Continuing through August 21, 2011

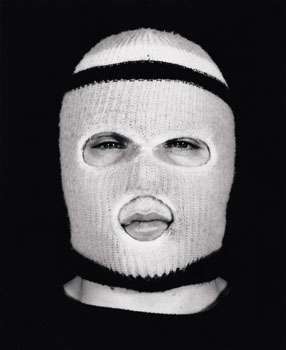

The idea of performance and surveillance has, in recent years, become conflated. Between the blur and overlap of personal and professional identities via social media, and the increasing prevalence of video cameras at banks, traffic lights, and convenience stores, the private has gone public. From banking via ATM to sharing the details of (or conducting) one’s private life on Facebook or Twitter, any mundane personal event has gained the potential to be viewed as a performance, given that any individual case has the potential to go viral, whether desired or unintentional.

Andy Warhol, who famously remarked, “In the future, everyone will be famous for fifteen minutes,” provides the lead-in to “The Talent Show,” which collects a series of works that put amateur performers in the role of stars. A woman dying of cancer is captured in sixteen video monitors, while a silent teenager sits nearly still for one of Warhol’s screen tests. There is beauty here, but also a rawness that will make you want to leave the room. Vanity is overplayed in some pieces, while other works exhibit a delicacy of perception that is startlingly quiet.

In Amie Segal’s video “My Way 1,” a series of doe-eyed girls sing the breakup song “My Way” (popularized by Frank Sinatra) in their pink, stuffed-animal crowded bedrooms. Gillian Wearing transforms a photograph of one hopeful model, Dominik, into an airbrushed exaggeration of what he might wish to look like. Dominik’s skin is flawless, but the shining spheres of sweat descending his bare abdomen are too much. His image becomes comic, garish.

Warhol’s “Screen Test: Robin” depicts a young woman who seems to be learning how to be looked at. At first, she’s motionless, hardly blinking, but as the four-minute film progresses, she begins to cock her head, and at once point, she nearly smiles. As for the audience, we have to relax into the role of voyeur. This takes some time, for our subject is, at first, uncomfortable being looked at, and so too are we.

Spanning from 1964-2010, the media range from paper sketches — Stanley Broun’s map drawn by a passerby — to vinyl text on the wall. Carey Young’s “Disclaimer,” begins “There is no reality independent of subjective bias, but there is a reality that is influenced by it.”

The most silent work might be an empty terrine, Chris Burden’s “Disappearing” (1971). Its placard reads: “I disappeared for three days without prior notice to anyone.” The action was taken with no advance announcement and remains un-described, but retroactively has been declared a performance. What the artist did is of no importance; that it was done secretly is.

Hannah Wilke’s document of her own sickness and death, “The Intra-Venus Tapes” (1990-1993), is a 16-channel video piece with footage from the last three years of her life. We see her bathing, talking on the phone, moving into and out of hospitals and bandages: into and out of pain and pleasure and despair. Wilke has long dark hair in one screen; her hair is shorn in another. She has generous hips in one frame; in another, those too, have shrunken. Her conversations overlap into snippets of feeling, while the real narrative is visual. This piece is difficult to watch because we know we are witnessing a genuine march towards death. We know the artist knows this, as she records the act of living with her deteriorating body.

Sophie Calle became famous for an act that many, on it’s face, would call perverse, following a man whose address book she happened to find. Here, the work is twice removed, as “The Address Book” depicts printed interviews with those who are named in the book, not with the man himself, who is never encountered.

This show also includes two interactive pieces that invite viewers to become the focus of the works themselves. Even an empty corner of the gallery seems to invite a verboten photo-op. Maybe we have become too used too performing for the camera, but these early performance-based works offer a look at the underpinnings with both welcome and unwelcome, and always nervy, artistic invasions of privacy.