Continuing to December 10, 2022

Man Ray, Alfred Stieglitz, Ansel Adams, Richard Avedon, Robert Mapplethorpe — what do these great photographers of the 20th Century have in common? Remarkably little, actually, except that they used cameras and were male. It is the historical male domination of the field of photography that Jordanna Kalman zeroes in on in her insightful exhibition, “Jordanna and the Masters of Photography.” Kalman, who is based in upstate New York, conceived this series in response to a call for submissions by The Yellow Rose Project, a curatorial initiative commemorating the centennial of the ratification of the 19th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, which established women’s suffrage. Contemplating the long struggle to gain voting rights for women, Kalman began to ask herself which areas of her own life she felt most disenfranchised in, and at the top of that list was her chosen art form and the hegemony of male perspectives and narratives over it. The photographs she created for the project sought to address and, at least on a personal level, to redress that dominance.

From this originating impulse Kalman assembled a powerful and varied body of work, utilizing a range of formal approaches. Most prevalent among these approaches is the conceit of inserting photographs she has taken into windows cut out of reproduced images by iconic male photographers such as Edward Weston, Kenneth Josephson, Emmet Gowin, and Garry Winogrand. Some of the superimpositions are thematically straightforward, others more obtuse. Many reference the perennial dynamic of a male photographer regarding a nude female sitter, with all its inherent inequality.

Kalman’s modus operandi is to bring attention to and then subvert the male gaze. For example, over a Gowin nude — reclining on rumpled sheets, eyes cast dreamily at the ceiling as if in post-coital bliss — Kalman inserts her own resolutely unglamorous photograph of a woman standing in a shack wearing a nightshirt but no pants or underwear, her legs spread wide nonchalantly as she pisses on the wooden floor. There is an incongruity, a parodic bathos, in the contrast of gauzy romanticism with a cold-eyed documentation of urination only a fetishist would find arousing. In another piece, Winogrand’s photo of men at a strip club ogling a nude dancer is counterposed with a macro shot of a praying mantis, an insect known for its females’ instinct to devour males following copulation. The allure of the burlesque dancer, celebrated as a pagan goddess by Camille Paglia in “Sexual Personae,” plays against both the tawdry venue and the fierceness of the mantis’s mating rite.

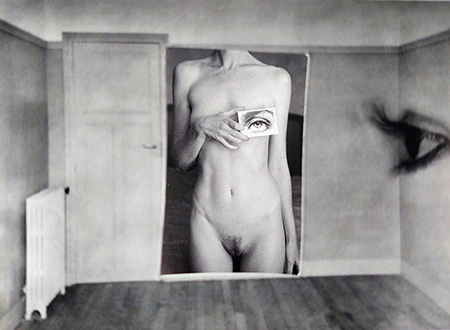

The issue of countering male biases with a female gaze, which Kalman calls “a condescending, pigeonholing term,” is hardly as simple as reversing the lens on male subjects and objectifying them as they have objectified women (a trope trotted out periodically in exhibitions that traffic in beefcake pinups or gender-bending imagery informed by queer studies). Many of Kalman’s works collage women’s eyes over photos taken by men, literally appending a product of the male gaze with a picture of a female eye gazing — a visual pun as well as a conceptual statement. She alters a Maurice Tabard image of a model holding a photo of an eye over her breast, perhaps alluding to the systemic voyeurism women endure in a culture of catcalling, Peeping Toms, and pornography.

In a nine-piece photomontage, “how to,” Kalman places cut-out photos of breasts over cloudscapes, as if referencing the mind/body dichotomy and the madonna/whore complex: celestial perfection in opposition to the corporeal crudity of disembodied cleavage; and the sexist expectation that women embody both. The misogynist demand to serve dually as objects of lust and wholesome maternity also informs a four-piece installation based on images by Walker Evans and Paul Strand, with Kalman’s nudes inhabiting the space between Corinthian columns, a picket fence, and a room appointed with signifiers of domesticity: a broom, a dish towel, a frying pan. This is the paradox imposed on women, to be put on pedestals but also to sweep the floor.

There is a wry, knowing wit in most of these superimpositions, which, despite the earnest subject matter, keeps the show from turning overly pedantic or polemical. By adopting a pictorial gaze that is simultaneously inward and outward, reflective and satiric, Kalman highlights the absurdity of elevating women into Platonic ideals while subjecting them to systemic dehumanization. Her use of the cut-out window succeeds as a visual as well as conceptual framing device, contextualizing her work literally within canonical works from the male pantheon.