The recent flurry of revelations about the artist Tom Sachs and his studio has raised many questions. As it turns out, the story is not so much about the ‘separating the artist from the art’ debate as it is the state of an art world crowned by Big Artist Studios (by which I mean populated by, let’s say, 5 or more assistants). I had a few brief part-time stints in college working for artists, but haven’t been employed by any since. Not for lack of trying: in grad school I reached out to an artist whose work I loved, but who told me he was set. I subsequently responded to a few job postings, but nothing came of them. Since then it’s become clear that this was something I didn’t want to do, a sentiment aided by what I’d been hearing from peers who did get those gigs. For an emerging artist, not being an artist’s assistant can mean missing out on potential mentors, invaluable introductions, or at least some solid bits of wisdom. On the flip side, there’s the potential for feeling insignificant, less than competent, even disposable. For many assistants, stress, disillusionment and/or bitterness are never far away.

In mid-February, art writer and curator Emily Colucci published an entry on her website, Filthy Dreams, called “I Found It: The Worst Art Job Listing Ever Created.” The listing was posted in the New York Foundation for the Art’s (NYFA) classifieds, reciting an immense litany of tasks to be performed for an ‘Art World Family.’ Colucci described the classified ad as “the most nightmarish job listing I’ve ever seen in an art industry filled with nightmarish jobs.” The job posting was deleted from NYFA’s site the day after she posted.

It turns out the parents of this ‘art world family’ are the artist Tom Sachs and his wife, former Gagosian gallery director Sarah Hoover (who has also been referred to as a ‘fashion influencer;’ she describes herself as “an art historian, writer, and cultural critic”). Since their outing as the family behind this over-the-top-yet-real job post, Sachs’ reputation has taken a big hit. There’s been extensive reporting about the studio he’s been running, including allegations of workers being paid minimum wage, a cult-like workplace, and assistants conducting menial tasks for Hoover as part of their job while supposedly working just for him. Sachs’ relationship with Nike, with whom he developed the “NikeCraft: General Purpose Shoe,” has become strained, and sneaker aficionados and artists alike have called for Nike to cut ties with him (the artist Corey Escoto painted a Nike Swoosh above the words “Just Drop Him” on the side of a truck).

Art reporter Sarah Cascone, who thoroughly covered the scope of Sachs’ unspooling for Artnet, quoted a former employee who described a culture of sexual harassment, affirmed by other former employees. “He’s very open about his sexual preferences in a woman — things that no one you work with should know about,” said a former employee going by the pseudonym Mary Anne.

The fascinating if often disconcerting leaks coming out of Sachs’ studio breed a sense of schadenfreude for the couple’s, shall we say, unsympathetic behavior. But of all the commentary that’s been written in recent years about separating the artist from the art — whether it’s Woody Allen or JK Rowling, and in the art world Picasso or Chuck Close — this is ultimately more about workers’ rights and the asshole culture within the art world. Sachs was pushing the boundaries of how a highly staffed studio can perform: the atelier as cult. After polling people on social media, I don’t have anything conclusive to offer. Most assistants who work for Big Studios sign NDAs, and those who don’t are still generally very careful about sharing with anyone beyond close friends. Sure, I received indications that X artist was to be avoided, that Y artist cultivated a sexually inappropriate climate, and that Z artist’s studio had an oppressive office environment, one that was admin-based and kept separate from the artist’s production side of the business.

To give you a sense of Z artist’s studio, here’s what a former employee shared anonymously: “The Studio Director — the artist's wife — was the one who I really worked for. Their relationship was highly fraught. She managed the business … and she was a micromanager. For the first year, until she trusted you to answer emails yourself, you had to copy her on every email you sent. Overnight, she would respond to you only if you did something she didn’t like in an email, and would tell you to email the person back with a new answer, copying her on your new response. It would be common to walk into the office in the morning to find a letter length list on your desk of things that you did wrong and needed to fix upon arrival that day. She would sit and eat breakfast behind us, watching us. Oh, and it was a silent office. No music / sounds / anything.”

What they describe is unpleasant on its face. But unlike the artist in this scenario, who is still an artist, working for Sachs became a point of no return for the pseudonymous Mary Anne: “I just can’t believe I wasted years of my life. I still have nightmares about it,” she said. “I really, really wanted this job, and I was so happy that I got it — but I don’t think I will work in the arts again.”

What are the most relevant takeaways from all this? Is the culture of big artists’ studios good for the artists who operate them? Is it good for the art world as a whole?

Sure, studios employ multiple artists, providing them steady work and, sometimes, good pay, connections and/or health insurance. However, the more artists there are employed in studios, the more the pyramidal structure of the art world perpetuates. That’s just basic math. Is it possible both to have numerous artist studios employing, for better or worse, substantial teams of artists, providing jobs for assistants who help their employers to realize their most ambitious projects — and maintaining an art community that is equitable to artists and artist workers alike? I don’t see how that can work.

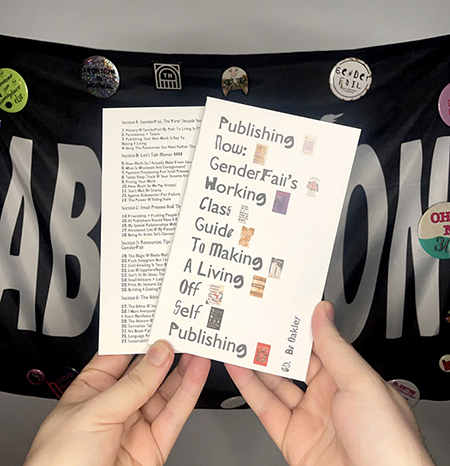

Through Instagram, I recently discovered the publishing platform GenderFail, run by Be Oakley. In their publication “Publishing Now: A Working Class Guide to Making a Living Off Self Publishing,” the book concludes with the section “I Want Everyone in the Art World to Be Middle Class: A Short Manifesto Against Rich and Powerful Artists.”

Most of us want an equitable art world. But in an art world chock full of elite artists running poly-staffed teams making up the top of the pyramid, things will not change for the artists in the middle, let alone at the wider base. In an Instagram post about “A Working Class Guide,” GenderFail wrote: “Our day to day lives are affected by capitalism, by having little or lots of money. To needing money for living expenses. In these limited terms I fall into the middle class category, and since this system exists, I’d rather we all be middle class, in terms of having a living wage, having enough money to make our work and having resources for the future, than this system of unequal access to money.”

Sounds reasonable to me. On the road to greater equity there will need to be far fewer Big Artists Studios like Sachs’. At the present time it’s a system that favors the hoarding of capital, coopting the brain power and the emotional resources that for the rest of us are so often in short supply. But overturning a culture enabling the centralization of artists’ studios is akin to overturning predatory capitalism: it’s a big, seemingly intractable ask. You have to start somewhere, though, and dreaming of such a change is a good place to start.