Continuing through April 30, 2023

It’s Black Lives that constitute the Matter, meaning, and message of Los Angeles artist Henry Taylor’s extraordinary survey/retrospective, “B Side.” The show’s more than 150 works of mostly acrylic painting, all figurative and portrait-based, but also includes drawings, sculptures, and an installation. Throughout the show, Taylor reveals himself to be an aesthetic force of nature, a sophisticated naïf and brilliant visual raconteur. With imaginative aplomb he prolifically chronicles the contemporary lives of both anonymous and famous African Americans alive today and from the past.

Many of the works retrieve, reconfigure, and reframe into dramatically charged images the myriad instances of injustice our Black brothers and sisters find themselves still having to endure. Others present members of Taylor’s family, friends, and acquaintances in relatively conventional, folk-art-tinged portrait poses, though consistently painted with elegant fluidity.

With a kind of insouciant transparency, the specters of the work of the many artists who have informed and contextualized Taylor’s paintings make themselves known. A short list would include Picasso, Matisse, Jean-Michael Basquiat, Bob Thompson, Philip Guston, Romare Bearden, Jacob Lawrence, Kehinde Wiley, and Mickalene Thomas. Indeed, the energy and spirit of Taylor’s art historical ensemble emanates from these works, energizing the installation the way that members of a jazz quartet weave their unique sensibilities into a unified fabric.

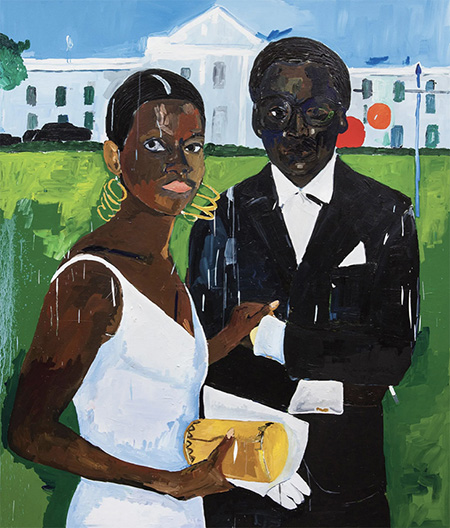

In “Cicely and Miles Visit the Obamas” (2017) Taylor joins the images of two African American cultural stars (Cicely Tyson and Miles Davis, based on a 1968 photograph by Ron Galella), with the first Black Presidential couple named but not depicted. Instead, behind the figures there looms a ghostly rendering of the White House spreading horizontally across the back width of the canvas like an opaque horizon, preventing the eyes from looking further, from finding hope. The bleached exterior of the “People’s House” pointedly clashes with Tyson’s and Davis’ brown and black skin.

Slyly, though not inconspicuously, Taylor positions a small red and orange dot directly behind Davis’s neck, seemingly pasted directly onto the White House’s fading façade. It’s a stealthy reference to late L.A. Conceptualist John Baldessari and his articulation of negative space, the occluding spheres symbolize the brutal, chronic invisibility many African American citizens still feel today — overlooked akin to the “B Side” of an old vinyl record. Davis died years before President Obama assumed office; Tyson did finally visit the Obamas at the White House in 2016, when she accepted the Presidential Medal of Freedom.

Yet a generous and ameliorating sense of humor enlivens so many of Taylor’s paintings. For example, “A Jack Move — Proved It” (2011), Taylor’s tableau of Jackie Robinson successfully stealing home plate during the first game of the 1955 World Series between his Brooklyn Dodgers and the New York Yankees, immortalizes the “Jack Move” as one of baseball’s most iconic images. Taylor paints the title of this piece directly across the top of the canvas. The ball player’s first name, “Jack” intuitively invites the word “Black” to instantly precede it. The resulting “Black Jack” doubles for Robinson’s racial classification and the casino card game.

Taylor frequently uses words as riddle-hooks that challenge us to unearth deeper semiotic and social meaning. But is the artist, by returning us to 1955, asks us to recognize then Dodger owner Branch Rickey’s “gamble” in signing Robinson to a professional contract, which famously broke baseball’s color barrier? Or is the piece admonishing us for depositing “Jack’s” courage in taking to a field full of many racist players into yet another bin of forgotten B-Sides of African American history?

The core of Taylor’s practice is grounded in personal relationships and the deep connection he feels with his family and friends. The portraits, of individuals or of groups, that Taylor renders from such bonds display a remarkable gift for painterly empathy. Some of the artist’s subjects for these portraits represent people down on their luck who live on and close to Skid Row near Taylor’s studio. His title for one of these populist portraits (the artist offers to compensate his sitters for each of them), “Emery: shoulda been a phd but society made him homeless,” once more paves a narrative leading directly into the visage of his sitter’s eyes.

One is struck by the depth of color throughout. The earth-toned, almost creamy quality of Taylor’s paint radiates with a paradoxically refreshing and youthful transparency. One fast forwards through Southern California art produced since the beginning the 20th century — turn of the century Impressionist/Plein-Air painters, Depression-era social realism, post-war Light and Space artists, the cosmic and spiritual meditative Zen seekers, the deconstructionists, social practice artists, all of whom found inspiration amidst the variegated atmospheric mana-hues of L.A. It’s all there.