Continuing through October 22, 2022

Kelly Berg expresses a faithful optimism in humankind’s chances of survival with a series of captivating paintings inspired by a number of artist residencies and other travels that involved hiking through rocky terrains in Southern California, Hawaii, and Italy. This, of course, is in light of the threats to the planet posed by climate change and the destructive natural phenomena it has begun to bring about. Based on her personal observations experienced living in earthquake-prone California, as well as on visits to several volcano sites and to the Giza Pyramid complex in Egypt, Berg has painted dramatic and luminescent landscapes dominated by pyramidal or triangular structures. These are integrated into natural settings featuring mammoth rocks, the aforementioned volcanoes, and, in one instance, the ocean at high tide. Mostly viewed from slightly overhead, as if photographed by approaching drones, the imagery is rendered in sepia-toned and blue-tinted palettes traditionally associated with vintage archaeological photography, in striking contrast to the brighter yellows, oranges, and purples of Berg’s earlier paintings (which also employed kitschy sculptural appendages).

Considering the spiritual overtones Berg brings to the new paintings via the symbolic representations of pyramids, the haloed sun, and bursts of intense light, the move to a more straightforward presentation is appropriate and effective. It both brings clarity to Berg’s vision and places her new work in the historical framework of 19th-century American Luminism and 20th-century Transcendental Modernism.

In two of the larger panoramic canvases, Berg builds upon memories from a 2019 artist residency in Naples, Italy, where she had a view of Mount Vesuvius from her studio. In “Light of Vesuvio,” the focus is on the center of the composition, which is dominated by a dormant volcano and, superimposed over it, a partially transparent Napoli obelisk that runs through its center like a spine. While dark clouds fill the surrounding sky, the obelisk emits a flame-like light from its tip, reminding us that, although the volcano has not erupted since 1944, it will again.

Nevertheless, Berg considers such natural disasters within the larger scheme of a divine universe, an idea that she expresses by overlaying the composition with interlocking triangles that call attention to the geometric substructure of nature, the divine proportion known as the Golden Section triangle, and the Modernist tradition of representing spiritual concepts with abstract geometry.

Three locations in the Bay of Naples — Mount Vesuvius, the Isle of Capri, and the Isle of Ischia — are barely visible across the waters in the distant horizon of “Tunnel through Time,” where the central image is one side of a pyramid with a Romanesque arcade running through it, mostly below sea level and superimposed over piles of rocks. Although Vesuvius is shown erupting at upper left and the Isle of Ischia is enduring a severe thunderstorm at upper right, the destructive forces of these natural catastrophes are dramatically countered at center by a mystical light that rises up from the deep recesses of the arcade like a Barnett Newman zip, infusing the Isle of Capri with a divine presence.

Berg examines the dichotomy of turbulence and calm in two smaller canvases shaped like inverted triangles. Each houses images of pyramids integrated with volcanoes the artist visited in Hawaii and Southern California. Viewing “Heart of the Earth,” we become witnesses to a fiery explosion of the Kilauea Volcano on the Big Island of Hawaii, the most active volcano in the island complex, having erupted as recently as 2021. The painting’s warm sepia palette conveys the feverish temperament of the fire and billowing smoke that obstruct our view of a distant pyramid, itself backlit by flames.

By contrast, Berg employs cooler bluish tones to portray the dormant cinder cone volcano at Amboy Crater, located in the Mojave Desert. As with “Tunnel through Time,” this painting leads the eye on a visual progression that begins in the lower center foreground, where we peer over the top of a pyramid and then venture along a winding road towards the quiet crater that is forcefully silhouetted by an intense burst of light, another pyramid, and the radiant sun above. The concept of a spiritual journey conveyed by this sequencing recalls the similarly metaphoric structuring in the most moving paintings of 19th-century German master Caspar David Friedrich.

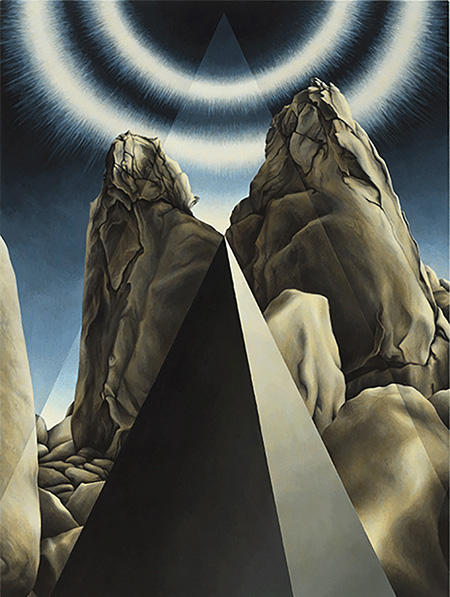

While Berg’s paintings reveal an acceptance of the yin/yang principle and belief in the cycles of nature, two in particular display her hope for what lies ahead. During a residency in Joshua Tree, Berg photographed pyramidal mirror sculptures that she set up temporarily in the outdoor landscape. Although three of the photographs and one sculpture are included in the exhibition, it is in the paintings “Monuments of the Future Past” and “Illumination at Giant Rock” where Berg’s ideas fully crystallize. In both, pyramids and the desert’s giant rocks and boulders are saturated with supernatural-looking light that emanates from the sun with a halo effect. In the former, the sun appears to be so powerful that it has two rings of light enveloping it. In the latter, it causes a spark to occur on the surface of a boulder, as if something miraculous is taking place before our eyes. Just as the ancient Egyptians worshiped the sun as a divine source of life, Berg calls attention to its restorative powers which, in practical terms, lie in the potential of solar energy to repair and heal the planet.