Continuing through April 22, 2023

This exhibition of 16 works on paper by the late Virgil Grotfeldt was inspired by the inclusion of the artist in “The Curatorial Imagination of Walter Hopps,” currently on view at the Menil Collection. Hopps and Grotfeldt met in the 1980s, and they became close friends and colleagues. The paintings in the show date from 1992 to 2007 and reflect a period in Grotfeldt’s career following his meeting Dutch installation artist Waldo Bien in Berlin in 1990 and experimenting with the coal dust Bien gave him. The cancer diagnosis that followed in 1993 further led to a profound shift in the artist’s technique and imagery.

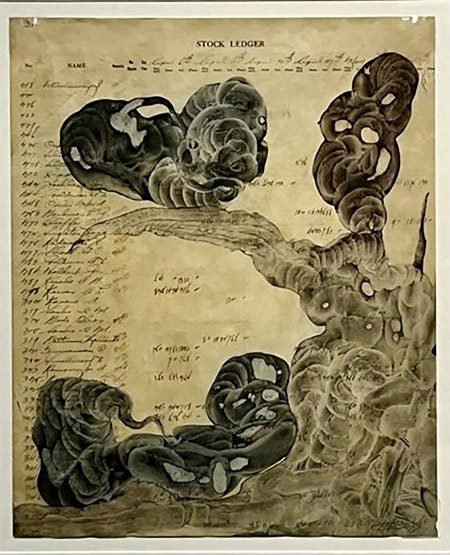

Grotfeldt began painting on various found papers such as antique ledger sheets, technical maps, nautical charts, and vintage letters. Using carbon powder suspended in an aqueous-based acrylic medium, he developed a distinctive method of creating amorphous biomorphic figures by applying monochromatic washes that range from sheer to opaque. Often referred to as dreamlike or cellular, these works on paper suggest plants, snails, and worms, as well as angelic winged creatures and sexual organs.

In “100 Fathoms” (2001), underwater birdlike forms hover above ominous segmented organisms. In “Untitled” (2007), the ocean has been transformed into a mountainous landscape that serves as a backdrop for serpentine forms. These flora and fauna are unsettling, as they suggest growing malignant cells or, as in “Untitled 776614” (2007), the plaques and tangles of Alzheimer’s disease. By painting on gridded technical maps or nautical charts, as in “Separate Elevations” (1999), Grotfeldt sets up a dichotomy of order and chaos that reflects his state of mind at the time.

Grotfeldt became increasingly interested in medicinal plants and rituals to restore harmony to the sick. According to Patrick Healy in his comprehensive book, simply titled “Virgil Grotfeldt” (2005), certain plants associated with healing began to appear in his work at this time. The artist’s technique of creating plant forms in which he pushes and swirls a loaded brush along the surface with pulsating degrees of intensity, best represented here in “Of Unknown Origin III” (2003), suggests the automatic writing of the Surrealists, who suppressed conscious control of the brush or pen in order to gain insight into the subconscious.

In the Brooklyn Rail (April 2009), Stephanie Buhmann observed, “He incorporated found letters, antique maps, and nautical charts to initiate a dialogue between conscious systems of order and the expressive freedom of the subconscious.” According to Grotfeldt, “Walter [Hopps] and I shared an interest in the subconscious self.” Another close friend, sculptor Meredith “Butch” Jack, described Grotfeldt’s work as magic realism, theorizing that “somewhere in the cosmos, all the forms he saw existed” (Glasstire 2009).

Titles such as “After Gethsemane,” “Blood Orange,” “Night Violet,” and Tracking Beauty’s Light” direct the way we respond to the images, thus referencing the physical and psychological distress and search for resolution the Grotfeldt was surely experiencing. Automatism served to penetrate these feelings and enabled him to create this distinctive and mysterious world.

The sampling of work here illustrates that once Grotfeldt established this practice of using found papers as the base for his monochromatic botanical forms and washes, he never returned to his previous styles, which ranged from hyperrealist paintings in the 1970s to enigmatic figures and faces in the 1980s. Grotfeldt was interested in spirituality throughout his career, but during the last 15 years of his life, the visual manifestation of his search resulted in a significant transformation as he delved more deeply into mysticism and symbolism in search of enlightenment.