Continuing through July 22, 2023

An accomplished practitioner of hand stitched as well as digitally controlled embroidery, New Yorker Elaine Reichek has succeeded, over the course of five decades, in breaking down distinctions between the so-called fine arts and everyday crafts. In Reichek’s view, the two genres are not so dissimilar, a point that she makes in her current exhibition. Here she juxtaposes two traditional hand-embroidered darning samplers (one devoted to the alphabet and numbers, the other to decorative patterns) with one that replicates in thread a composition based on a 1970s color grid by conceptual artist Sol LeWitt.

Reichek often reimagines the work of male artists, only using thread, a medium and discipline historically associated with female domesticity. As a medium it has served as a means of questioning the absence of women, until recently, throughout art historical canons. Nevertheless, it is fitting that Reichek pay homage to LeWitt, one of the chief architects of conceptual art. In her own work she adheres to his belief in the primacy of ideas. She diverges from LeWitt’s approach in that her art is not determined by specific procedural rules, which allows her more creative freedom and a wider range of expressive possibilities. Whereas LeWitt’s work is usually minimal in form and serious in tone, Reichek’s covers a wider spectrum of styles and temperaments, ranging from abstract to representational and from sensuous to playful.

Among the wittier works here are two large-scale works that brilliantly parody the drip paintings of Jackson Pollock. In lieu of conventional canvas, Reichek has embroidered “JP Textile/Text 1” and “2” using cotton fabric that was manufactured by Kravet, Inc. and printed in a Pollock-like pattern known as “Spatter.” Over these found compositions, Reichek has digitally stitched multiple bibliographical references to writings on Pollock, camouflaging them within the preexisting allover matrix. In one version, the altered fabric is mounted over wood and hung like an actual Pollock painting. In the other, it extends across the wall laterally, pulled from a metal dispenser that contains the unused portion of the fabric roll, mimicking at once a wrapping-paper table and a religious scroll. While the bibliographic entries sewn into these works call attention to Pollock’s well established position within art history, the mass-produced fabric reminds us of his great commercial success and influence on popular culture. To reinforce this line of thinking, Reichek also exhibits a triptych of silk charmeuse scarves on which she has printed photographic images taken by Cecil Beaton in 1951 for Vogue Magazine, that show fashion models posing in front of Pollock paintings.

Pollock is not the only male modernist superstar to come under Reichek’s scrutiny. An entire gallery is devoted to a complex installation that serves as a mini-art history lesson and dialogue about Henri Matisse. In the center of the gallery, the folding screen “Screen Time with Matisse” (2022) is covered on both sides, from top to bottom, with a variety of patterned fabrics and swatches, photographs of fashion models, postcards of Matisse’s paintings, and even a color chart. Behind this (and not fully visible upon entering the space) is a staged visualization of a section of Matisse’s studio, complete with a decorative carpet, vintage Victorian parlor chairs, a table, plant stand, flowers, fruits, and fabrics.

Elsewhere in the installation we are informed about Matisse’s relationship with the Bloomsbury Group, an early 20th century British circle of artists and intellectuals who were influenced by him but preceded him in designing actual clothing. Bloomsbury painter Duncan Grant’s “Still Life with Matisse,” which shows a vase of flowers atop a checkered tablecloth in front of Matisse’s well-known painting “Blue Nude,” is exquisitely replicated by Reichek in a hand-sewn embroidery where the contrast between exposed raw canvas and colorful, textured stitching yields a particularly lush and vibrant effect. To illustrate clothing designed by Grant and fellow Bloomsbury artist Vanessa Bell, Reichek includes two period-style dresses made from fabrics featuring their designs and displayed on vintage wooden clothing stands. Employing the museological strategy of educating with labels, Reichek has pinned the dresses with embroidered clothing tags featuring quoted remembrances of Bell by her daughter and granddaughter.

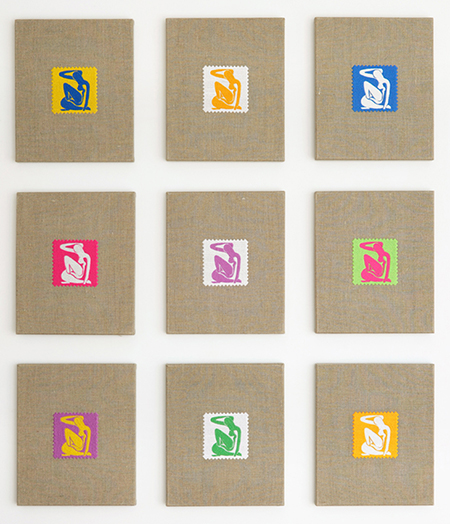

Reichek’s appropriations of Matisse’s compositions range from the large scale “Scattered Sheaf with Felt and Fabric” (2022), which reimagines a ceramic wall relief in the medium of felt, to two small, intimate samplers (2006-07), where Matisse’s imagery (including “Blue Nude”) appears in a variety of colors in the form of embroidered swatches that resemble postage stamps with their zigzag edges. Reichek wisely chose to use digital stitching for the latter, as the process yields a tighter interweaving of the threads and a flatter surface. This seems better suited than a more textured approach to the joyful expression of pure unmodeled color. By contrast, working by hand is equally effective in capturing the sensuousness of curving lines and handwriting in three works where Reichek uses black thread to embroider Matisse’s sketches and inscribed notes for different tapestries.

A Matisse composition is also present in Reichek’s, show-stopping installation of 24 small embroideries, both hand- and digitally sewn, that extend the concept of a sampler to an entire wall. In most of these cloth tiles Reichek embroiders a detail of clothing or other types of fabric that she appropriates from art historical sources, cleverly converting a painted image of a textile back into its original medium. Arranged in three horizontal rows, the installation presents a fascinating inventory of artists, including Old Masters Michelangelo, Bronzino, and Chardin, 19th/20th century painters Delacroix, Vuillard, Picasso, and Miro, and present day figures Kerry James Marshall and John Currin. Although male artists dominate, there is a notable presence of women in the mix, among them Artemisia Gentileschi, Sonia Delaunay, Alexandra Stepanova, and Meret Oppenheim. In addition to enlightening us about different approaches and styles that have been used for centuries to render textiles, the installation contains several aesthetically distinguished gems. Overall, the sampler installation is a great testament to Reichek’s art-historical chops, as well as to her sheer virtuosity as an artist.