In the twelve wood-relief paintings and seven oil paintings that comprise “Oregon Landmarks: Recent Work,” Tom Cramer offers a romanticized vision of his home state while deftly critiquing the boundaries that separate high art from kitsch. The painter is best known for his work in two related styles: a naïve figuration informed by Keith Haring and Afro-Caribbean folk art, and a more refined semi-abstraction inspired by his travels to India and the Middle East. In the former mode, Cramer is at his most colorful and absurdist, in the latter he uses gold, silver, and copper leaf to evoke the gravitas and spirituality of Indian mandalas and the golden Buddhas that dot Southeast Asia. Both styles rely on fragmented chunks of color that fit together, puzzle-like, in mosaics of intuitive form.

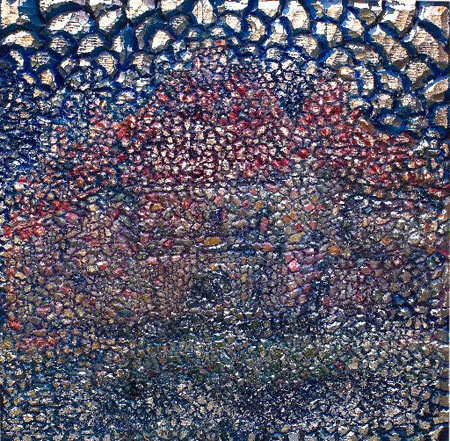

In the artist’s latest body of work he integrates aspects of both techniques, meeting them halfway in his semi-abstract depictions of Oregon’s natural wonders and manmade landmarks. Essentially pointillist in nature, the works read as Impressionist dots, dashes and islands of color when viewed close up. From a pace or two back they coalesce into images instantly recognizable to most Oregonians, as in “Mount Hood from Lost Lake and Pittock Mansion.” Cramer achieves his illusionism by varying the color palette and the density of relief carving to distinguish foreground from background. The large, diffused segments and silvery-blue hues in the upper third of “State Capitol Building” delineate the sky from the building’s tightly carved and gray contours. Elsewhere, as in “Crater Lake Lodge” and “Multnomah Falls Lodge,” distinctions are less clear, the structures camouflaged by the sylvan lushness of their settings. Other times the artist zooms in for near-abstract floral close ups (“Darlingtonia State Park near Florence, Oregon”) or allows the emotional tenor of a place to supercede strict representation (“Oneonta Gorge”).

Given the trippy optical effects and tourist-attraction subject matter, the viewer is free to speculate about Cramer’s intent. Is he offering up slide show visions of a Northwest utopia, or is he wryly critiquing regionalist pride and roadside-attraction kitsch? Indeed, the works appear to be in on the punch line, even as they revel in the setup. They wear romanticism on their shirtsleeves, even as their rough-hewn contours, over-the-top gilding, and often brash colors erode that very romanticism with winks and nudges. Perhaps “post-ironic” is the most apt characterization, given Cramer’s have-your-cake-and-eat-it-too remarks when interviewed a week before his opening: “Whenever I go to a place like Oneonta Gorge or Timberline,” he observed, “I think about the way Alan Watts and Gary Snyder wrote about nature. It was a romantic, Thoreau-like attitude. I’m definitely in that camp, but I also like Hanna Barbera cartoons, miniature golf courses, and cuckoo clocks. I don’t necessarily think ‘kitsch’ is a four-letter word.”

Whatever the viewer’s reference points, the works are uniformly confident, lively, and well-executed. Their retinal and conceptual ambiguity portray iconic Northwest scenes in a fashion more interpretive than documentarian — think Werner Herzog, not Ken Burns. Aiming for esprit over gestalt, Cramer has conjured a quirkily singular sense of place.