Continuing through April 29, 2023

Ever since art photography’s heyday in the 1980s, the medium has been accepted without question as a contemporary art form. It has its own university art school major and art galleries and is accepted into virtually all major art museum collections, not to mention art centers and museums specializing in photography. However, with the advent of the internet and smart phones with cameras, the bloom came off the rose, and any argument for photography’s uniqueness has weaked. That’s why it’s heartening to see younger artists refreshing the medium’s creative potential. In their Seattle debuts Marcus Lelle and Matthew Behrend argue that photography’s potential for limitless expansion and innovation is secure.

Lelle and Behrend are early in their respective explorations of photography and, as this two-person exhibit attests, their aesthetic interests are very different. With Behrend, who has undergraduate and graduate degrees in electrical engineering from University of Southern California, the technical innovations achieved are always in danger of overwhelming the haunting and ambiguous character of his subjects. Lelle studied photography at Montana State University before returning to Seattle to take a job at the leading commercial photography portrait studio, Yuen Lui, where he is now a manager.

Building on his dissatisfaction with photography as a two-dimensional medium (“little to no physical interaction for the audience”) while still an undergraduate, Lelle’s senior thesis exhibition used what he calls “hydro-graphic” printing to set images atop one another on blank store mannequin heads. Some of these are included here. For example, among the five heads (all dating from 2016), each is mounted on the wall supported by a black metal pipe. This is the most effective use of what he now calls “water-transfer” printing to create multiple-face images on the three-dimensional mannequin head. In “Head #3” the inert male model wears a skullcap with extra black eyebrows above the plastic ones and a mustache created by a color photo overlay. Given the Muslim skullcap and the double identity, the white mannequin with its water-transfer superimposition could suggest the conflict among religious identities or the problems of maintaining traditional beliefs in contemporary society. With “Head #2,” a female face overlays a pink male face on the mannequin at an angle suggesting gender dysphoria or the pressures of toxic masculinity versus gender complementarity. More enveloped by the water-transfer print, “Head #1” uses another female image overlapping a male mannequin head with white chest and neck.

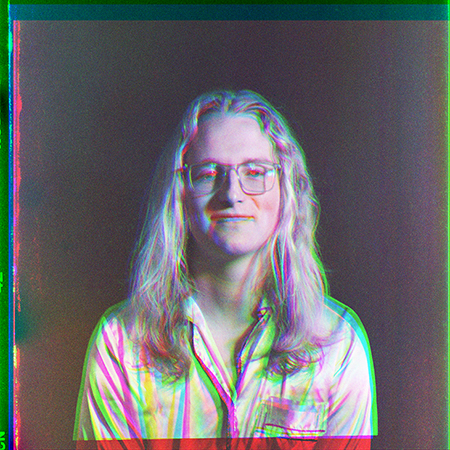

More intriguing but less innovative, three “trichromogenic archival digital prints on acrylic” are large-scale (3 by 3 feet) portrait busts of two women and a man. Each uses a black background to place the smiling sitter in a frontal pose. Blue, red and yellow films are transposed atop the base image. These suggest the flux and shifting self-creations of young people, never fully fixed or unable to change and grow. They share the fluctuating quality of the mannequin heads, especially “Trichrome Portrait 001” (all 2023), wherein the teenage girl wears a multi-striped woven sweater and has blonde floppy locks cascading over her forehead. “Trichrome Portrait 002” depicts a young man in a black tee-shirt wearing wire-framed glasses. The darkest image on view, his white skin and neck recede into the darkened background and clothing. More adventurous is “Trichrome Portrait 003,” which is perhaps a transgender woman. Her long face and scraggly shoulder length blonde hair offset a firm, jutting chin. The shirt, with its revealing neck-line, could be a blouse or a pajama top.

Behrend’s world begins from the opposite premise of Lelle’s. Instead of fighting the two-dimensional nature of photography to favor three-dimensional objects and illusions, Behrend attempts to turn three-dimensional phenomena into two-dimensional imagery, using photography as part of a panoply of tools that include “electric fields [that] are used to imprint images onto metal panels in an electrolyte bath.” They often appear more as abstract paintings than photographs, although the image source is usually photographic even when drawn from outer space, as in “Jupiter” (2015) with its full-field detail of the planet’s horizontal stripes. The most extreme in terms of vacant imagery, “Records of What Was Now” (2023) consists of light and dark orange spatters. More astronomical and convincing, “Creation Myth” (2022) sets yellow and rust above a single black oval. “Radiant Vision” (2023) and “Column Light” (2023) complete the interplanetary journey with orange columns and a black circle hovering above a U-shape, the metaphorical source of human existence in the cosmos.