Continuing through November 25, 2023

Six figurative oil paintings by Jeffrey Chong Wang show a distinct command of the medium matched with a wide-ranging and imaginative vision. A cast of Chinese figures populate settings that verge on the theatrical. These paintings read as set pieces that present an awkward sense of space and situations informed by Western painting, whose history they also critique.

Wang intentionally distorts anatomy and spatial relations to evoke an ominous discomfort and anxiety bordering on distress. This is evident because Wong’s dramatis personae are depicted as withdrawn into themselves. They confound our perception and understanding of the overall images, which adds both mystery and delight to their viewing. Each rigorously detailed face is drawn from family portraits, which suggests the artist’s deep connection to his ancestry.

Wang’s paintings are “uncanny” in the way that Sigmund Freud described over a century ago, denoted for art that is both familiar and foreign, weird, or bizarre. “Uncanny” has often been used to describe Magic Realist painting, a branch of Surrealism that Wang puts to good use in this body of work. Comparisons to Giorgio de Chirico, Paul Delvaux, and Balthus are evident and instructive when considering Wang’s work. But he also draws on a wider historical perspective.

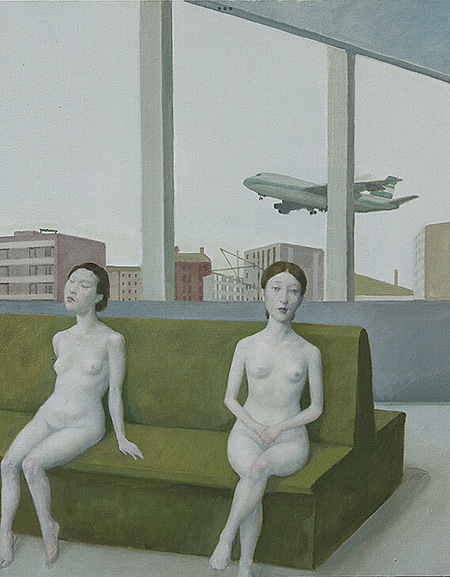

In “Two Models Resting” two nude female figures occupy a green bench situated in a public setting. They dominate the lower half of the canvas, while the upper half reveals a window through which we see a plane flying over a row of buildings, suggesting they are in an airport lobby. The women have large heads, narrow shoulders, small breasts, and hands and feet that distort anatomical accuracy. One stares out of the picture frame while the other looks out but avoids the gaze of the viewer. These two beauties reference the style of the German 16th-century master Lucas Cranach the Elder, best known for his religious paintings, presented here in a contemporary scene unrelated to religion.

In four of Wang’s paintings, he places a man and a woman in some sort of uncomfortable and surreal scenario. For instance, in the mesmerizing, almost scary “Donkey in the Gallery,” a beautiful woman with a forlorn expression occupies the foreground to the left. It looks like she’s being pursued by a well-dressed man outfitted in a suit, tie, and hat — kind of a dandy — who peers toward her from the right side of the canvas. He is strangely small in scale, making his presence feel ominous. The head and neck of the titular donkey appears in the background between the two protagonists, thus separating them.

In Surrealist painting and the films of Luis Bunuel, animals were often placed within a tableau to underscore the abnormality of the scene, a device often referred to as the “marvelous.” Wang seeks the marvelous in several paintings. On the back wall of the gallery is an image of a Christ-like figure that bleeds from wounds to his forehead and side. His arms are raised in a peculiar way across his chest. The left seems to be missing its hand. A woman mimics his gesture, but her hands are intact. Her eyes turn upwards as in Old Master paintings of saints and martyrs whose expressions appeal towards heaven. Here, however, the presence of bright red lipstick, in the context of the rest of the composition, suggests a longing more sexually than spiritually ecstatic.

In “Shy Poet” another dandy wearing a long dark sport coat and tie, his hair distinctly parted, occupies the foreground at the right side of the composition. He stares out dreamily without meeting our gaze, right hand concealed in his pocket. His back is turned to a young lady sitting on a couch, legs crossed, wearing a bland yellow dress, with her eyes closed. A window at the back of the room offers a view of a building and trees, while a cropped mirror exits the frame to the right as it reflects an otherwise unseen figure in a blue coat, hinting that there are two different men. Which of these figures might be the poet? Or perhaps the painting registers a dream of the poet, or the artist, who remains offstage. Or any of the three figures could be the poet, imagining the others in an otherwise banal and empty room dripping with an ambiance of mystery.

The artist has discussed how his paintings navigate the “imbalance” between his internal mental life and the outside world. The dualistic choice of this term is influenced by Descartes’s famous response to the question “what am I?” First there is “I think,” or “res cogitans,” and then there is “therefore I am,” “res extensa.” In his painterly attempt to reconcile these two realms, Wang bears witness to an immeasurable conundrum that remains unresolved after centuries of philosophical and aesthetic inquiry.