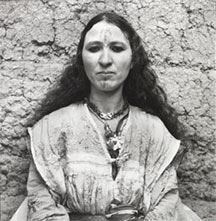

Marc Garanger, 'Algerian Woman,' 1960, gelatin silver print.

At the end of August 2003, four months after then-President Bush had made his infamous Mission Accomplished declaration aboard the aircraft carrier USS Abraham Lincoln, the less delusional Pentagon screened Gillo Pontecorvo’s 1965 classic “Battle of Algiers,” thus tacitly signaling that, if anything, the mission in Iraq was just beginning. “Battle of Algiers” chronicles the launching and eventual destruction of an Arab insurgency aimed at gaining Algerian independence from France. Having lost Vietnam in 1954 and granted independence to Morocco and Tunisia in 1956, the French were determined to hold on to Algeria at all costs. Using summary detention, systematic torture and assassination, the French crushed the urban insurgency in the capital, Algiers, but in the process galvanized the Algerian population against French rule. Prefiguring what Americans would learn the hard way in Vietnam, the French won every battle of the Algerian conflict for independence but lost the war. By 1962, France had had enough and Algeria gained its independence. The French army withdrew and on its heels, more than a million Algerian French colonists (dubbed pieds-noirs) fled to France.

The idea that the U.S. could learn from “the challenges faced by the French” (as one Pentagon official was quoted saying at the time of the “ Battle of Algiers” screening) was perhaps more revealing than intended. The challenges for the French in Algeria were the challenges of a colonial European power bent on subjugating North Africa. The conquest of Algeria started in 1830, was met by fierce resistance, and took all of 70 years to be completed, after one-third of the Algerian population had been wiped out. France then imported thousands of settlers (many of them from Spain, Italy, and Malta) into the newly conquered territory. These settlers received French citizenship and the right to vote and send representatives to France.

By the time the Front de la Liberation Nationale (FLN) launched its terrorist campaign against French occupation in 1954, French citizens comprised a tenth of the Algerian population and Algeria was administered as if it was not merely a colony but an integral part of France. It was this particular fiction of a French Algeria, that is to say the fiction of Algeria as not merely a conquered territory but an assimilated one, that gave the struggle for independence its terrible existential ferocity. As Franz Fanon wrote at the time, “I owe it to myself to affirm that the Arab, permanently an alien in his own country, lives in a state of absolute depersonalization.” Fanon joined the FLN after, as head of an Algerian psychiatric hospital, he became aware of the mental toll torture exacted on both its victims and those who administered it. For him the uprising against the French was not simply a matter of national liberation but, just as urgently, a struggle to eject from the colonized psyche the self-hatred that 130 years of racial subjugation had engendered in it.

What is telling about the notion that “we” can learn from the “challenges” the French faced in Algeria is the admission implied by that notion that the American military’s mission in the “war on terror” is essentially a colonial one. Back in 2003, nobody in the mainstream media wanted to pick up on that. No one at that point went beyond arguing about the proper tactics to use against the enemy to start questioning the axioms of the war itself. Perhaps we are beginning to see a shift? The Getty Research Institute’s mounting of “Walls of Algiers: Narratives of the City” might then be a sign of a dawning acknowledgment that an answer to that clumsily loaded question, “Why do they hate us?” may actually require some consideration of history before 9/11. And an appreciation of who the “they” are that attempts to move beyond the reduction of the Muslims to pure demonic “others” with whom no negotiation is possible.

One of the things that I think the Getty show does well is to consistently remind the viewer that the very existence of the images in the exhibition reflects the often unseen presence of the occupying power. In some cases, the subject itself (for example, an equestrian monument of the Duc D’Orleans in front of an Ottoman building) discloses this occupation readily enough. In other instances, as in the case of “Negresse Marchande du Pain” (which the curators decorously translated as “Bread Seller”) the colonial gaze constructs an exotic object. One of the most confrontational images in the show is that of a woman with tattoos on chin and forehead, back against a wall, and gazing back directly at the photographer. The subject could easily pass as innocuous, until we read the caption. It is photographer Marc Garanger’s, explanation of how he took the photograph:

“In 1960, I was doing my military service in Algeria. The French army had decided that the indigenous peoples were to have a French identity card. I was asked to photograph all the people in the surrounding villages. I took photographs of nearly two thousand persons, the majority of whom were women, at a rate of about two hundred a day. The faces of the women moved me greatly. They had no choice. They were required to unveil themselves and let themselves be photographed. They had to sit on a stool, outdoors, before a white wall. I was struck by their pointblank stares, first witness to their mute, violent protest.”

While, inevitably, some of the photographs in this show tend to stand out, the exhibit’s overall design aims to weave images and texts from a multitude of sources (including postcards, lithographs, news photos and texts excerpted from novels, poems, scholarly journals, and government reports) into a complex picture of the changes wrought by the French presence on the physical structure of the city and the lives of its inhabitants. As the curators note, “From the French conquest in 1830 to its independence in 1962, Algiers served as an experimental site where intricate colonial strategies were rehearsed and tested.” Ultimately, those intricate colonial strategies came to nothing. Since then, colonialism has become the policy that dare not speak its name. That’s progress of a sort.

Published courtesy of ArtScene