefully engineered yet classically expressed. Varied surface treatments on paper provide pleasure for the roving eye. Each story unspools, as in “Grandpa Gave Me My First Haircut,” which dips into the faded, gold-toned pages of a private family scrapbook. Color is always the least important formal element, but it is deeply symbolic, as in the pink of the kaftan in “Gloria,” or the red-and-blue eight-pointed star emblem on the back of a robe in “American Dream.”

Passages of the ubiquitous gold washes are sometimes smudged with charcoal, the ultimate luxury put-down, so plentiful is the alchemical, transformative color of gold. Sitters are in possession of situations, like the little girl in “Stacks” who reads and defies judgment with her pointing chin; cooperating with the artist in “Waiting on Judgment Day Study;” or posing for an enigmatic allegory in “Where I Fit In,” with its upside-down book cover stamped ‘Holy’ and perched on the sitter’s head. Time is fatigued, defeated here, but with faintly hopeful expressions intensified by the Byzantine gold effect and the monumental treatment of the banal events of community. Nnanna’s subjects may live in peacetime, but one with an implied backdrop of street crime and poverty.

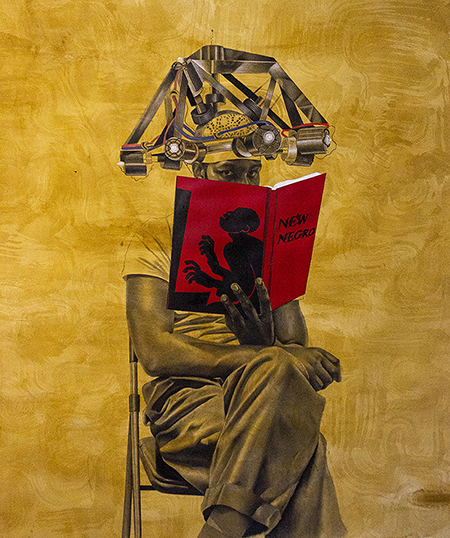

“Black to the Future” more explicitly summons up the Houston Afro-Futurist vibe. Wearing an elaborate see-through metal-and-LED headdress instead of a space helmet, it is a self-portrait of the artist reading a copy of “The New Negro,” Alain Locke’s legendary 1925 Harlem Renaissance anthology. Enrobed in gold, ready for his close-up, the sitter is too absorbed in literature to be distracted, but still vulnerable to alien attack. Accordingly, Nnanna has updated the book title to “New-est Negro.”

The women and girls in “Gloria,” “The Original Candace Goodnight,” and “Stacks” constitute an intergenerational clan of their own, like the heroines in a Gloria Taylor novel or a Tyler Perry film. The men are more formally isolated in compositions that emphasize tight, mug-shot close-ups. They function as operatives in a Nnanna’s intersecting collective narratives, like the Afro-harlequin-suited jester in “You Will Be Called, Pontius, Because You Rely on the Judgment of Others,” with its accusatory, Baptist-pulpit title, damning the man who damned Jesus to the Cross. More acutely current is “Where I Fit In,” depicting the seated front of a book-capped youth, his eyes averted, ending the exhibition on the question stated by its title: “Where do I Fit In?” And where exactly will that be, the country I live in or a futuristic world of peace and justice only attainable in studio fantasies for the price of a ticket to outer space? Despite all the harrowing implications of Nnanna’s glimpses of tales and stories, there remains a strong sense of what others have called unexpected or unwarranted optimism. What we see expressed here is radical hope.

The largest (50 by 80 inches) and most promising painting here is “Thanks … giving,” which also is the most dispersed composition. Five “plot elements” float in a palace of servants (white) and masters (an African princeling). All are set before a royal golden curtain. While a butler presents a Benin bronze headdress on a platter (metaphorically referencing colonialism’s genocides), the young child is given a haircut beneath a cloth skullcap. As if in further reversed obeisance, the butler conceals another carved head behind his back, part of the endless flow of cultural masterpieces out of Africa that are only now being returned to their original patrimonial homes. To retain this richness of meaning with such economy of means is challenging indeed, but Nnanna is up to the task.