Continuing through October 21, 2023

Even though this is Chris Johanson’s fifth exhibition at Altman-Siegel, it feels like the first. That is because the three related works included in it are from 2000, having recently been rescued from storage in advance of the artist’s decampment to Los Angeles a few months ago. Prior to that move, Johanson had been dividing his time between Portland, Los Angeles and San Francisco, gaining a great deal of art world attention as a key member of what has been controversially dubbed “The Mission School.” This was a group of San Francisco artists working in a hybrid style that absorbed and repurposed the influences of street art, Funk assemblage and Japanese underground comic illustration. Adamant about reflecting personal circumstances, their work came as a breath of fresh air that contrasted favorably with the peak mania for Biennial globalism that was already running out of gas in the late 1990s.

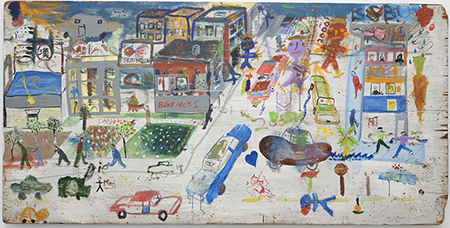

Johanson’s trio of paintings, designated “Untitled Triptych,” offers a rare, time-capsule glimpse into the formative stage of the The Mission School aesthetic.

There is no central panel with flanking sub-narratives, so maybe aesthetic is not the right word. I say this because Johanson’s “Triptych” is better understood as an anthropological relic that both captures and codifies the spirit of its time and place. That time and place was San Francisco’s once-affordable Mission district, just prior to its capitulation to the forces of gentrification. It reminds us of Fred Armisen’s famous quip (from 2011) about Portland being what the whole country would look like if the Supreme Court had ruled Al Gore the winner of the 2000 election.

Such observation would also be applicable to the Mission district of the 1990s, which Johanson’s “Triptych” re-imagines as an idealized sociological tidepool of convivial diversity, underfuned for sure, but maybe the last true bohemia in the nascent age of telematic identities.

Johanson’s “Triptych” also bespeaks a final moment of trust and community innocence that was irreparably ruptured when the 9/11 terrorist attacks ushered in a newly pervasive National Security State. It is worth remembering that change took place little more than two decades ago, although it seems a much longer time than that.

Each of the three panels are repurposed 4 by 8 foot sheets of distressed plywood primed with white house paint. Inscribed upon these are perspectival views of streets viewed from a third story vantage, radiating outward toward an ambiguous horizon. Each street is teeming with signs of life, including cartoonishly rendered figures and dilapidated signage advertising down market goods and services. These features are rendered in house paint with just a bit of acrylic. Tightly outlined forms are juggled to set against other more painterly areas. These are earmarked by flowing and occasionally dissolving color. The coordinated balance between these casual materials and a lowbrow depiction of casual lifestyle is made clear in all three panels. The point made by the work is that art needs to be an integral part of a community of interest.

The story of how Johanson’s “Triptych” came into being is itself an interesting one. As part of a larger exhibition at the DeYoung Museum, he hosted a workshop where he invited members of his Mission District community to come and collaborate on the three panels. Needless to say, those community members were not part of the normal museum-going demographic, but their collaborative contributions proved to be one of the exhibition’s highlights.

The result was that the panels took on the look and purposes of the old Surrealist “exquisite corpse” projects, only with more collaborators, and an imaginary neighborhood community standing in for singular figures favored by the Surrealists. Johanson’s “Triptych” also brings another important question into the foreground, one that was particularly relevant in that immediate aftermath of the collapse of the National Endowment for the Arts*: “Who gets to be an artist?”

“Triptych” points accusatorily to the exclusionary class structure of the officialized artworld that had by then arisen. The cause was in part in response to the multiple political attacks that had been leveled against it. It is a question that is relevant now, even as many recent answers fail to take another question into account: “what constitutes a successful and effective work of art?”

* The 2023 budget for the NEA is almost $230M; over the last decade or so it has become more robust. —Ed.