Moving to Seattle after completing graduate school in Urbana, Illinois, Jack Chevalier made a big splash in New York galleries during the late 1970s and throughout the 1980s, garnering numerous reviews in art magazines and newspapers. He was the subject of one retrospective in 1991 at the Yellowstone Art Center. The Vietnam War veteran, who died at 72 in April, left behind an underappreciated legacy. While it is heartening to trace the artist’s wide range of stylistic developments in this show, it necessarily leaves much unsaid and unexhibited. Based on what we see here, it can be a struggle to piece together why his art developed as it did, i.e., representation to abstraction and back again, or why it was so revered by New York art critics.

Gazing around the entire ground floor of the gallery, we see carved-and-painted wood-and-rice-paper constructions, at first totally abstract but reminiscent of Midwest Plains Indian papooses or saddle bags, complete with paint drips masquerading as sewn beads. These are the works that enchanted those fussy East Coast critics. Was it the pictures’ latent resemblance to indigenous art? Chevalier was not part Native American, but he never commented on possible indigenous links, as did the critics who admired the way ethnic content could be incorporated into abstract art. Chevalier became more attuned to another aspect of his life, the Vietnam War.

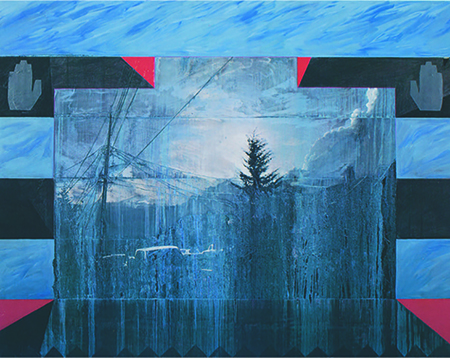

The few early works on view that were shown in New York, “Cross-Eyed Spirit” (1979), “Green House” (1980) and “Jamaican House” (1981), have a compelling intimacy of scale compared to Big-Picture Manhattan. They retained preferred monumentality, expressed through diamond patterns, V-signs, trapezoids, and triangles with faux-feathers attached. The latter work uses the colors of the Jamaican flag — red, yellow, green — to signify the artist’s fascination with Rastafarian culture. Once he moved to remote Vashon Island in the early 1990s, his life attained a greater balance, but the New York presence waned. Wartime demons could be better corralled and sublimated through the increasingly political imagery of his paintings. Gone are the sophisticated abstract paintings Grace Glueck of “The New York Times” attributed to “Indian art of the Northwest Coast,” replaced by a merging of figure and abstract symbol, what Glueck called his “skillful ambiguity.” Chevalier deftly inserted military imagery alongside bright color passages that soaked into the wooden panels, like salmonberries rubbed into a totem pole.

With new imagery, increased size, and an idealized ambiguity that never touched a raw nerve, Chevalier coped with horrible memories, subverting their terrors into ghostly images. The two falling figures in “The Painter 2” (2011) were undoubtedly a prophetic self-portrait. In the decade prior to the figures, irregular-edged wooden panels were perforated to expose space and unpainted areas of bright wood graining. These works, with dazzling optical conceits that never pose as gimmicks, act as protective shield shapes or highly elaborated archery targets. Once again, the heritage subjects are oblique, but never far beneath the surface. The “Ring” series (2001) is well represented; its frontal and nearly symmetrical array of circles recall Tibetan Buddhist or tantric diagrams, levels of erotic “chakra,” or stages of enlightenment.

At their best, the urban imagery of the factories and railroad tracks and the rural imagery of the farm worker, as in the magnificent “The Sower” (2009), express a deep sadness and unfulfilled, nighttime longing. They are beautiful achievements, more powerful than the tiny portrait of “General Sherman” (2014), or the misbegotten fan-mail portraits of Silent Era film stars Louise Brooks and Colleen Moore, sentimental detours into pop culture. Similarly, in his declining final decade, Chevalier’s earnest political views led him into dangerously kitsch territory, such as his series (not on view) of Seattle-area TV news anchors. With the New York acclaim behind him, the serenity arising from house remodeling and Arts and Crafts furniture collecting helped Chevalier cope with unpleasant memories as best he could. Included in the definitive 1989 touring show, “A Different War: Vietnam in Art,” Chevalier received recognition beyond both New York critics, who cooled on the figurative work, and Seattle critics, who continued to admire and follow his art regardless of its occasional aesthetic hiccups.