Continuing through September 25, 2011

National pride can be flown on a flag, sung in an anthem or erected in a monument. When it can be evoked through painting, artists are free to celebrate not just their nation’s triumphs, but its flaws as well. “Modern Mexican Painting” spans 40 important years in Mexico’s post-revolution art renaissance - 1910 to 1950 - all the while depicting a country emerging from Spain’s stranglehold, confronting societal issues and embracing its multifaceted heritage to re-envision a national identity.

The exhibition, consisting of 80 paintings from the 8,000-piece strong cache of collector Andres Blaisten, is smartly organized into seven themes that include modernism, portraiture, surrealism and social critique. There’s a clear message that this is no jingoistic display. And even though the so called Los Tres Grandes, or Big Three of Diego Rivera, Jose Clemente Orozco and David Alfaro Siqueiros, are represented, it’s the free expression of pride, defiance, humility, alienation and other emotions in works by lesser-known artists that leaves the lasting impression.

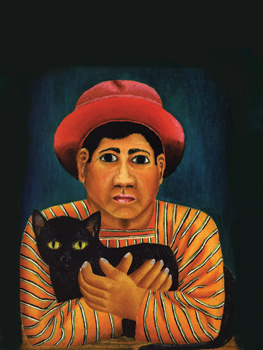

The portrait section probably best reveals the new Mexico. “Autorretrato (Self-Portrait)” (1941) by Feliciano Pena mimics the three-quarter pose and distant gaze of Renaissance portraiture, yet overrides that style with an emphasis on his dark facial features and on a pre-Columbian amulet that he grasps. The image of a lesser-known artist, Emilio Baz Viaud (“Self-Portrait with Blue Shirt,” 1941), brims with confidence as he braces his arms with rolled-up sleeves on a table, an artist’s tool in one hand. The vibrantly colored and noble “El Gato Negro” (1929) by Fernando Castillo balances the intense black eyes of a peasant boy wearing a red hat against the all-knowing green eyes of the black cat that he caresses. On the other end of the spectrum is Siqueiros’ “Nora Beteta” (1948), depicting a seated blond child seemingly intimidated by the formal portrait of which she is the subject.

Surrealism - closely associated with Mexican modernist painting - is represented in several works, including “Dream” (1940) by Carlos Orozco Romero, in which the disembodied heads and other eerie elements of the painting are out of proportion with each other. From avant-garde works to still lifes, the range of the exhibition is such that it also provokes reflection on poverty, indignity and the bleakness of urban life.

The exhibition celebrates Mexico’s rural and agricultural roots. The mural sized “Market/Mercado” (circa 1938) by Alfonso X. Pena fills every space with proud merchants and their splendid wares. Several works celebrate the female form, often featuring dark beauties with flowing hair. Focusing on a different sort of beauty is “Mancacoyota” (1930) by Alfredo Ramos Martinez, in which an indigenous woman seems to lock eyes with the viewer. Meanwhile, there’s a reference to the Mexican flag through the red and green flowers on the cactus in the background.

Even though the idea of a painter being of the people and for the people is attributed to Rivera and his great murals, the varied collection here makes it clear that many other Mexican artists of the post-revolution art renaissance helped amplify that message. The result was the creation of a vibrant national identity.