Conceptual art can lean so terribly far into our own cranial turf that there’s little on the “outside” for our imaginations to work upon. Consequently, the work of Vernon Fisher is the surprise in the Cracker Jack box; it’s visually splendid. In fact, it offers an absolute embarrassment of riches for our active imaginations to plunder. His show, “K-Mart Conceptualism,” shows us a series of works displaying dexterous montages of television, cold war and pop iconography that, taken together, make for both an interesting visual experience and a frisky, cerebral thrill.

Fisher uses text in a highly effective manner to — pardon the pun — punctuate his art. And, unlike many artists who simply decide it might be hip to incorporate it into their work, Fisher owns it. He utilizes narrative with a sense of humor and a swagger that makes it engaging. Everything from radio dial-in chit chat to an onanistic exploration of (apparently) a widely held infatuation for the young Annette Funicello on the Mickey Mouse Show becomes fodder for reeling us in and capturing us as surely as a bracelet circles a wrist. It’s mischievous in a boyish way, but it also shoves us squarely into the American mindset from which many of us sprang — and that, of course, is emotionally compelling. It’s the solipsistic wave of recognition in which we all feel most at home. It’s snug as moon pies and Kool-Aid — but with a decidedly quirky edge.

“Stick-Chart Navigator” is a triptych displaying a floating diving board as its centerpiece. As a kind of contemporary altarpiece, it works nicely. We’re made to contemplate cleaving the surface of water and plunging its depths. But it becomes far more complex. Layered on top of that central image is text relating a narrative involving a love affair gone awry. We’re regaled with the story of an attempt to understand a perceived dalliance by gathering information about converging radio signals and re-programmed radio buttons. Thus, navigational clues are given that situate us in a narrative in which we, too, participate. The radio becomes a buoy to which we all (narrator included) can cling to gather information about love and its vertiginous rise and fall.

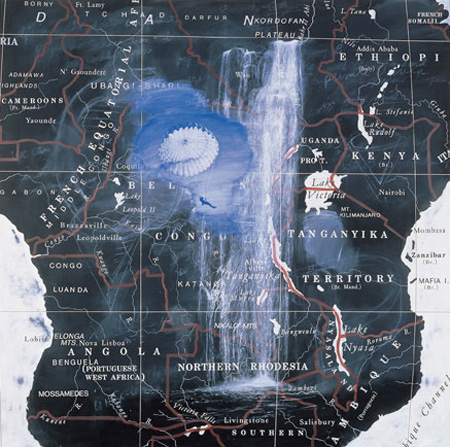

“Bikini” shows us a nuclear explosion blasting up from an otherwise idyllic beach. The water is tranquil and the palm trees are wafting in a delicate breeze. However, those of us who saw “duck and cover” films in preparation for the stand off at The Bay of Pigs will see an eerie resemblance of Fisher’s beach to those we were shown in footage of nuclear holocausts. It was an era of bomb shelters and survival packs. Couched inside the black-and-white image is a colorful bit of effulgent splendor bleeding through in a bright red. We see palms again and looping arcs. But look more closely and you’ll see two trotters plunging downward. All really isn’t well; even the contrasting, colorful, world is tainted with tragic and abysmal intimations.

But, what are we to expect? After all, this is some terrific art. It’s no sunny paradise. Fisher doesn’t just give us a slice; he’s baked a whole pie. You know? The kind you’d recognize from fifties’ commercials. K-Mart, indeed!