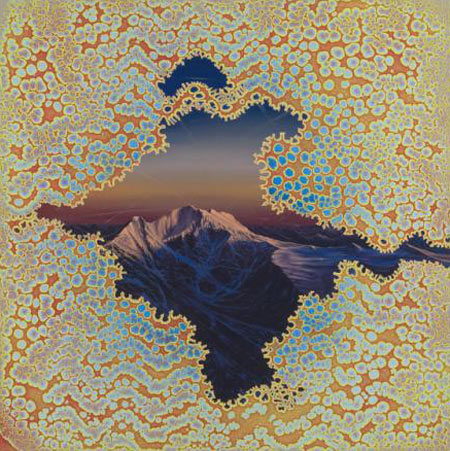

“Micro Chasm” is a particularly succinct title for Shane McAdams’ current exhibition, as the works integrate microscopic forms with macrocosmic landscapes: chasms, canyons, waterfalls, and mountainscapes, many of them inspired by the Brooklyn-based artist’s childhood in the southwest American desert. With conceptual invention and technical virtuosity, he combines semi-abstracted imagery that evokes the biological sciences with old-school landscape painting of the Hudson Valley School lineage. In years past, McAdams drew and painted abstractly, incorporating diverse media such as Elmer’s glue, resins, pigments, even ballpoint pens, in exultant compositions that exploited surface and materiality as ends in themselves. More recently, his long-standing fascination with geologic topographies compelled him to marry his material explorations with finely brushed paintings in a series he calls “Synthetic Landscape.”

As framing devices he uses clustered forms resembling cells, amoebae, and chloroplasts, configured in organic compositions shot through with holes of varying sizes, which function as windows through which the viewer peers. On the other side of those windows are dramatic vistas painted with realist, if not quite hyperrealist, precision. In “Synthetic Landscape (Iceberg),” he finesses the transition between abstract foreground and naturalistic background by rendering the crackled ice water surface in a spiky, straight-edged fashion that is more the province of perfect Euclidean geometry than messy organics. This tension, combined with the unnatural linearity of the clouds above the iceberg, effectively questions the point at which microcosm ends and macrocosm commences. Likewise, in “Synthetic Landscape 28(Electricity)” the branching tendrils of a lightning bolt visually echo the lichen-like sprawl of the cutout foreground. This duet continues in images of skyscape “Synthetic Landscape 25 (Vanishing Point),” mountainscape “Synthetic Landscape 23 (Curve of the Earth),” caverns “Synthetic Landscape 24 (Cave Painting),” moonscape “Synthetic Landscape 22 (Sturm and Durango),” farmland “Synthetic Landscape 21 (Parceled Kansas),” and waterfall “Synthetic Landscape 16 (Niagara).”

In a striking sub-series, McAdams frames his landscapes with a different device. Instead of the honeycombed peekaboo windows, he uses vertical lines that resemble aurora borealis, creating a horizontal vantage point for his landscapes. Often these vertical lines are heightened by the use of vividly saturated colors, as in “Synthetic Landscape 27 (Magenta Symmetry)” and “Synthetic Landscape 26 (Cyan Symmetry).” Across this body of work is a playfulness in execution, a musical sense of theme and variations. McAdams delights in making things visible that we cannot normally see, and counterposing them with wide-angle views that tourists ooh and ah over in National Parks. This witty conceit complements a serious undertone endemic to our age of green thinking: the ways in which particles invisible to the naked eye, such as hydrofluorocarbons, are inexorably tied to things that are visible and measurable, such as glaciers and ice shelves. The relationship between molecular and human-scaled concerns, the artist seems to imply, have never been more consequential. That these paintings manage to encapsulate so much while still invigorating the eye is a testament to a vision that updates a classic painting motif with contemporary visual pastiche, and pivots to address ripped-from-the-headlines scientific and political relevance.