“Together in Time: Selections from the Hammer Contemporary Collection”

UCLA Hammer Museum, Los Angeles, California

Continuing through August 20, 2023

“Afro-Atlantic Histories”

Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA), Los Angeles, California

Continuing through September 10, 2023

When I read Christopher Knight’s words, “The Hammer is the Woke Museum,” in the March 27 L.A. Times, I felt compelled to visit the exhibition under review, “Together in Time.” Soon after, I read Bill Lasarow’s Substack essay “The Opportunity of Woke,” in which he explained American liberalism’s moral virtues (along with the term’s history) and their vital importance in today’s world.

Walking into the Hammer was to enter a world of comrades, or lantzmen, as my Jewish forebears would call them. There were visitors of varying backgrounds, colors, and sexual proclivities reveling in the treasures on display. Many pieces extoll the inclusion and cultural diversity of the world we wish to live in. These features were prevalent in the current lead exhibition, “Together in Time: Selections from the Hammer Contemporary Collection.”

The 73 artworks, in an array of media, are described as “the largest presentation of the Hammer Contemporary Collection in the museum’s history.” Included are works by superstars such as John Baldessari, Chris Burden, Mark Bradford, Bruce Conner, Noah Purifoy, Patssi Valdez, along with many others. The individual pieces and their well-curated juxtapositions provide a vision of tolerance and diversity, functioning as a welcome antidote to the right-wing tirades pervading the airwaves.

Highlights include Sasha Gordon’s oil “Bonfire” (2021), displaying several young women, simultaneously joyous and irate, as they dance around a bonfire, scantily clothed or unclothed. This piece conveys a sublime sense of freedom through the casting off of society’s pseudo norms. Nigerian Njideka Akunyili Crosby’s mixed media “Ike Ya” (2016) is a finely wrought figurative work, overlaid with collage and complex patterns. The image depicts a couple in a deep, soulful embrace. The painting’s empathetic nature and racial inclusiveness epitomize this exhibition. By contrast Bruce Conner’s “Crossroads” (1976), a video compiled from 1950’s films of nuclear test explosions in the Pacific, presents humankind’s urge to create ever more massive and terrifying explosives. The film is a metaphor for the cultural and societal invectives we are forced to live with.

The great German polymath Johann Wolfgang von Goethe wrote, “Art reveals the hidden laws of the world, which without art would remain hidden.” The dictum aptly elucidates the decidedly ‘woke’ art comprising “Together in Time.”

Inspired by the Hammer a visit to the “Afro-Atlantic Histories,” a widely traveled exhibition currently at LACMA, also revealed itself to be a woke show. It depicts, through art old and new, the transatlantic slave trade and legacies of the African diaspora, which included Latin America, the Caribbean, the United States, and Europe. With over 100 objects spanning the 17th to 21st centuries, it reveals the travesty and pathos that slaves and their descendants endured. The term “histories” here conveys a more expansive account of those draconian actions than most of us are familiar with.

In Nona Faustine’s photo, “From Her Body Sprang Their Greatest Wealth” (2013), the artist had herself photographed almost entirely nude, standing at a busy Wall Street intersection. Various New York City locales, including Wall Street, had been sites for slave sales, as one of our earliest forms of wealth was the ownership of black bodies. Displaying her own nude body, the artist projects the vulnerability of black women of the past, translating it into contemporary defiance.

Aaron Douglas’ painting “Into Bondage” (1936), with its Cubist and Art Deco elements and tropical foliage, shows enslaved Africans with their hands shackled, walking with resignation toward waiting slave ships. Yet one tall figure gazes hopefully toward a beam of light, referencing the North Star.

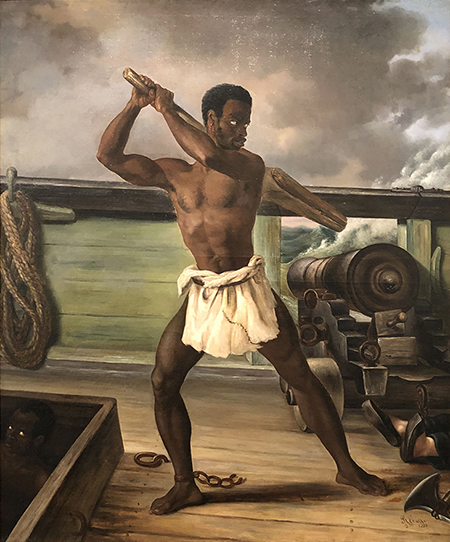

The “Enslavement and Emancipation” section of the exhibition depicts agony, despair, and defiance. Edouard-Antoine Renard’s “A Slave Rebellion on a Slave Ship” (1833) features a black man wearing a loincloth, clutching a large wooden club, attacking a white man whose ankles and shoes are shown. Paul Cézanne’s “Scipio” (1866-68) shows an exhausted slave with his head resting on his arm. And Faustine’s “Isabelle” (2016) places her in front of a plantation home, nude from the waist up, wearing a long white apron, grasping a large frying pan. The suggestion is that she is valued for domestic skills as well as for her body.

Faith Ringgold’s painted quilt, “Subway Graffiti #2 (1987), includes numerous people, black and white, huddled together on a subway platform. We know it is only a momentary gathering that will disperse as they reach their stops. Alison Saar, who frequently references the African diaspora and black female identity in her work, contributes the 20-foot-tall sculpture “Fanning the Fire” (1989). It depicts a black maid wearing a short skirt, fanning a fire, probably for a rich couple’s home. The piece implies that wealthy white people still propagate the myth that black people should serve them, not lead lives of purpose and dignity. By contrast, Ernest Crichlow’s “Harriet Tubman” (1953) reveals the fierce determination of the abolitionist and social activist, clothing her in a dignified green cloak.

Finally, there is the strong dose of defiance in Jamaican artist Osmond Watson’s “Johnny Cool” (1967). An intense black teenager stares out at the viewer, seeming to say under his breath, “DON'T FUCK WITH ME.”