Continuing through September 18, 2023

Until the right term for a conjunction between the terrifying and the comic comes along, “tragicomedy” will have to suffice, although it is too vague and too soft for the task at hand. If such a word existed, the more than sixty works included in “Hell: Arts of Asian Underworld” would provide multiple opportunities to use it. “Hell” is an amazing exhibition that ranges across ten centuries and almost as many cultural traditions. Given this breadth the show, astutely curated by Adriana Posner and then revised by Dr. Jeff Durham, challenges and expands upon everything that we thought we knew about Asian art.

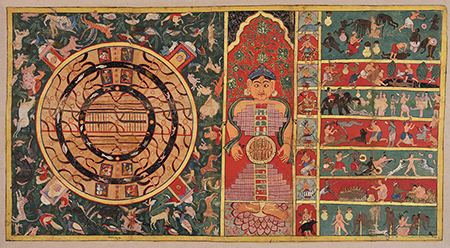

The exhibition includes two stunning paintings that are anonymously authored examples of the Theravada Buddhist Bravachakra, or wheel of life illustrating the idea of Samsara, the cycle of life, death, and rebirth. In them, a centrally positioned mandala is divided into pie-graph slices containing vignettes of everyday misery elevated to incidents of cosmic persecution, some comically absurd, others outright terrifying. Presiding over this rinse-dry-repeat cycle of striving and suffering is Mara, a three-eyed Buddhist deity personifying the inextricable forces of time, death, and illusion-delusion. He is portrayed as a fanged glutton who takes schadenfreude delight in the torments meted out by unenlightened fate, knowing that the silly humans populating his domain will never learn the lessons pertaining to their self-inflicted misery.

Other works from India tell us that Mara has a close Hindu cousin named Yama, who is the king of the underworld and the god of death. In an ink and watercolor work attributed to Gursaha from the early 19th century titled “The Court of Yama, the God of Death,” hell is portrayed as a Kafkaesque labyrinth where the recently deceased undergo extensive bureaucratic humiliation prior to finding their way to a center-point where the enthroned deity dispenses harsh judgment without mercy. In the anonymously authored “Kingdom of Yama” from a century later, two such labyrinths are depicted in deep space perspective, both saturated in rich nocturnal color. Access to them is made even more challenging because of a series of smaller “purgatory” structures where the soon-to-be-damned are subjected to a parcours of preliminary tortures. In a small, albeit irresistibly charming woodblock print from Japan’s Meiji era (1868-1912), Utagawa Yosifuji depicts three layers of hell wherein sadistic cats reign supreme over hapless mice. The print is an example of Giga, a style that has been said to spoof the earlier and more widely known Ukiyo-e (literally meaning “floating world”) genre. Giga images have also been said to anticipate the Manga comic illustration style that is now familiar to millions.

Many of the works included in the exhibition are singular figures that portray demons related to Hell. “Emma-o, King and Judge of Hell,” a sitting carved wood figure from Japan’s Muromachi period (c. 1400-1500), looks like a dyspeptic judge preparing to pass the sentence of just deserts. His face speaks volumes, conveying sadistic delight in the task to which fate has appointed him. Also included are several Ukiyo-e woodblock prints portraying famous actors in demonic character. One of those characters, played by Ichikawa Danjuro VIII, is the law-breaking bodhisattva Jiso, who tricks Emma-o into letting “truth-tellers” escape damnation. The actors and courtesans of the Edo period had a lot invested in Jiso’s ministrations, because it was he who could rationalize how they floated above the travails of everyday life.

Another among the many stunning works in the exhibition is the large painting titled “Jigoku, The Hell Courtesan” (1850) by Utagawa Kuniyoshi. In it, we see a figure coyly looking back over her shoulder, clothed in an elaborately embroidered garment depicting aspects of her self-degradation and subsequent enlightenment. Peering out from behind the garment, we can detect the face of a precocious young child who Jigoku tries to protect from the viewer’s gaze. By contrast, portrayals of Datsueba, the withered Hag of Hell show up throughout the exhibition. The best of these is an Edo-period painting on silk by Kikuchi Yosai titled “Datsueba, the Old Woman Who Snatches Away Clothes” (1845). Here, we see the grotesque old crone perched like a decrepit gargoyle in a tree branch, waiting to inflict misfortune and misery on a passing trio of hapless children.

A rare instance of transcendent hope is also present in the exhibition, represented by the “White-Robbed Water-Moon Avalokiteshvara (Gwaneum Bosal)” by Seol Min (2008). Gwaneum is the Korean name for the Chinese Guanyin and the Japanese Kannon (also related to the Japanese and Korean Amita), portrayed here as coming out of the darkness on a golden cloud of divine benevolence, flashing the reassuring smile of compassion and crowned with the halo of divine illumination. In her hand is a vial containing the nectar of immortality.

The exhibition is rounded out by several other recent works from the past 60 years demonstrating the durable persistence of Hell-themed artistic practices, some of which reach back to pre-Buddhist sources. Indonesian artist Wayan Ketig presents a massive scene titled “Bima Swarga” (c.1970) from the Indian epic poem, the Mahabharata. It shows a paradisical landscape teeming with demonic figures depicted in a state of unrestrained frolic. Some of these are perched in tree branches laden with lotus flowers while most of the others congregate in groups to lecherously molest innocent-looking young girls. A 2006 painting by Manila-based Luis Lorenzana titled “Akaldama” depicts Filipino nationalist writer José Rizal reincarnated and descending from the cloudy heavens to condemn the rampant corruption of the Philippine government. In the background we see the Malacañang palace in flames, while its faithless politicians are cast into a chaotic realm of sharp-toothed demons with protruding eyeballs. The Bima Swarga and Akaldama are both world class fever-dreams that make most examples of contemporary Pop Surrealism look like small potatoes served with a side order of weak tea. In other words, they are overwhelmingly zany and nightmarishly disturbing at the same time.

Another recent painting, by Nepalese artist Tsherin Sherpa, sums up the entire exhibition. Titled “The Melt” (2017), it is the only work in the exhibition that might qualify as abstract, even though it symbolizes how the Tibetan deity Mahakala (“Great Time” in Sanskrit) facilitates its own dissolution of all things anchored to its illusion-giving power. The painting accomplished this by taking a Bravachakra mandala and radically distorting its narrative and geometry to make it seem like it is melting into an eternal non-existence at long last set free from the wheel of karma. This melting effect is all the more convincing because it is set against a vibrant field of glistening gold. That’s right, real gold, not the down-market imitation gold that always looks like the stuff of costume jewelry.