Continuing through November 4, 2023

Born in Houston to a Pakistani father and an Indian mother, Ruhee Maknojia says that she lives “on the hyphen.” She identifies as Pakistani-American, Indian-American, Muslim-American, and Texan-American, which gives her a unique perspective, one she uses to “engender civil discourse and discussion.”

Most of her elaborately patterned paintings are based on fables that Maknojia heard as a child, stories handed down through the ages that use gods, animals, or legendary creatures such as genii to convey morality tales. These sprang from a desire to make sense of the world at a time when she was feeling overwhelmed by senseless acts of violence and various wars, such as those in Syria, Afghanistan, Iraq, and Africa. In a YouTube interview in late 2019, Maknojia said that she wanted to use art as a kind of therapy, a way to start a conversation about the issues that were bothering her.

Maknojia settled on the concept of the garden in Persian philosophy as a central theme in her work. The garden is a metaphor for paradise on Earth; everything on the inside is ordered, harmonious, and protected with shade, running water, and fragrance. The garden is a place of reflection and contemplation, peace, and beauty. The outside world, on the other hand, is chaotic and wretched, the manifestation of dysfunction and disorder.

About five years ago, Maknojia began creating installations based on the idea of manufacturing a garden. She had fallen in love with Mughal gardens in particular, where the inside is beautifully manicured. For this exhibition, she constructed a small room in the gallery she calls “Manufactured Paradise.” Open on one end, it was fabricated with a combination of paint on canvas, Banarasi silk fabric, and artificial grass. In this way, she introduces visitors to some of the raw materials that inspire her paintings.

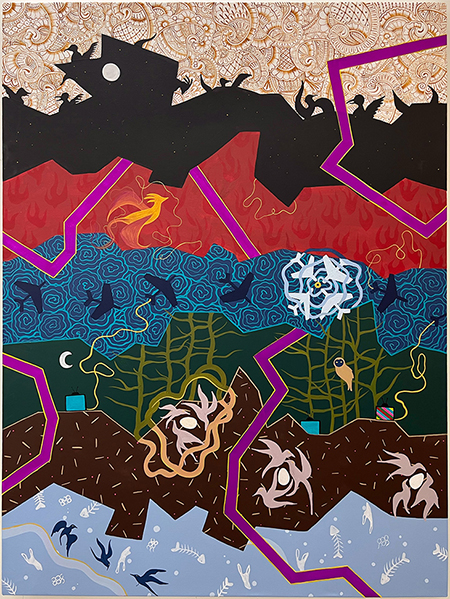

In her paintings, Maknojia uses the fables as a way to question ethics, values, and power structures. Conversely, they serve to convey her concern regarding the environment, and seek the truth in an ever-growing and interconnected world. They convey wisdom that transcends cultural and geographical origins. The intricate patterns in her paintings pay homage to a rich heritage based in textiles, rugs, mosaics, and decorative objects. She has developed a lexicon of patterns to express certain concepts without being literal. For example, an arabesque pattern of green stems with red flowers on a blue ground represents water; an elaborate yellow and green leaf pattern represents land; and concentric circles of dark blue on a light blue background signify the sky.

These patterns and a few more appear in “Kalila and Dimna,” a tale of two jackals living in the kingdom of the lion. As disruptive elements, they start a rumor that the lion’s best friend, the ox, is trying to destroy him. This leads to a fight in which the ox dies. Maknojia brings this fable into contemporary culture to comment on how gossip and misinformation travel faster than a plane or even an astronaut in space, both of which appear in the painting. She also includes a paisley pattern. For Maknojia, the paisley, a leaflike form thought to have originated in central and south-central Asia, is the embodiment of nature, repeating endlessly to infinity. Paisley-printed and woven textiles were traded along the Silk Road. The pattern eventually became part of many cultures, much like fables, fairy tales, and myths.

An impressive eight-minute animated video titled “Paisley’s Odyssey” is projected on the end wall of the gallery. Although Maknojia has been experimenting with animation for a while, this is the first time she has shown one publicly. “The paisley travels endlessly through different parts of the world,” the artist said in a discussion at the gallery. “The paisley was never born, it just exists. Everyone wanted a piece of the paisley.”

“Creature in the Dark” was inspired by a poem by Rumi, the 13th-century Persian poet whose influence continues today. “The Blind Men and the Elephant” is about a group of blind men who have never seen an elephant and are placed in a room with the creature. After touching different parts of the animal, they describe it variously as a column (the trunk), a sword (the tusk), a throne (the back), etc. They bicker as to who is correct, a metaphor for people who do not attempt to understand different points of view or form conclusions without all the facts.

Maknojia adds a thick purple line that connects her larger paintings. It angles along the wall, wandering in and out of four paintings so as to connect them. She refers to it as a “through line” or a “thread,” conveying her belief that even though the stories she illustrates are from different writers, centuries, and empires, they are still relevant today. Maknojia uses her patterns as a universal language to “make visible intricate historical constructs that are embedded in contemporary life” and encourage the exchange of ideas and understanding among diverse people and communities.

In the mid-1970s, a group of mostly American artists working with patterns, grids, and textiles came to be known as the Pattern and Decoration movement. They reinterpreted modernism by embracing ornamentation and beauty, which was regarded as a reaction against the patriarchal traditions of Western art, which they thought embodied sexist and racist assumptions. Inspired by Islamic tile work, Byzantine mosaics, and Iranian and Indian carpets, as well as wallpapers, printed fabrics, and quilts, these artists were interested in blurring the line between fine arts and crafts. Whereas craft was associated with the feminine, the fine arts were mostly masculine. Maknojia is part of a resurgence of interest in using patterns in works of art. Multiculturalism, identity issues, social media, and non-Western ideologies and cosmologies all play a role in this movement.

Maknojia has embraced these decorative elements as a vehicle to create an ideal space where her characters can interact, and her patterns become active participants in the storytelling process. Drawing on her rich heritage, she adopts these visual concepts to balance the esoteric and the exoteric, the spiritual and the worldly. The metaphor of the garden serves as a vehicle for her ongoing investigation of the tension that exists between these inner and outer spaces.