Continuing through December 3, 2023

For some 40 years, Earlie Hudnall Jr. has been photographing people going about their daily lives in Houston’s inner-city African American neighborhoods. His hand-printed gelatin silver prints range from intimate portraits of mothers and sons to children playing in the street, from lovers dancing in a jazz club to an old man smoking on his porch. These photographs focus on what we all have in common — our humanity — rather than on the disparities and challenges that exist in these communities.

This exhibition was organized to honor Hudnall as this year’s recipient of Art League Houston’s biennial Lifetime Achievement Award in the Visual Arts. His father was an amateur photographer in Hattiesburg Mississippi, who documented key events in the family’s life. His grandmother lived next door, and Hudnall was fascinated by her album of family photographs and newspaper clippings. He took a small camera with him while serving as a marine in Vietnam, documenting fellow soldiers. After enrolling at Texas Southern University, Hudnall was recruited by Dr. Thomas Freedman, the head of the debate team, to document the university's Model Cities Program. This assignment sent him into the heart of the city’s historically Black neighborhoods. The experience was powerful, as these impoverished communities reminded him of his own upbringing in Hattiesburg. After graduation, he worked freelance until 1979, when he was offered a full-time position at TSU as staff photographer, where he remained until his retirement.

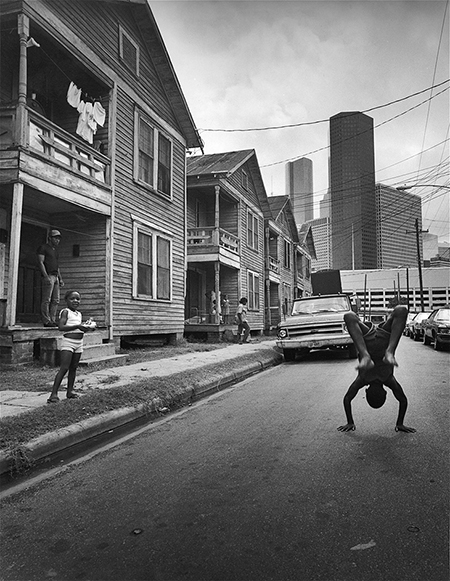

The 33 black-and-white prints on display were taken between 1973 and 2020, with the majority dating from the 1980s and 1990s. During this time, Hudnall was fully realizing his vision and creating some of his most iconic images, in particular “Flipping Boy” and “Looking Out.” He was especially drawn to adolescents and elders, the former conveying innocence and the latter dignity and pride.

“A unique commonality exists between young and old because there is always continuity between the past and the future,” Hudnall said. “The camera really does not matter — it’s still just a tool. What is important to me is the ability to transform an instant — a moment — into a meaningful, expressive, and profound statement — some personal, some symbolic, and some universal."

These photographs are more powerful than one might expect from their 16 by 20 inch format. Hudnall moves in close until his subjects fill the frame, which eliminates most distractions. “Dr. T.F. Freeman and Dr. M.L. King” portrays Dr. Freeman silhouetted below a sculpture of Martin Luther King Jr. He strikes a thoughtful pose, his hand cupping his chin, while MLK faces the opposite direction, his robes swept by the wind and his right hand raised. Shot from below, nothing else appears in the photograph to distract the eye; it’s straightforward and effective. Likewise, in “Going Home, 3rd Ward,” an older woman in a domestic uniform is shot from behind, a cane in her right hand and several packages in the other. The background is softened and blurred to focus attention on how, despite her obvious exhaustion and difficulty walking, she makes her way home alone.

Although Hudnall’s work has taken him to Africa, Belize, and beyond, his most recognized work has been realized in his home city. He does not have to go far to encounter subjects who inspire him to capture the moment with one of the two cameras he carries with him at all times. In an interview with Sarah Reynolds in 2006, Hudnall said about that moment: “That is something given to you by God, and it is the result of hard work and perseverance. It is something that is sacred and something you don’t abuse, and you don’t misuse. I have to live up to that. To do less than that is not putting forth my best effort.”