Continuing through December 22, 2022

In the 1964 Shirley MacLaine comedy, “What a Way to Go!,” one of the innocent heroine’s rags-to-riches husbands who work themselves to death is an unsuccessful American artist in Paris played by Paul Newman. After he invents a primitive robot that converts sound into paintings, his career skyrockets — until the yellow articulated arm cranes kill him. The moviemakers may have had in mind the Dada pseudo-machines of Jean Tinguely, especially his absurdist “Homage to New York” (1960), with its manic activity that mocked the capitalist human beehive.

However, after an additional sixty-odd years of aesthetic revolution and technological progress, including the omnipresence of digital culture and the looming challenge to human creativity from artificial intelligence, it is clear that machine-made art is not only on the way, but here, and here to stay.

Agnieszka Pilat grew up in Cold-War Poland and emigrated to San Francisco in 2004 to study portraiture and illustration at the Academy of Art University. Her precise but painterly portraits of machine forms (in what the art critic John Seed has termed the disrupted-realism mode) found favor with tech-industry collectors at Autodesk, SpaceX and Waymo. In 2020 she became a resident artist at Boston Dynamics, in Waltham, Massachusetts, using the company’s 55-lb. yellow robot dog, Spot, and Atlas, a 5-foot-tall humanoid robot, as models for her handmade oil-on-linen art-historical pastiches of Leonardo’s “Vitruvian Man” and Michelangelo’s Sistine Chapel “Creation of Adam” for her 2021 show here, “Renaissance 2.0.”

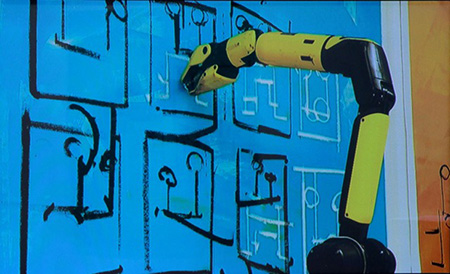

The current show of ten mixed-media paintings is entitled “ROBOTa,” a Polish word translated variously as job, chore, work, labor, work, and needlework. (The etymologically inclined may know that ‘robot’ derives from the Czech satirical writer Karel Capek’s robotnik, or ‘worker.’) The new works are not in the stylized realism of Pilat’s previous work, but abstract. What’s more, they’ve been executed by the aforementioned Spot (B22) and the green bipedal anthropomorphic Digit (B70). Pilat thus not only surrenders substantial control to her robot apprentices, but changes her aesthetic viewpoint from Renaissance realism to conceptual abstract painting.

Pilat stretches the canvases and lays down the bricky background coats of blue, orange, or pale gray acrylic, then programs the robots and equips them with black and white oil sticks to draw with. The orthogonal line and small circles suggest blueprint schematics, scaffolding, circuit diagrams, and even simplified cityscapes with tiny pedestrians, as seen by, say, Paul Klee or Jean-Michel Basquiat. Several marching-titled paintings, such as “B22 Double March Navy and Gold,” feature circular patterns of paint splotches or tracks formed by the quadrupedal robot turning on its central axis, seemingly stamping its feet, as a gallery video monitor documents.

Pilat’s titles (e.g., “B22 Selfie with a Hat,” “B70 Multiple Portraits”) give due credit to her collaborators, B22 and B70, although she notes that their ”mechanical limitations,” which make them “imperfect extensions of my arms,” paradoxically lend them character — a reprise of the modernist painters’ desire to avoid ingrained habits, facility, and thus self-repetition and parody. Says Pilat: “Through their errors, robots promise to make art interesting again — interesting for people and perhaps one day for their fellow machines.”

The robots will not balk — at least not yet — at working without commitment. But the temptations of technology (an infinity of iterations with the click of a mouse, and almost free labor) are inherent in the new, potentially vast means of automated art production. Pilat’s progress from traditional realism to robotic conceptual abstraction is extraordinary. Pilat believes that, “Machines are humanity’s children … Machines are today’s celebrities, perhaps even the aristocracy of the 21st century.” How her artistic adventure progresses within the context of our rapidly evolving culture and technology will be worth watching.