Continuing through January 21, 2023

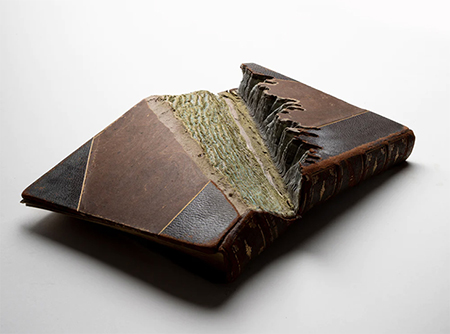

Educated in anthropology and art in Montréal, Guy Laramée is a pioneer of the the book as a sculptural medium. He cuts, carves, paints, and otherwise modifies published and bound books into trompe-l’oeil landscapes and ravines. The first part of this exhibition, “Quebrada,” is a series of nine altered books (mostly in Portuguese) that relate to his recent trip to Brazil where the second body of work, “13 Views on a Stay in Brasil,” was painted. Taken together, the artist conveys in two and three dimensions the radical alterations of real geographic sites within the Amazon rainforest and throughout the rest of that enormous country. While the sculptures are powerful, they contain no surprises: Laramée’s skill and cleverness are as evident as ever. The paintings offer a new aspect of the artist’s talent, so deftly and ominously do they capture the skies and waters of Brazil.

One would not necessarily conclude from seeing the book-sculptures and the landscape paintings that their subjects are endangered environmental targets. Nor do the artist’s two extensive written statements, outpouring of outrage and defense, help much in understanding the unusually creative and innovative objects themselves. In those statements Laramée sounds lofty and technical while mixing in spiritual and religious content, childhood memories and confusing questions such as “Would this change anything in relation to the domination of analytical knowledge over intuitive knowledge?”

Leaving aside aimless Gallic profundities the miniature scale of the book-landscapes is enchanting: valleys, gulleys, and clear-cut forests are discernible without the artist’s written “travel guide.” The relation between the book title and the artistic interventions gradually reveals itself, as in “Balzac Quebrado Book,“ which takes a story by the 19th-century French novelist covered in swirling ink and cuts it open to suggest a river, perhaps the Seine on its way to Paris, as the inevitable destination for so many of Balzac’s rural protagonists. In Portuguese, as the artist explains, “Quebrada has a double meaning. Literally, it means ‘broken,’ but it is also used to designate a ravine.”

“Ciropedia” posits an Amazon natural resource, a stone quarry, gouging out the book’s interior. “Nova Floresta” proposes a “new forest” as a clear-cut, de-forested and gutted gulley. With each attacked, denuded volume of purported knowledge, we are reminded of how greenhouse emissions have been mediated for so long by the Amazon forest, which has been diminishing rapidly thanks to clearcutting. “Lost Paradis …“ alludes to the popular Arthur Conan Doyle novel, “The Lost World” (1912), wherein the characters descend deeply into a jungle only to uncover prehistoric animals. Laramée cuts deeply into the book so as to emulate the depth of the explorers’ paths into dangerous territory. Other works toy with tree bark, imaginary volcanoes, and actions that occasionally sever the book’s binding, thus sundering the object in two. Laramée’s new objects continue to speak to climate change and environmental damage with no need for overbearing declarations.

The 15 paintings about Brazil are quite small, averaging one by two feet. A few have standing figures, but most concentrate on looming skies and clouds, impending rainstorms, dramatic sunrises and sunsets. With such lush scenes and delicate brushwork, they present themselves as beautiful, desirable landscape scenes, distantly comparable to 19th-century Romanticism of Frederic Church, who traveled to the Andes to paint volcanoes and mountain scenes. Eschewing Church’s imperial grandeur, Laramée focuses on particular moments of the day, e.g., “At Dawn,” “By the End of the Day,” and “Protected by the Night.” Sticking to the same size and format — foreground, land, and horizon — the Canadian artist brings a heightened sensitivity to the dangers surrounding such natural beauty, reinforcing contrasts of dark and light not just to provide visual variety, but to portend coming natural disaster.

“Traveling between Two Dreams” lays bare a beach beneath the darkest of clouds. “The Wall” and “The Moon” locate sites in the sky to meditate upon the passage of time. Such intense vignettes of a threatening nature and topography beg to be compared to the greatest poet of endangered nature, photographer Ansel Adams. Laramée evacuates Adams’ inviting grandeur. Humans are reduced to vulnerable status, as in “Coming Back?”, which works either as a self-portrait or view of a refugee awaiting a rowboat to take him away from it all.